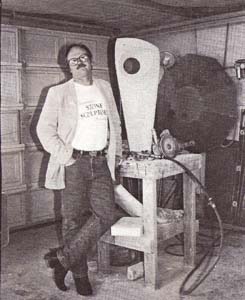

The following is an interview with sculptor Reg Akright. Reg has been a NWSSA member since '91 and has been a contributor to the Sculpture Northwest newsletter. He currently serves on the Board of Directors of the Art Council of Snohomish County. He has worked at various heavy construction jobs including bridge ironworker, bronze foundry chaser, and miner. He works a full-time day job as a repair technician for a hot tub company. 1 visited him at his home and studio in Everett, Washington. The small home is full of art .(his and others including paintings by his father), a welded dining table and other metal art furniture by Reg. We then headed toward the backyard studio. Reg showed me his outdoor work areaa welded, awning-covered, "A" frame designed to support an "I" beam and track-mounted 3-ton chain hoist. Within this structure, a 5'x2' slab of granite awaits its first cuts. Next to this is his "cozy" indoor studio which is set up for pneumatic carving and steel fabrication and is warmed by a wood heater.

RA: I have a strong sense that I want to work with stone that's locally available. I really like the local granite, the cascade granite. It's cheap, it's a good stone to work, it's a part of our local environment and I like that. I like native Washington stones, though I'm not drawn to sandstone. With granite, it's so cheap I can play with it. If I screw up or break a piece, it can become "yard art". I'm not out much except my labor. In contrast, I have a beautiful piece of Portuguese marble in the studio that I'm anxious to work, but I don't have a refined idea yet, and I don't want to start 'til I'm certain of the way I want to go with it because it's such a rare piece of stone. I don't want to do the "wrong" thing with it.

SS: With the granite, are you more likely to just dive in?

RA: I have a pretty good idea where I'm going to begin in granite and I'm not afraid to just dive in. If I have a good idea about the piece, even if I haven't sketched it, I feel comfortable just diving in. I sketch on the stone or do rough sketches. But with the granite I rarely do a maquette. I have a pretty good mental picture of where I'm headed. I'll work out specific details on paper sometimes.

SS: You seem to primarily work with abstract or non-figurative forms. Why is that?

RA: I don't feel drawn to doing realistic work. I used to be an art-school elitist, but I don't feel that way any more. I've come to respect realistic work. Carol Way and Maarten Schaddelee use elements of realism in a way that I really like. I like it for what it is. I'd love to have some of Tracy Powell's work in my house. Rich Hestekind is a strong source of inspiration for me. When I first came to NWSSA meetings, he showed me a picture of a sandstone piece he'd done. The piece spoke very strongly to me. His formal vocabulary was such that it was yelling at me. It was seriously communicating. That was the inspiration to start carving again.

My source of inspiration, my pieces, are more a meditation on shape and line and form. I like gentle lines, subtle curves as opposed to sudden sharp curves. I like a smooth flow to something that makes a quiet statement of its own. I've tried to think of a formal justification for what my pieces are and why they are, but I don't have one. I just do what pleases me. I want something that's quiet and makes a statement and becomes part of wherever it is. Something that alters the space in a pleasant way. I want my pieces to affect space, not dominate or control it. I'm not out to make a social message or statement.

SS: What do you see as the importance of art? How does it function?

RA: (sigh) Try to imagine a world without art. Without great painting, sculpture, without a sculptural sense, the world would be au awful place, a dreary place. Art infuses every level of our lives. I view art as aualogous to pure research science, which has little point other thau to "find out". That's what art is, "finding out". From there it filters into society through design, into functional objects. Also, just to have art around, like large sculpture, is au expression that we're doing it because we can. They're expressions of the joy of being alive, being humau aud being able to produce a fine work of art.

SS: In your work it seems like you've settled into a path of sorts. You seem to have types of forms that you are developing.

RA: I've accepted the family of forms that has come to me. I've begun to identify "Reg" shapes. I don't fight that auy longer. I see the continuity in the work of other artists, similar forms. I like and respect Uchida a great deal. In his work, his formal vocabulary is one which speaks volumes to me. His work is similar to what I aspire to. He uses spare lines, not a lot of texture. I waut to integrate more natural surface in with somewhat fiuished surfaces, aud so on.

SS: Why is that? Why are you drawn to certain forms? Why are certain forms more compelling?

RA: There's something about strong simple forms that has always struck me. While working heavy coustruction on highway projects in Wyoming, I loved looking at long stretches of unmarked concrete, bridges that were completed, but without road approaches yet, standing alone. They were like huge pieces of sculpture standing in the Wyoming sky. The process of seeing those coustructious come together was almost a mystical sculptural- type experience. I've always loved those clean simple shapes. Then being on WWU campus in Bellingham, Washington (where he attended and graduated in sculpure '78-'79) and being around their contemporary sculpture collection (which includes work by major contemporary sculptors such as di Suvero, Caro, Nognchi, Serra, Morris, Holt), influenced me a lot. I always loved looking at sculptors who used strong, simple forms: Henry Moore and Braucusi, the classic moderuists. I've seen lots of art from different areas aud the work that has always drawn me is work that uses few lines to say a lot.

SS: Out of the possibilities which occur to you, how do you decide what to do?

RA: I gness it's au editing process. I have to trust that what I decide to do is going to be right. I don't know how spiritual a person I am - I sometimes think not very. And other times I think I have some sort of real strong, unexplained, spiritual connection. One thing I'm learuing over time is just to trust. Not to think things out too much, when I'm trying to decide how to go with a piece. It's that sudden impulse to do something. Before I know it, the tool's in my hand and I'm just doing it. You have to trust your artistic instinct. I could over-rationalize a piece aud kill the piece that way. Sometimes I just have to start. I've got a rough idea of what to do. I'll sketch and sketch, bnt I can't quite laud the idea, exactly what it is. But, I've got to start! I just start and it works itself out. Not every piece is going to be the best so you have to accept a mistake here and there as far as the learning process. You also have to learn to trust. If you make a mistake, you make a mistake. You're better to risk creating a piece that's not everything you think it could be, then over-aualyzing aud not creating anything.

With Cascade Monolith #1 (seen at the flower and garden show and subsequently sold to the 9th District Circuit Court of Appeals, Pasadena, Califoruia.) I had a pretty good idea of what I wanted to do with that piece when I started. But the opeuing in that, which turned out to be a square window, I hadn't conceived of. Originally I thought of a round opeuing, but couldn't figure out how to do it. I started working on the piece aud it just came to me, "this is how I do it". It turned out to be one of my favorite pieces because there was an element of surprise in it. Stonecarving is a slow enough process that you have time to think about it as you go.

SS: How do the rational and the intuitive elements work together for you?

RA: The initiative comes as the sudden flashes of insight. The ah-ha, the bolt out of the blue that says "this is how you do it." The rational part comes with thinking the process through - in the mundane parts of the process like gelling a good flat base, or looking at a line and deciding what bothers me abont it, what I need to change. The intuitive is the sudden flash of insight that's the heart of the piece. The rational is about "how" to make that intuitive flash work a bit better.

SS: Do you feel a sense of control over both processes?

RA: I don't know how to kick the intuitive into gear. It just comes to me at various times.

SS: How do you balance your day job with studio time?

RA: I like to get 10-15 hours per week in the studio. That is sometimes difficult to achieve with the demands of my day job. When I'm involved in a project, I'll set it up in the studio where I can work on it for whatever time I have available.

SS: How much work do you produce in a year?

RA: My goal is to get at least ten pieces out per year. I want this to be more and more a part of my living. The studio did earn a full quarter of my income last year. And the studio paid for itself.

(We then toured his yard stopping to view "Oolitic Apollo" a large Utah limestone piece atop a structure made of welded steel plate, painted red)

SS: One of the things you've got going here is the use of fabricated metal elements or bases. What is your thinking about these? Do you see the "base" and the stone form as one composition?

RA: I did "Organic Nike" and "Oolitic Apollo", (both contain limestone carvings aud welded metal elements painted red) one after the other. They were very important pieces for me. I was truly happy with what they accomplished. That's been controversial for others, about how well that works. I am working towards a piece that cau be viewed as a single integral piece, with metal and stone working together to create the piece. That's how I view this piece although the trausition between the metal elements aud the stone isn't as seamless as I would like. But, that's the artistic process, you don't know until you try. Each step brings me a little closer (to finding the best solution). I view art as experimentaL It's trying something new, going in a new direction, trying new combinations.

(We move into the studio and view Cascade Monolith #3 a cascade granite piece close to completion, on its w~ to be displayed at Gallery Mack, Seattle)

RA: This is a piece which took its own course. It was one of those pieces in which the energy didn't feel "right on". So I set it aside and completed several other sculptures. Finally, I saw the solution to what had troubled me about the piece and was able to complete it. It will have a "nine point" texture over the whole piece. I like that texture on this granite. Cascade granite is such a strong stone unpolished, rough, showing the strength of the stone. (I don't think it comes off well polished.). For the most part I like stones that are monolithic in character without much variation in color. The color tends to complicate a simple form.

SS: How do you decide about scale?

RA: I can have a general idea then go looking for the stone and adjust the scale accordingly when I find the stone. Or I can go rummage through the end cut pile at Marenakos stone yard aud find a piece I want to work with. I like a scale that is close to body size. Not so large that it becomes monumental. But not so small that it becomes an object.

SS: I'll close this interview with a quote from Reg's artist's statement:

"I love the processes involved in creating my sculptures. The noise and dust and resistance of the material involved in the stone-sculpting process, and the heat, smoke, spatter, and flame of the welding process, all satisfy an almost primal urge. From these violent processes are born pieces which, I hope, have a strong, yet serene, almost meditative presence. In that way I am able to integrate my intellectual/artistic side with my hard-laboring industrial history. Art is the glue that bonds and makes sense of my life."

Thanks, Reg.