When visiting relatives in Iceland after Camp Brotherhood last summer, I was still so caught up in the spirit of our sculpting symposium that I decided to learn about stone carving in this geologically-young land that sits astride the mid-Atlantic ridge. I started with queries of my cousin Gretar and his wife who live in Hafnarfjoerdur within greater Reykjavik (along with over 40% of the nation's total population of 280,000). As they are interested in the arts and share in their country's pride in its achievements, I soon had some excellent leads-to stone sculptors they knew or had heard about and to museums. Here, in brief, is what I learned.

Norse Vikings, who began settling Iceland in the 800s, found a volcanic land with forests in the valleys of the older eastern and northern sides, interior glaciers that reached the coast in the southeast, fresh lava flows in the south and southwest, and many fjords in the northwest. The larger forests soon fell to their axes, so their descendants relied on driftwood, sod, and stone for construction. With the rise of fixed settlements and the coming of Christianity (around 1000), stone masons started shaping the island's basalts, rhyolites, andesites, and rare gabbros for thresholds, fonts, and monuments that their patrons hoped would endure for the ages. The Danes, who took Iceland from the Norwegians around 1260, slowly-very slowly -encouraged, or at least tolerated, the entry of its residents into the increasingly dynamic European economy and culture.

A tardy example of this trend was the pioneering sculptor Einar Jonsson (1874-1954). Raised in Iceland, he learned sculpting at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen and began exhibiting there in 1901. His rise within the European sculpting scene attracted so much attention back in Iceland that in 1914 the local parliament agreed to provide him with a studio/home/gallery on a prominent hill on what were then the outskirts of Reykjavik. He came back to Iceland in 1920 and moved into his grand atelier three years later. Jonsson's main sculpting medium was plaster. He also carved in wood and arranged the casting of a few bronzes. While some of his designs would have worked nicely in stone, he chose to avoid our difficult medium. Nonetheless, he had an abiding interest in his homeland's basalt as is attested by his frequent use of columnar motifs in his pieces.

Iceland's first sculptor to do a substantial amount of work in stone was Sigurjon Olafsson (1908-82). Also trained in the Royal Danish Academy, he started with plaster and went on to sculpt in many other media as well during his long career. In Denmark he did seven stone carvings between 1935 and 1944, including a pair of monumental granites-one with figures representing agriculture and handicraft, the other with figures for industry and commerce-that were commissioned for Vejle's town square. Olafsson returned to Iceland immediately after World War II. Happy to be back in his rocky homeland, he sculpted many pieces in stone-usually local dolerite and gabbro, but also imported granite and marble-until lung problems forced him to forsake this medium in the mid-1950s. His earlier works had ranged from realistic busts through stylized representations to abstract shapes. During this, his main stone-carving decade, he primarily added to his corpus of stylized human forms. One of my favorites is his lanky yet graceful "Woman Bathing" (see photograph). A large collection of his work is now displayed in and around the Sigurjon Olafsson Sculpture Museum, which his widow established at their studio/home on Reykjavik's spectacular north-facing shore.

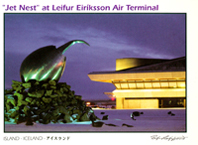

Reykjavik's increasing prosperity and size in the postwar decades engendered ever more attention to the visual arts. Sculptors working in all media began putting on outdoor exhibitions in the mid-1960s and founded the Reykjavik Association of Sculptors (RAS) in 1972. Its 14 initial members included the metal sculptor Magnus Tomasson, who seems to have been the only one who frequently incorporated stone in his work. His "The Jet Nest"-a big stainless-steel egg hatching a jet in a lava-chunk nest-sits just outside Iceland's international airport (see photograph). By the year 2000, the association's membership had risen to nearly 100.

Thanks to Gretar, I met three RAS members in stone carving during my visit to Iceland. The first was his former teacher Gestur Thorgrimsson (b. 1920), who had recently been incapacitated by strokes. He and his wife, the ceramicist Sigrun (Runa) Gudjonsdottir, met at Reykjavik's new School of Arts and Crafts toward the end of the war. Soon marrying, they studied for a year at the Royal Danish Academy where Gestur focused on clay sculpting but privately started working with wood, bronze, and stone. Returning to Iceland, the couple earned their living over the next four decades mainly from the teaching of art and the sale of hand-painted pottery. Gestur was, meanwhile, intermittently pursuing his interest in sculpture. Upon retiring in 1985, he devoted himself ardently to sculpting with wood, metal, and especially stone (marble, rhyolite, basalt, gabbro, and granite) in their home/studio in Hafnarfjoerdur. His largest piece was a commissioned basalt and steel fountain, "Rendezvous of the Elements," beside a nearby stream. Most were smaller stylized or abstract forms. Among them, my favorite-because of its intriguing juxtaposition of granite and steel-is "Off Balance" owned by Iceland's National Gallery (see photograph).

I next met Gretar's classmate Einar MarGudvardarson (b. 1954) at the studio/home that he and his wife, Susanne Christensen, share in a lava field near Hafnarfjoerdur's shore. After initial artistic training and work in film, he learned stone carving in Greece during the late 1980s along with his wife (out of ignorance I must pass over her sculpting career). Since then, he has worked primarily with Icelandic volcanics, Greek red and Belgian black marble, and Bornholm granite. He has carved not only elegant formal bowls (which attracted much attention when exhibited in Japan) and playful garden pieces but also large representational and abstract sculptures. At the time of our visit Einar was preparing for an installation in Reykjavik that would use video projections to "bring several [partly-shaped] granite pieces to life." He encouraged us on our departure to see a piece that he had recently done on commission for a fishing consortium at the harbor. We soon found his fluid portrayal in granite of a fish's tail disappearing beneath a wave (see photograph). As a seasoned fisherman and a novice sculptor, I viewed his achievement with awe.

"Stop!" I yelled to Gretar on a back-road excursion we were making near the end of our stay. We were en route to the studio of Pall Gudmundsson (b. 1959) and on the barren hillside we were descending I had glimpsed evidence-the face of Bach carved on a lava boulder (see photograph)-that our destination neared. After photos and another 20 minutes of driving, we reached Husafell in a green valley between two glacially-rounded volcanic ridges. Pall, who enjoys a reputation as a talented original in Iceland and has pieces in the National Gallery and other public collections, welcomed us to his tower-shaped studio. We learned that (notwithstanding four years at the College of Arts and Crafts) he is an autodidact in sculpture. His materials are lava, rhyolites, and andesites from the surrounding hills. His implements are simple hand tools. His carvings are typically bas-reliefs of faces, often of famous musicians. His fascination with musical motifs is also manifest in his flat-stone keyboards. To our party's delight, my wife Sally was able to play melodies in tune on the studio's stone "marimba."

My impulsive decision to delve into stone sculpting while we were in Iceland enriched the visit for me, my wife, and our hosts. It broadened my view of this remarkable country's history and culture. And it gave me ideas about materials and designs for my own carving.