I have spent over a half-century in schools so far, all of it learning and two-thirds of it teaching. Lately I have been reflecting on my own growth at various stages, particularly on how individual people influenced me along the way. Here I will share with you how Deborah Wilson triggered a significant turning point in my development as a sculptor.

My story has three messages. First, good teachers realize that students must do their own learning and that good students will do it. For the most part they stay out of their students' way, providing instruction only when it is needed. Second, good teachers realize that significant learning requires significant risk on the part of students, that students are conservative about taking chances, and that students sometimes need a swift kick in the butt. Third, great teachers do both with impeccable timing. Deb was great with me.

I met Deb five years ago at Georg Schmerholz's studio, after hearing and reading a lot about her work. I liked her immediately, began to imagine working with her, and I proposed to be her student for a week. Deb was hesitant because of the drain on her carving time, but I had been carving seriously for a decade and needed little instruction. Mainly I wanted to work alongside her and learn what I could about how she worked. After I promised not to demand too much, Deb agreed. I arrived in Vernon on a hot August day in 1992 with my tools and a sculpture that I had been working on for a couple of months. Some of you saw the piece at the 1995 Symposium. It is nearly complete now, after several thousand hours work, but at Deb's it was little more than a piece of thulite.

I kept my promise to demand little of Deb. She stayed out of my way, I carved, and she carved too. We had a great time together, and both of us accomplished a lot. I went there to learn, though, not just to have a good time. But as I said, students tend to avoid risking much. It was a bit of a surprise to learn that in spite of my understanding this as a teacher, I was a typical student in avoiding risk at Deb's. Here is what happened.

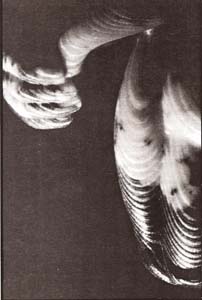

The piece is an abstracted, geometrically transformed human figure. Unlike all of my other pieces, this one has most of its parts. It has parts now, that is. Some of them were emerging then, but some were just rough lumps of rock. In particular, the arms already projected in front of the body, but I had avoided carving or even thinking much about the hands. I couldn't even draw hands, let alone carve them - even Mickey Mouse hands with only three fingers and a thumb. Although I had carved abstractions of hands before, they had had no fingers, no thumbs, no wrinkles, and no fingernails. This piece was no exception. Even though the body and the arms were taking form behind them, I hadn't touched the hands. The piece looked like a lovely woman with a big fuzzy hand muff, and it didn't work. I was in a bind and scared, but hadn't yet realized either of these things.

At one point. Deb asked, gently. "What are you going to do with the hands?" I tried to get out of it, saying. "Oh, I've been thinking I'd carve them holding a bowl of water," or some such excuse. Equally gently, she said. "Chickenshit!" That's all, and that's all it took. What a great teacher!

Telling this story about Deb reminds me of something that happened a couple of years before I met her. My friend UIIi Steltzer said something like, "Lee, your sculptures are all smooth and beautiful. They have no edges. Your life is not smooth like that. Your life has edges, lots of them. Your life has points, too, and it isn't all beautiful. Why don't you carve edges and points, like your life, Lee?" All I could say was that I like smoothness, and I still do. But Ulli's question probed the negative side of my preference. It probed what I avoid, so I carved a piece with edges. When Ulli saw it, she laughed. "OK, you can carve edges, but the edges are smooth. You think the edges of your life are smooth like that?" Ulli is another great teacher.

The most important thing I learned from both of these incidents is to work on what I think are  the worst parts of my sculptures, not the best. More and more, I've been doing that, and it has rewarded me richly. Each day when I enter the studio I spend a few minutes looking for the parts that stand out as least well integrated into the whole; in my street language, I look for the ugliest parts and carve them away.

the worst parts of my sculptures, not the best. More and more, I've been doing that, and it has rewarded me richly. Each day when I enter the studio I spend a few minutes looking for the parts that stand out as least well integrated into the whole; in my street language, I look for the ugliest parts and carve them away.

Thanks, Deb. Thanks, Ulli. (Thanks also to Rich Beyer for introducing me to thulite. It is an incredible, beautiful material to carvehard, strong, and very forgiving.