Stone Queries - May/June 2003

- Details

- Created: Friday, 02 May 2003 04:38

This issue’s column is of a somewhat different character, more overtly philosophical, or opinionated, depending on your viewpoint. Having been trained and employed as a minerals exploration geologist for nearly four decades I tend to become defensive when I encounter, even among stone sculptors, the attitude that mining is an unworthy or unnecessary activity.

This issue’s column is of a somewhat different character, more overtly philosophical, or opinionated, depending on your viewpoint. Having been trained and employed as a minerals exploration geologist for nearly four decades I tend to become defensive when I encounter, even among stone sculptors, the attitude that mining is an unworthy or unnecessary activity.

Recently I was asked to contribute comments to a university panel discussion on environmentalism and the materials used by the design professions: architecture, landscaping, and fine arts. One specific question was whether I lost any sleep knowing that I carved irreplaceable marble extracted from the mountains of Italy. This was my response. No activity, whether building, landscaping, producing art, or breathing, is without environmental consequences. Some consequences are local, some are truly global. Atmospheric effects are global but products and services are now sourced globally as well. Satisfaction or outrage become matters of judgment and opinion, informed or otherwise, and (as in real estate) a matter of location, location, location. Perceiving some practices as environmentally enlightened may be a case of ignoring the necessary nasty bits that take place somewhere else.

Building a structure with coated glass for higher lighting, heating, and cooling efficiencies is admirable but it’s no particular cause for claiming the high moral ground (which is usually overcrowded with remarkably divergent opinions). Behind that double pane window are mines producing silica sand, soda ash, and limestone for the glass itself as well as tin to float it, other metals to coat it, and a cryogenic gas separation plant producing argon to fill it; plus all of the additional resources required for processing and transportation. How high is the price? We are now beginning to recognize the concept of total life cycle costs - in electronic devices, for example. Without such information it is difficult to quantify the actual costs of most of our activities, assuming of course that we can even agree on what is a pertinent cost.

We can reduce the more egregious insults to the environment, but no human society can exist on any level without extractive industries. We can minimize the insults but somewhere there must be a hole dug or a plant felled. This is, literally, a fact of life. I dislike the hypocrisy of not admitting we extract to be able to live, even to be able to protest extraction. I am not unaware that my Italian sculptural stone is nonrenewable, but I lose no more sleep over that fact than I do over the concrete or asphalt pavement in Interstate 5, the mineral fillers in my compact disks, the titanium dioxide whitener in my toothpaste, or the kaolin clay in the paper of this page you are reading.

Life would be different without them, but not necessarily simpler or more environmentally friendly. I can smugly argue that sculptural material is less than 5% of the total marble produced from the Carrara district so I’m not responsible for its rapid depletion. But I also must admit that I couldn’t afford to carve Italian marble without the subsidy provided by the production of the other 95% as architectural stone.

Stone sculptors should be aware more than most that their chosen medium comes from a mine. Some of us quarry it ourselves. Mining and processing are required for our most basic tools, hammer and point, and even more so for our angle grinders and diamond disks. Each of us has to weigh the benefits versus the costs of our carving, as indeed we should for all of our activities. Like all of us, I rationalize.

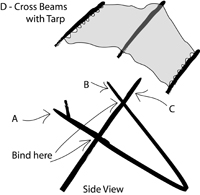

People always come by my worksite at Camp Brotherhood and admire my Wiki-Up, so I thought I would share the construction guidelines. I would really enjoy seeing more creative work sites, so don’t be shy about trying this!

People always come by my worksite at Camp Brotherhood and admire my Wiki-Up, so I thought I would share the construction guidelines. I would really enjoy seeing more creative work sites, so don’t be shy about trying this!