This is an interview with Tamara Buchanan which took place on May 12, 1996 at her studio/home in Kirkland, Washington.

She has been a NWSSA board member since 1994. Over a period of twenty years, she developed the Sweetbriar Wholesale Nursery in Kirkland, which she owns and operates with her husband Doug Benoliel. She recently spent a month carving marble in Carrara, Italy.

We started with a tour of her studio, which consists of an indoor workshop filled with a variety of stones, tools, and her new heavy duty compressor. Tamara was excited about the compressor and all that it could do! In fact, it was important enough to deserve .3 name--she called it Curtis. We hugged it in appreciation! Then we moved on to her carving area outside where we began our conversation with a question about a sculpture in progress.

Steve Sandry:Tell me about your process with this piece.

Tamara Buchanan: I had an idea for a very large sculpture. I was in love with a concept, and I was trying to bring that idea to the stone. But the stone dido't want to be that. I occasionally look at it, touch it, feel it and ask what it wants to be. So far it's being very stubborn, and that's ok.

SS: Has that happened before?

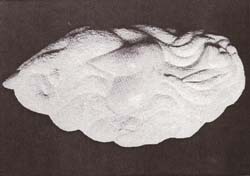

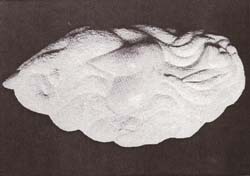

TB: The most magical tinae was one of my first pieces, a piece of translucent Greek Alabaster. I was going to make a bird with outstretched wings, so I could shine light through it--I would have this airy ethereal bird. I was carving away, but the next day, it was screaming at me that it wanted to be something rounded. I went with it. It became the Nautilus piece "Solitude", which really pleases me. I'm allowing myself the tinae and the grace to listen. Doesn't happen frequently, but those times are magic!

SS: Do you ever use a more rational planning and executing process?

TB: With the large linaestone figure it was close to that process. I started whacking away and realized I should decide what I wanted to do here. So, .I went back, got photos to work from and did a couple of models Although, I'm not a truly planning type person, the inspiration came from a lovely art photograph.

SS: How did you feel about that process?

TB: I feel ok with it. I do fmd I lose some spontaneity working with a model. It's fun when the flow is happeuing. That's great!

My first experience with carving was at the first symposium in 1987. George Pratt was there and got me started on a piece of limestone. And Lee Gass gave me a piece of Mexican onyx which was my first hard stone. He started me on his diamond tools. So, I skipped the business of soapstone. I like something I can hit and it won't shatter. Granite and marble are marvelous stones for me. get joy from both of them.

SS: What is it about the resistance the harder stones give you that is appealing?

TB: The Italians call marble "bones of the earth". It feels grounded, solid, earthy. They are not so brittle or tender that they would shatter if hit the wrong way. It disturbs me to be working with alabaster and be so coucerned with bruising it.

I find I'm carving faster. I started pushing in that direction last summer--not worrying or stewing so much, but letting energies come through. I used that approach in Italy. I had just a month to work there and wanted to get as much started as I could. I was roughing out about a piece and a half per week. That felt really good--to think and work, but also to not think and work. To let the stoue, tools and my hands have communication-- that's where I think I'm headed. I worked daily 8:00 to 5:00, and found I could physically do it. I learned a lot about myself: what I can handle, what I can do. I learned patience aud trust.

SS: What was the studio like in Italy?

TB: It was a pop and son type operation-- mostly custom work or reproductions of their own models. It was small, intimate. It's mostly a teaching studio now. They move stone with pry bar and roller. Most of the carving is done with air tools.

SS: How did the student-teacher relationship work?

TB: It was Silvereo's studio. He was there to give whatever instruction I wanted. Most of the tinae he would ask if I needed help. A few tinaes he insisted I learn to sharpen tools.

SS: Why did you go sculpt in Italy?

TB: I knew that I had to go. I wasn't sure why. In retrospect it was to learn patience and to learn to trust in my work with stone and also in geueral in my life. Perhaps I may have found my next mentor: an elderly sculptor, Enzo Pasquinni. I felt he wanted to share his knowledge aud expertise. I'd like to go back in 1997 to work in his studio. I think there are some things he can teach me about art, stone, and maybe about life.

I think mentors are very important. That's another good thing about the Association. It can provide access to mentors that you can't fmd in the studio by yourself. George Pratt has always been my mentor along the way. I missed hina at the last symposium, for my yearly "how am I doing, George?"

I discovered while working in Italy that many of the artists, famous Of unknown, come there for some of the same reasons we go to the Symposium. Italy was the only place they could go to fmd the comradery and support, both technical and emotional. There was a man from Vancouver Island, B.C. who didn't know there was a support system available to him locally. Sometimes we don't realize we have something so special.

SS: How did you know to enter a mentaring process?

TB: Because it was available. And I so badly wanted to sculpt. I knew that this is what I should be doing. I came into it at a time when I was facing my own mortality from a cancer scare. I'd also had some losses of siguificant people in my life aud my dog of nineteen years who was like my son. Many things, all at once, came crashing down. What I turned to was the stone. It is very grounding. I love being dusty; I love to touch the stone-smooth, rough, chisel marks, all of it.

I have a very stable life now. I have someone in Doug who believes in me and accepts me for the prickly person I can be sometimes. He's been incredibly supportive. It's taken major setbacks in my physical and emotional health for me to realize "I can try this". And then I stumbled into The Artist's Way by Julia Cammeron. Very synchronous. I don't think it was meant to happen sooner. Maybe I had to go through the garbage fIrst.

SS: It souuds like things are coming together for you.

TB: I am so blessed. I have a peace now that I've never felt. Doug has encouraged me to take my time and not worry about selling. Enjoy doing the art; when the time, comes it will sell.

SS: As a woman, do you see your approach to art as unique?

TB: I don't personally feel my approach to art is any different because of my sex; but it may have been seen differently because of my sex. When I started working with granite, the guys would go off to talk granite, and I would be excluded. That still happens. It's hard to be taken seriously if you dou't create more than three or four pieces a year, but that's not a gender thing.

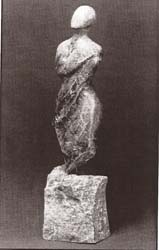

SS: (We view her most recent piece "A Simple Twist" situated in an adjacent garden. It is her first completed piece from her Italian adveuture.) How is this piece different for you?

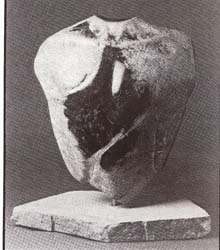

TB: This piece represeuts a shift for me. It's simple in content, nothing fussy about it, and it's not representational. I enjoyed playing with it. It's a movement of lines and contrasts. What I fmd lately is that I can't finish anything. "A Simple Twist" was finished and then not finished. I found that during final polishing, part of me wanted to take the piece further, cut in there deeper, etc. So, it never ends. The limestone piece "Emerging" is a large bud shape with two petals in a semi-open position around the bud. I really want to change that piece. It's technically finished, but I had a vision that the cone is supposed to be a face, pointing upward. I can't wait to recarve it.

SS: So, you have a way of staying in process with your pieces?

TB: This is new for me. I am trusting that it can be fmished or not finished and be ok. The process can continue. Not rushing, having patience. Before I had an orientation of haviug to finish and getting it sold, which was self-imposed. That's changed.

SS: What was your early experience with art?

TB: Here's a drawing story: I was asked to leave the department at WWSU because I didn't have any talent: so much for beiug an art major. The Artist's Way helped me out of that horror story.

I did have a wonderful high school sculpture instructor, John Pilikowsky. I got a lot of encouragement and felt some success in his class. He handed me a rock at the end of school and said "I think you can do something with this. ". I took it home and thought about that rock for the next twenty years. At that point I found out about the 1987 Symposium, which was the first one. I've been to all the Symposia since, and still playiug with rocks.

SS: When did you become a board member? And how has that been for you?

TB: The first time was 1994. I felt I had skills that could be used by the Association. It's a lot of work, time and emotioual commitment. I also appreciate getting to know the Board members.

It's fun to watch the Association grow and change. Having been on other major boards of directors, I have strong feelings about what the Board is supposed to be doing. Our job is to manage the business of the Association. We now use a budget, we have an accountant, we have a way of managing the records, and we've obtained non-profit status. Now we can proceed with a project--like creating a sculpture center. We're getting art more and more sophisticated.

NWSSA is really driven by its members. It's important for the membership to understand and remember that. Membership comments and input is what moves the Board in a direction. We welcome hearing about the concerns of the membership.

One new project I'm interested in is the possible development of a sculpture center at the former Sandpoint Naval Airstation. It will need energy and talent to develop, and we've got it. For instance, we'll need help grant writing and fund raising.

SS: What do you mean by "pushing the stoue"?

TB: It goes back to "when are you finished?" .... wanting to express more feeling and depth.

For instance, you guide and move the light to convey emotion. I have always worked with lights, darks and shadows. Now I want to work with lights and lights! Allowing light to come through a piece, not just through the stone itself, but through some piercings in the stone. Also, you polish different parts to differeut levels. The light hits the various areas in differeut ways and you're able to control how the eye moves over the piece. The light and the stone together are the sculpture.

SS: Are you selling pieces?

TB: I sell at our nursery to landscape architects and contractors. I sold eight or nine small works at the open house show. I believe in George Pratt's approach. You start people out as collectors by selling small "coffee table pieces". Then they're your collector. They're more confident, and they start buying more important works. That's happening for me.

SS: What is your advice for other artists?

TB: Read The Artist's Way. Surround yourself with people as supportive as my husband. Keep a sense of humor. Have fun!

This is an interview with sculptor Tracy Powell, which took place at his studio in Anacortes, WA on March 5, 1996. Tracy has been a NWSSA member since 1992 and an active carver since 1980. He recently was elected to the Association's board and will be a carving instructor at the summer symposium. He contributes in many ways as a kind, joyous and supportive person, and by example, as an active creator. His stone sculpture is currently being shown at Gallery Mack, Seattle, WA.

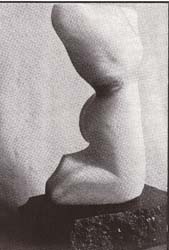

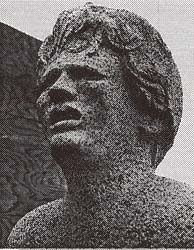

Stephen Sandry: We start by looking at one of Tracy's works, a standing figure with her face buried in hands. The figure is approximately 42" tall in marble, entitled "Sorrow".)

Tracy Powell: This image came to me the day that Yitzhak Rabin got killed. The television news showed a woman sobbing into her hands. That's the human condition! I walked into the shop and saw this block of marble which had been sitting here for a year, and the idea for the piece popped right out. On the carving bench, the figure read as full size. But when I put it down on the floor, I saw "this is a girl". The image was transformed, and her whole story was different. So, my thoughts were to combine that figure with a life-size mother-type figure, perhaps with her hand reaching out to the child. (Tracy has been considering this work for an open competition for an art purchase by Harborview Hospital, Seattle W A. The general theme for the commission is healing.)

SS: Certainly sorrow and grief fit well with the healing theme, being precursors to deep healing.

TP: Maybe just by herself, she could be useful as a healing instrument. I think that's a really important function of art: to touch that vulnerable part of somebody else without hurting them. Saying it's okay to do this (cry, feel sorrow); not to force anybody to cry, but just to say it's okay.

Technically its not very good at all. The proportions are bad, and I should have tried harder for the drapery. But, it works. Here's another piece, "Cloud Swimmer", in marble. This boulder was in a stream in Eastern Washington. In the creek it glowed, and sparkled.

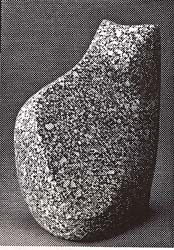

SS: Where did you find the idea for "Cloud Swimmer"?

TP: From the rock, but it took a while to figure out. At first I tried too hard. There's no distinguishing shape to the stone, and I was trying too hard to find some shape. Until I realized, it's just a cloud, with little pieces of the swimmer peeking out. That's all you have to do, fmd a face here, a knee there, and let the rest go.

SS: This area, the Skagit Valley, seems to be an inspiring place to be, a place for artists to get inspiration.

TP: There are powerful primal forces that come together here. The Skagit River and Puget Sound come together, and Mt. Erie is the remnant of an old volcano. It's the basalt plug--all that's left of the old volcano after it eroded away. You've got the mountains, the river, and the forest to remind you of the primal elements.

SS: I'd like to talk about your history, particularly about your path as an artist. Where are you on that path?

TP: I'm in kindergarten!

SS: What do you mean? You've been seriously carving in wood and stone for about fifteen years. You've done lots of work. The work shows competence and confidence. You are producing regularly. How are you still in kindergarten? You've obviously learned enough to make a statement.

TP: No, not really. I feel that I'm getting closer, though. I think I'm still working on craft. The" statements" come later. I'm learning the "voice" now. I'm still learning the technical aspects: how do you hold the tool, how hard do you ~rike with the hammer, those kinds of things. And the material--what can you do to it without hurting it. How do you get it to do what you want it to do.

And it's understanding the forms. I've been playing with this one now for the last couple years. It's a leaf, and it's a flame, and it's a wing. It comes up to a point, and I see this everywhere. I'm constantly playing with that, redrawing the same form, hoping to understand it and learn what it's talking about. Other forms are the figures. I'm learning more about that and enjoying that a lot more.

SS: Perhaps you stay vital if you are a leamer, a student of anything you are attempting.

TP: There are things I think an artist should say. There is some sort of purpose to our work. But to express these ideas can be difficult. In writing a great poem, you've got to know your language so well that the words just spill out of your mouth. Robert Bums, or Bob Dylan ... although we may not have seen it, there was probably a great learning process for them to go through.

The skills have to become second-nature. It has to do with elegance. This I learned from a math teacher who sought elegant solutions to complex math problems. When you tear away all the bullshit, there is an elegance in the universe which we are striving to glimpse. For him the way to do it was "farout" math. He was right. Whenever you glimpse something like that, it's a big AH HA! 1 think you learn and then you unlearn.

SS: How long have you been actively carving?

TP: Since we moved to the Skagit Valley in 1980. Prior to that 1 had been working for the city of Everett Parks Dept. and playing a bit with art. That time was mostly devoted to work and family. I was hanging on to a little (artistic) thread that I knew was in the background and that I would get back to later. Prior to family life, I was bumming around, living on the streets--being inspired by Jack Kerouak! I painted pictures on people' s walls, ceilings, sheets, blankets.

SS: What led you to carving?

TP: I had enjoyed whittling as a Boy Scout. Later I was introduced to Indian art. I found the Northwest Indian art to be very exciting: masks, totem poles, and cultural paraphernalia. I started playing with copying some of those forms, as a hobby. My job with the parks led me into management, giving orders to thirty people, which I hated. It drove me berserk. That's why we moved to the Skagit valley. My head was ready to separate from the rest of me. My artist spirit was pretty well smothered. It felt like moving here was the only place I could survive. It seemed like a life-or-death matter. I worked with my brothers here at boat building and odd jobs. Eventually, I started my woodcarving business, doing signs for boats and businesses. 1 worked at another parks job, but kept the carving going.

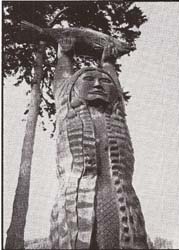

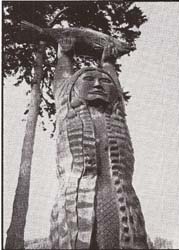

I carved a large cedar resnrrection figure ("The Burning Christ") for a church in Anacortes (4'xlO'). I worked for the Samish tribe and spent a year carving the "The Maiden of Deception Pass (24'h x 5' dia.) sited at Deception Pass. I then did cnltural preservation work for the tribe, cataloguing artifacts. I wrote a book on woodcarving in Co-Salish sty Ie (Handbook For Carvers: The Samish School of Co-Salish Woodcarving), this was about the local Native style (Vancouver Island to Oregon) which hadn't been written about. And I taught classes in this carving style. Working with the tribe, I saw how connected they were to the past cultural heritage. Things were still alive that had been going on for countless generations connected to this area. Going through that process as a voyeur made me want to find out where we came from, to get connected to that past. This has taken me to studying Welsh, Irish, Scottish history, and back into Celtic history. I'm looking for a Druid (the shaman class of Celtic and Iberian society) to talk to. There's written material dating to 500a.d. telling stories that were old then. These feel important to me, as if I can almost understand them. Some of the symbols I'm interested in come from this period.

SS: One of the things I'm interested in are the ideas and work that come through us unselfconsciousIy: ideas that flow from the universe beyond our limited selves. It appears like your work flows for you.

TP: I'm striving for that. As I said before, one thing I've been struggling with lately is abstract versus figurative work. All the abstract things that I do are basically two dimensional, they have two separate sides. In figure work it's three dimensional, every angle is a different picture of it. When working with a figure, it just comes naturally to work in 360 degrees and it's truly three dimensional. Bul. I haven't found that facility with abstract forms. I call them two and one half dimensional. more of a picture than a sculpture. I'm an admirer of Rodin. And one of his rules was that the sculpture had to be perfect all the way around, including from top and bottom views. That was a complete sculpture if it had that trueness. That's tough!

The other thing is a concept. Bill Holm and Bill Reid discussed in their book on Indian art, an idea called "emergent line". It is not a line that you draw, but a line that happens when you carry one plane in one direction, and you bring another plane up to it. Wherever they meet, that line emerges. Those kinds of lines have a certain grace to them. Those lines result from true three dimensional activity. You don't draw them in; they happen. That's a wonderful thing. They come out the cleanest and with grace. I think that's where I'm trying to go. Because you didn't force these lines to happen, yon allowed them, they've really got a presence. Maybe that's the "elegance", those things that happen "behind your back".

SS: What are your favorite stones to work with?

TP: The oolitic limestone. I enjoy all the stones, but limestone is by far the most fun.

SS: What qualities do you like about it?

TP: It doesn't get bright. It's very uniform in color. It makes nice shadow. In the stones with more color and pattern, they fight with the sculptural form. The other thing is that I do it all with hand tools. With a good point you can move this limestone fast. With the harder stone you have to hold the image in mind for so long. It takes much more time to get to where the figure is. It can turn around on you before you get there!

SS.: What is your source of inspiration?

TP: Life, The Force. Trying to interpret or describe that. One way to say it is that it's all religious art--it's Life. I want to describe it and tell how beautiful it is. There's a great joy in doing it. It's sensual as well as intellectual. That's why the hand carving in soft stone is so much fun. You can get intimate with the material and the image.

SS: With the flame/leaf/wing image, do you know why it is important to you?

TP: No, I don't. It just seems to be important. There are many natural objects that have that form to them. There are man-made symbols, like the yin-yang and the infinity symbol. It's primal. If I make enough variations on that, I might stumble upon an answer. There's a secret in there.

SS: Is it important to you to have your work shown, seen by others?

TP: It wouldn't have much function, if it was just for me. It's a lot of fun to do, but I don't particularly get off on looking at them when they're done. If someone else responds to it, then its complete.

SS: Perhaps that's the whole "conversation".

TP: If it doesn't go beyond you, what's the point? That's where fme art is different than spoken or written language. It's not very precise. It's more solid and tangible than other communication, but more up to individual interpretation. You're not saying one thing. You're saying a lot of things. The object becomes something else in the eyes of each person that looks at it. This can also change over time as perspectives change.

SS: Do you have a story in mind while working on a piece, particularly the figurative work'?

TP: Yes. When I'm carving a figure, I imagine a whole scene that it's in. The other figures, the scenery. the sounds and the smells. It's got a whole little world. But, the stone figure is all I can pluck out of that scene. That's why I may get back to painting again, to show the whole scene. That's part of the conversation with the piece. Over the time it takes to create a piece, that inner story or background may change several times. This may cause me to change the idea I started with originally.

SS: What is your work pattern?

TP: I squeeze studio time in amongst the other things I have to do. I'm always working on half a dozen images, but I try to do only one piece at a lime, all the way through.

SS: Where are you going with your art?

TP: I want to get better. I want my pieces to say what they need to say. Elegance, that's what I'm after: something like clearing the pool table with one shot. Start with a rock; hit it once and have a perfect sculpture emerge. That would be an elegant act!

SS: How are you involved with N.W.S.S.A.?

TP: I've been a member since '92 and was recently elected to a position on the Board of Directors. I've received so much from this group: technical skill and inspiration, guidance, support and love. I want to give a little bit back, to keep the wheel spinning.

SS: What is your vision for the group?

TP: I think it would be nice to have a permanent home, a place that was equipped for what we want it to do. It would be good to have a big studio somewhere that we could all use. The idea of a sculpture center at Sandpoint in Seattle (formerly the Naval Air Station) is a wonderful dream. I love that! It is supposed to be a dedicated art environment. Our group is on the list to be part of it, although it will take a long time before it is sorted out.

SS: Well Tracy, have you got any parting comments?

TP: Most human activity is either pointless or worse, except art. I think it's the only thing worth doing.

SS: Many thanks, Tracy, for all your contributions.