Joseph Kincannon and the Portal of Stone

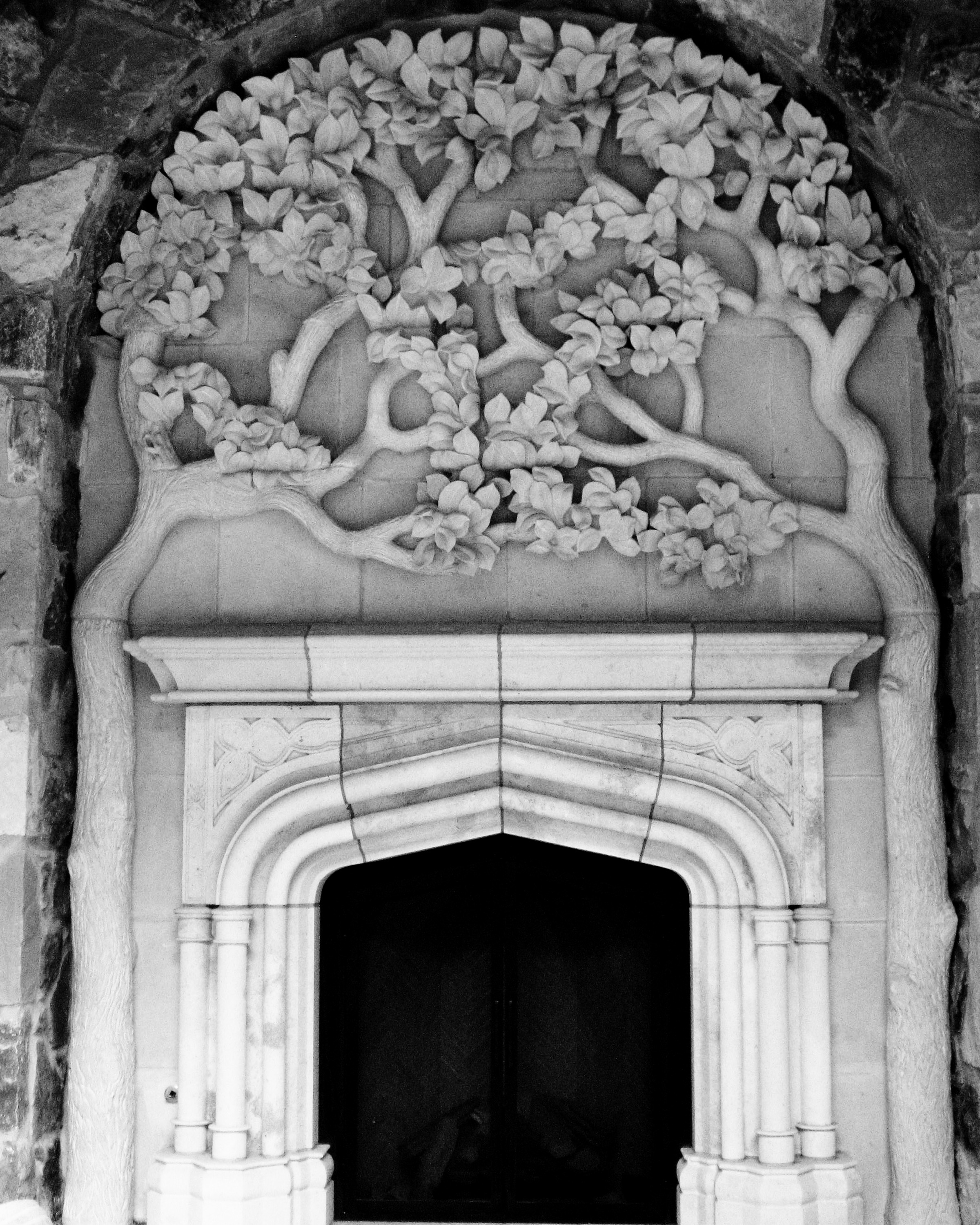

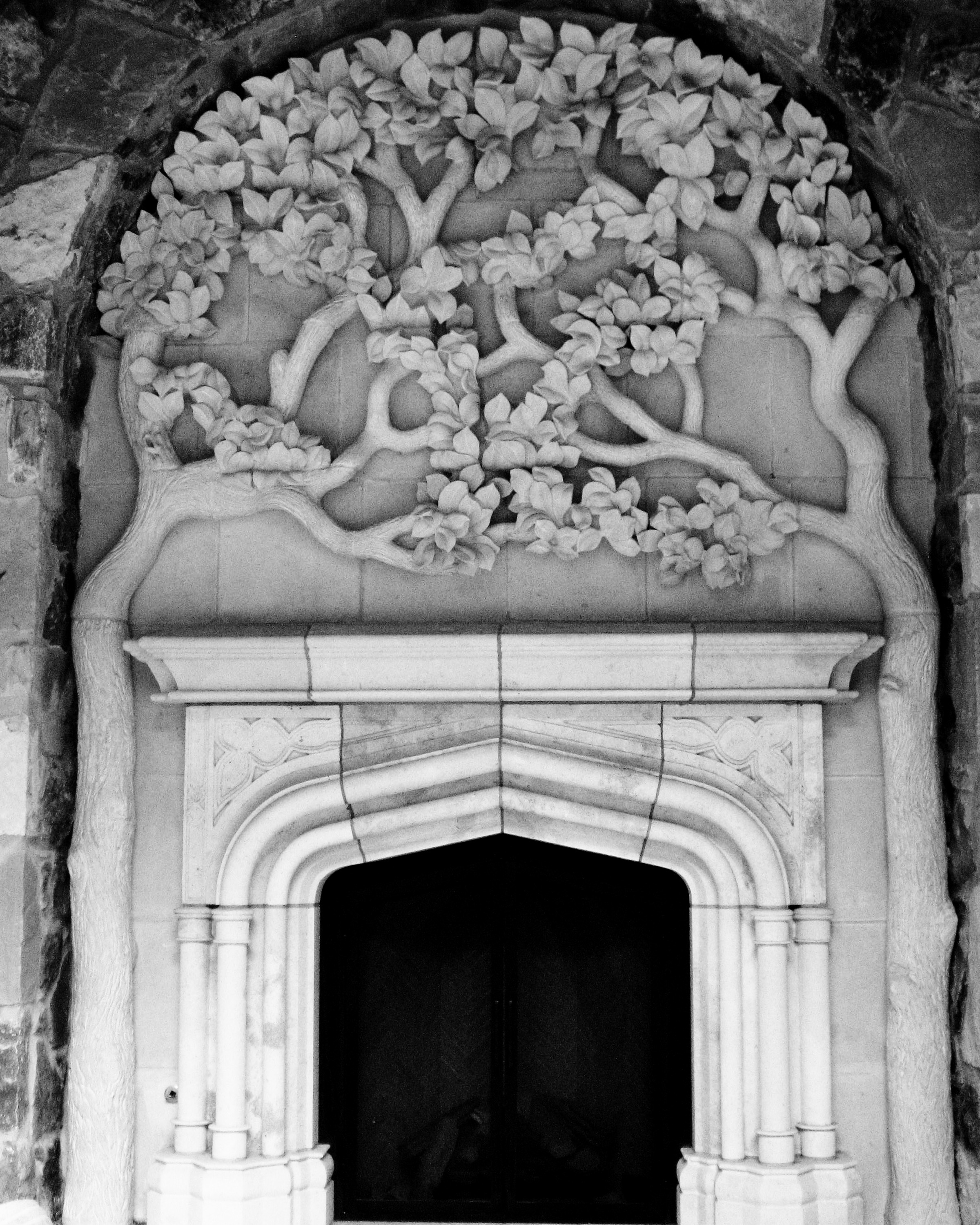

In 1979 I entered the world of stone through an unusual portal; a portal at a cathedral, to be specific, The Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City.  As cathedrals go, this mammoth edifice is a 19th century show of American might. It’s a cathedral to beat all cathedrals… in size, anyway. The interior floor is two football fields in length. The ceiling height is 120 ft. at its highest and with massive granite walls sheathed in a thick skin of limestone. The place is dirty, dank and cold just like the city it sits in, and I loved it instantly. I had never seen such grand architecture. There was nothing timid in the construction of this building. I was immediately struck by how the roaring city outside is silenced upon entry.

As cathedrals go, this mammoth edifice is a 19th century show of American might. It’s a cathedral to beat all cathedrals… in size, anyway. The interior floor is two football fields in length. The ceiling height is 120 ft. at its highest and with massive granite walls sheathed in a thick skin of limestone. The place is dirty, dank and cold just like the city it sits in, and I loved it instantly. I had never seen such grand architecture. There was nothing timid in the construction of this building. I was immediately struck by how the roaring city outside is silenced upon entry.

By the way, when I arrived at this cathedral it was not to be a stone carver, but to work in their gift shop. My brother had landed me a summer job. He wanted to broaden my horizons. And broadened they were. People streamed in from every corner of the world. Tour buses would unload a stampede of weary travelers every hour on the hour. They’d meander through the cathedral in a muted daze, but when they entered the gift shop that was with real purpose. It may have only been a gift shop, but to me it was like the United Nations.

Outside of this quiet stone fortress, New York City rumbled away. A place full or danger and adventure. Too intimidated by the subway, I used to walk everywhere. Along with the frenetic buzz of activity, ever present, was a backdrop of extraordinary building facades adorned with ornament. The past of this great city was just staring down on a new crop of inhabitants. It was easy for me to imagine immigrants fresh off of Ellis Island walking around inspired by this mystifying landscape. I couldn’t fathom how these things were made. I knew nothing about nor had ever given any thought to stone.

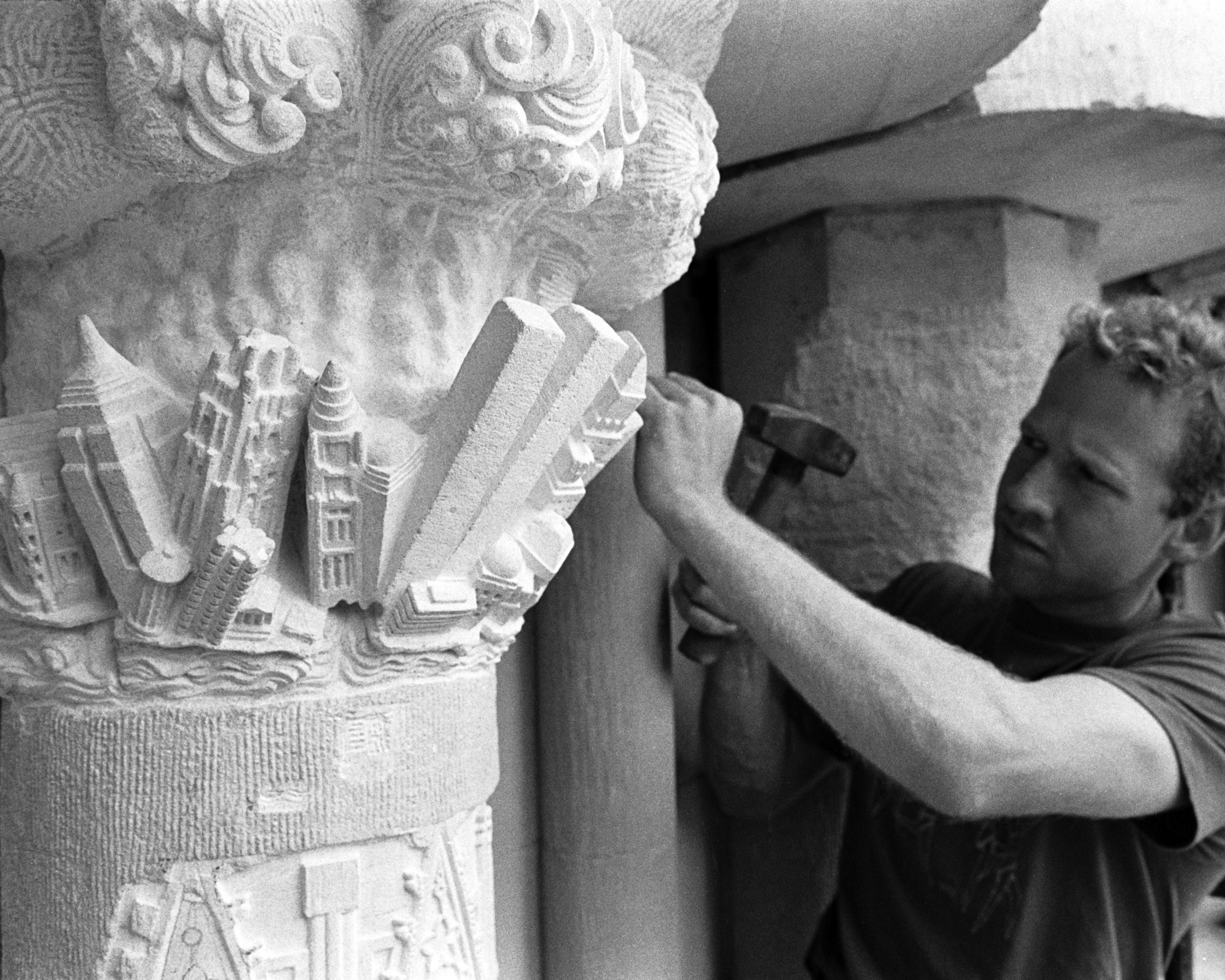

Outside of this quiet stone fortress, New York City rumbled away. A place full or danger and adventure. Too intimidated by the subway, I used to walk everywhere. Along with the frenetic buzz of activity, ever present, was a backdrop of extraordinary building facades adorned with ornament. The past of this great city was just staring down on a new crop of inhabitants. It was easy for me to imagine immigrants fresh off of Ellis Island walking around inspired by this mystifying landscape. I couldn’t fathom how these things were made. I knew nothing about nor had ever given any thought to stone. My first glimpse at the work behind the scenes happened unexpectedly one day as I walked to lunch. There were people pounding all hell out of a giant slab of limestone with crude hammers and chisels. Eight or nine young men and women and an older red-faced man in a tweed cap were hard at work. The old man was English and the others were all African-American and Puerto Rican. This was the beginning of a Harlem hood apprenticeship program.

The idea was to train young people from the neighborhood in the methods of cutting and carving limestone. The purpose being to continue the construction of the Cathedral as it was halted at the start of World War II. The main effort was to build a tower on the west front of the Cathedral.

I was eighteen years old and it was then that I knew what I wanted to do with my life. Also I had an edge, as my brother, Jeep, within a year had become one of the top stone cutters in what was to be known as “The Yard.” With his support, and my nagging perhaps for another year, I gained an opening that led me into the world of stone.

My first job was to run a quarry saw. This was a formidable machine equipped with a sixty inch circular blade designed to cut through large blocks. It was the second step of the quarry blocks’ journey through our workshop. The first stop was the frame saw, which was essentially a mechanical two-man saw. From my station, the stones were moved into the “cutting shed” which is where the stone cutters would fashion the stones into any number of designs. They relied on templates transferred from the original architectural drawings dating back to the 1890’s. All this drafting and transferring was done by hand. There was no question regarding our role. Quarry blocks entered one end of the building and intricately carved stones exited out the other. The stones were then stored outside until the spring at which point we would shift to the roof to build the actual tower.

My first job was to run a quarry saw. This was a formidable machine equipped with a sixty inch circular blade designed to cut through large blocks. It was the second step of the quarry blocks’ journey through our workshop. The first stop was the frame saw, which was essentially a mechanical two-man saw. From my station, the stones were moved into the “cutting shed” which is where the stone cutters would fashion the stones into any number of designs. They relied on templates transferred from the original architectural drawings dating back to the 1890’s. All this drafting and transferring was done by hand. There was no question regarding our role. Quarry blocks entered one end of the building and intricately carved stones exited out the other. The stones were then stored outside until the spring at which point we would shift to the roof to build the actual tower.The training was intense and the pay, poor. Four years of cutting stone moldings, arch stones and basic building blocks. Three years of carving ornament: foliated capitals, grotesques, arch spandrels, etc. and all by hammer and chisel. For a period, we did everything, but eventually the work was subdivided stone cutters, and stone carvers with a team of masons building the tower. I became a carver.

The first idea drilled into us was the need to be anonymous. We weren’t permitted to sign our work or bring attention to whom did what. We were strictly “architectural sculptors” and none of us had a problem with this commitment. We were accompanists. The building was the great work.

As a representational carver, I loved carving anything from nature. Foliage held my greatest interest, and still it does. I found that the fluidity and organic approach allowed for a great amount of freedom. Unlike statuary or grotesques, these works require extensive drawing and model making. I loved it all, but carving foliage allowed me to take off and develop as a carver.

There was a lot of repetition. For example, we had to produce dozens of crockets which are bulbous foliated cabbage forms that march up the corners of pinnacles. We had a model to follow, but naturally each carving was slightly different. When a pinnacle was constructed, each crocket had its own pulse. The carvings appeared to be moving. This in effect draws the eye upward and follows the line of the stone. In an age of automation, it’s important to note that this movement or pulse exists because the human hand produces these carvings with all necessary mutations. The stones appeared to be alive.

The structured environment of the Cathedral stone yard and building program appealed to me, but at a certain point, I felt the need to cut the moorings and explore a little. At nighttime, “The Yard” was available which offered a great opportunity to work more freely. During this time I stumbled into the direct carving approach. This was not taught or encouraged at the Cathedral, and it turned me on my head. I was on fire and convinced myself that I had unlocked the key to all the great carvings throughout history. I would pour through books looking for great works of sculpture that might have employed this very approach.

The structured environment of the Cathedral stone yard and building program appealed to me, but at a certain point, I felt the need to cut the moorings and explore a little. At nighttime, “The Yard” was available which offered a great opportunity to work more freely. During this time I stumbled into the direct carving approach. This was not taught or encouraged at the Cathedral, and it turned me on my head. I was on fire and convinced myself that I had unlocked the key to all the great carvings throughout history. I would pour through books looking for great works of sculpture that might have employed this very approach.

Like jazz from the fifties and sixties, I felt that carving was all about pure improvisation. No more being shackled by drawings and models or any preconceived notions. I wanted to” “find my way” through the stone with only the stone itself informing me. I wanted to be the John Coltrane stone carver. At this point, I begin tearing into the stone. I worked at a fevered pace and learned a great deal. Eventually, I circled back with an understanding of the importance of prepared drawings and models, but that tornado-like yearning and years of exploration still drives me today. I worked at that cathedral for twelve years and it was truly a great experience. My move to Texas in 1992 and the modern environment that I have since worked in has not been an easy transition.

The cathedral was my only school, and I thought modern architecture was an abomination. I looked around at these cold glass buildings and saw nothing to entertain the eye. Austin Texas to my thinking had no continuity from one block to the next. I just couldn’t wrap my mind around how architecture, or how we, had gone so far astray. Why would people accept this inferior typology?

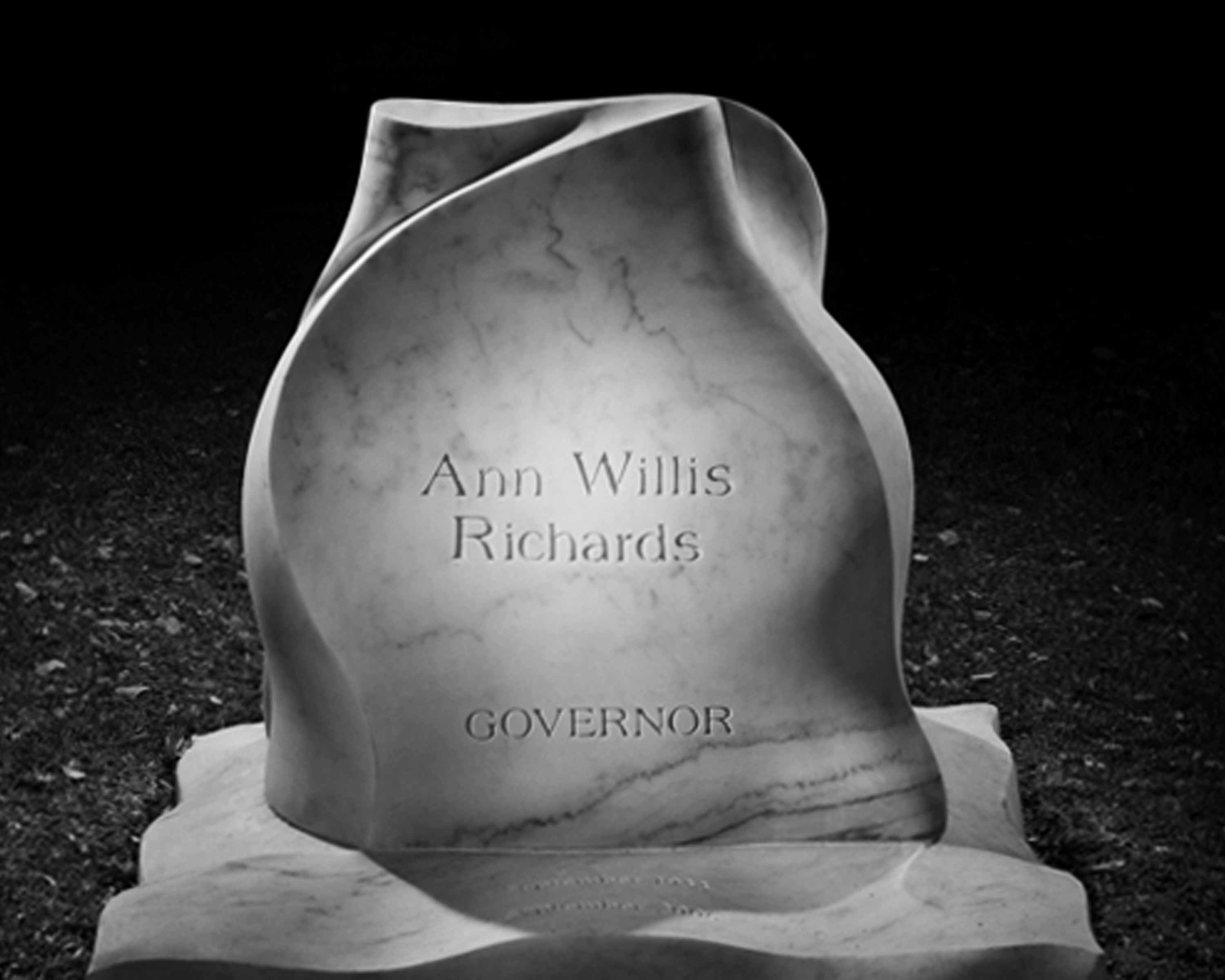

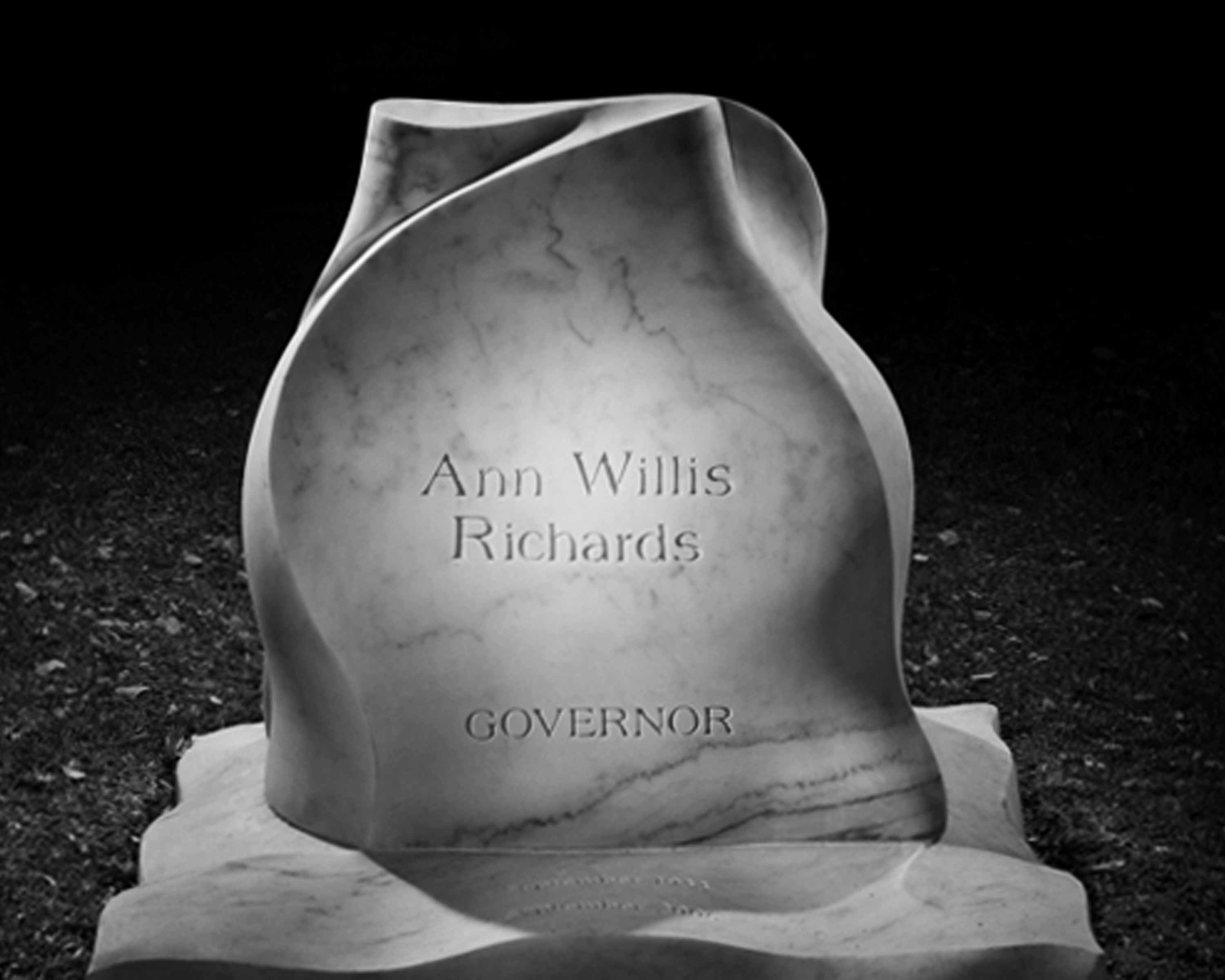

I felt so removed from the world of European architecture, even from New England. My training and aesthetic seemed to be antiquated. So, my wife and partner, Holly, who’s trained as an architect, and I named our new studio, ARCHAIC. And with the help of our two brothers, Jeep and Richard, and a growing number of apprentices, we began carving statues, fountains, fireplaces and restoring Texas’ courthouses and churches. Eventually because we both have a passion for art we moved into the realm of public sculpture and urban design.

As an artist, I slowly backed off of the flamboyant and highly articulated designs fitting of for a cathedral. I began to explore geometric forms that are more in tune with the palette of our new landscape. I began looking at the work of architect Carlo Scarpa and the sculpture of Isamu Noguchi. I took more interest in the subtle interplay of planes, angles and the explorations of textural treatments. My stone carving approach began taking fewer steps to achieve purpose with a block of stone. Mind you, I am still on this journey. I’m also very excited about our studio’s next phase. We are on the move again and taking our chisels to the hauntingly, beautiful world of the Old South. And while I will not be carving under the arches of a Cathedral, I will be under the moss-laden oaks trees of Savannah, Georgia. And although we changed our studio name from ARCHAIC to KINCANNON STUDIOS in 2008, perhaps it’s time to rethink this story.

The structured environment of the Cathedral stone yard and building program appealed to me, but at a certain point, I felt the need to cut the moorings and explore a little. At nighttime, “The Yard” was available which offered a great opportunity to work more freely. During this time I stumbled into the direct carving approach. This was not taught or encouraged at the Cathedral, and it turned me on my head. I was on fire and convinced myself that I had unlocked the key to all the great carvings throughout history. I would pour through books looking for great works of sculpture that might have employed this very approach.

The structured environment of the Cathedral stone yard and building program appealed to me, but at a certain point, I felt the need to cut the moorings and explore a little. At nighttime, “The Yard” was available which offered a great opportunity to work more freely. During this time I stumbled into the direct carving approach. This was not taught or encouraged at the Cathedral, and it turned me on my head. I was on fire and convinced myself that I had unlocked the key to all the great carvings throughout history. I would pour through books looking for great works of sculpture that might have employed this very approach.Like jazz from the fifties and sixties, I felt that carving was all about pure improvisation. No more being shackled by drawings and models or any preconceived notions. I wanted to” “find my way” through the stone with only the stone itself informing me. I wanted to be the John Coltrane stone carver. At this point, I begin tearing into the stone. I worked at a fevered pace and learned a great deal. Eventually, I circled back with an understanding of the importance of prepared drawings and models, but that tornado-like yearning and years of exploration still drives me today. I worked at that cathedral for twelve years and it was truly a great experience. My move to Texas in 1992 and the modern environment that I have since worked in has not been an easy transition.

The cathedral was my only school, and I thought modern architecture was an abomination. I looked around at these cold glass buildings and saw nothing to entertain the eye. Austin Texas to my thinking had no continuity from one block to the next. I just couldn’t wrap my mind around how architecture, or how we, had gone so far astray. Why would people accept this inferior typology?

I felt so removed from the world of European architecture, even from New England. My training and aesthetic seemed to be antiquated. So, my wife and partner, Holly, who’s trained as an architect, and I named our new studio, ARCHAIC. And with the help of our two brothers, Jeep and Richard, and a growing number of apprentices, we began carving statues, fountains, fireplaces and restoring Texas’ courthouses and churches. Eventually because we both have a passion for art we moved into the realm of public sculpture and urban design.

As an artist, I slowly backed off of the flamboyant and highly articulated designs fitting of for a cathedral. I began to explore geometric forms that are more in tune with the palette of our new landscape. I began looking at the work of architect Carlo Scarpa and the sculpture of Isamu Noguchi. I took more interest in the subtle interplay of planes, angles and the explorations of textural treatments. My stone carving approach began taking fewer steps to achieve purpose with a block of stone. Mind you, I am still on this journey. I’m also very excited about our studio’s next phase. We are on the move again and taking our chisels to the hauntingly, beautiful world of the Old South. And while I will not be carving under the arches of a Cathedral, I will be under the moss-laden oaks trees of Savannah, Georgia. And although we changed our studio name from ARCHAIC to KINCANNON STUDIOS in 2008, perhaps it’s time to rethink this story.