My first serious encounter with stone was a mixed-materials piece in 1982, featuring a 300-pound granite glacial erratic that I had dragged from the woods. Working on this piece got me totally hooked on stone and particularly on granite. Since my training was in metal casting and fabrication and I knew nothing about carving stone, I naturally decided to become a stone sculptor.

My first serious encounter with stone was a mixed-materials piece in 1982, featuring a 300-pound granite glacial erratic that I had dragged from the woods. Working on this piece got me totally hooked on stone and particularly on granite. Since my training was in metal casting and fabrication and I knew nothing about carving stone, I naturally decided to become a stone sculptor. My art in the three-and-a-half decades since divides into three phases: eighteen years of abstract granite and basalt sculptures in human scale, a decade of chasing the metaphor of a tree growing from rock, and my recent series using visual metaphors autobiographically. My process has always started from a vision that pops into my mind suddenly, although often after I’ve been thinking about a subject for some time. I work the design further in my head and on the stone, rarely using drawings or maquettes. When I did the Rock Becoming Tree series, the essence of my sculpture became conveying the metaphor using a limited number of symbols. In the Love & Loss series that I just finished, the most important feature was communicating emotion.

The recent change in my work came from my wife Judy’s illness and death from Alzheimer’s Disease. Family caregivers for someone with dementia die at a rate sixty-three percent higher than the general population, because the experience is so exhausting and traumatic. After her death, I felt totally crushed and floundering in a world with no meaning. Caregivers are encouraged to write about their experience in order to process their grief. I decided, instead, I would use my years of training to make sculptures about it.

Even though I didn’t have time to sculpt while caring for Judy, visual images kept arising as a way of understanding what was happening. I began the Love & Loss series in the fall of 2013 to turn some of these ideas into physical reality. Fortunately, I was forced to make new work since I would be one of the featured artists in a Green Art show at Karla Matzke’s gallery in 2014. Because of the show’s theme I used trees for the subject of the first sculptures in the series.

Even though I didn’t have time to sculpt while caring for Judy, visual images kept arising as a way of understanding what was happening. I began the Love & Loss series in the fall of 2013 to turn some of these ideas into physical reality. Fortunately, I was forced to make new work since I would be one of the featured artists in a Green Art show at Karla Matzke’s gallery in 2014. Because of the show’s theme I used trees for the subject of the first sculptures in the series. The first, Lost World, is a tree with two trunks emerging from the stone and winding around each other, leading to highly polished foliage flowing back into the rough, pale rock. Its companion piece, New World, is a photographic negative of the first work: a pale, shattered, single trunk that rises out of the dark rock and ends in pale, sparse foliage scattered across the top. The first symbolized the richness of my life with Judy while the second was my bereavement in a new world that lacked strength and substance.

I exaggerated the roots and trunk of The Tree of Life is Watered with Tears to emphasize solidity and contorted its shape to represent growth and struggle. The tree waters itself with its own tears. I carved them out of the same stone to show how integral pain is to life’s experiences.

In Will The Circle, two trees arise from intertwined roots to form a circle interrupted by a gap that is slightly off center, as well as cracks lower on the trunks. The idea comes from the Carter Family song, “Will the Circle be Unbroken,” which is about family members reuniting in heaven after death. Since neither Judy nor I believed in an afterlife, I chose the title and the form to state, no, the circle will never be intact again.

In Will The Circle, two trees arise from intertwined roots to form a circle interrupted by a gap that is slightly off center, as well as cracks lower on the trunks. The idea comes from the Carter Family song, “Will the Circle be Unbroken,” which is about family members reuniting in heaven after death. Since neither Judy nor I believed in an afterlife, I chose the title and the form to state, no, the circle will never be intact again. After the Green Art show, I shifted the series away from using trees and used a variety of forms. In these, associative thinking played a major role: a nub of an idea would start a cascade of related ideas that I then would try to integrate into a coherent whole.

Caregiver Finds Respite came together from several thoughts. The flat face of the wedge-shaped basalt gave me the idea of using stone as a support for a narrative rather than carving it. I connected it with the myth of Sisyphus and how, as a caregiver, I woke up each morning feeling I had to roll the stone up the mountain, only to start over the next day. The eight ball in place of the stone popped into my mind from the phrase “behind the eight ball,” meaning you were stuck. It morphed into the Magic 8 Ball of my youth with its ambiguous answers reflecting the constant uncertainty of caregiving. I made three different figures over the course of completing the piece, each progressively smaller as I reflected on the enormity of the daily task. The figure is taking a break from his labors, but briefly, and in a very precarious place.

Phoenix expresses my feelings that caregiving was a journey through fire that ended in ashes. I’d bought two wooden birdhouses hoping that Judy would get interested in painting them, since people with dementia can enjoy crafts projects. Unfortunately, her dementia was too advanced, so they sat untouched until after her death. I decided they could represent my life before and after Judy’s illness, and that the bole of a tree I’d removed at my new home could stand in for the journey. I painted one birdhouse as The House of Love with polymer clay figures of Judy, me and the dog on the porch and the second as The House of Ash with me hanging by my fingernails while the dog watches. I carved and burned the trunk to symbolize the ordeal of the journey. The text engraved in the trunk is drawn from the behavior log I kept in order to try to improve my interventions in Judy’s behavior. The sentences alternate between things she said that were hurtful to ones that were loving. I found this part very difficult: I was unable to open the journal for several months to look for text, until I realized that the painful ones were already seared in my memory. Finding loving remarks everywhere when I finally looked greatly changed my feelings about what had happened.

Phoenix expresses my feelings that caregiving was a journey through fire that ended in ashes. I’d bought two wooden birdhouses hoping that Judy would get interested in painting them, since people with dementia can enjoy crafts projects. Unfortunately, her dementia was too advanced, so they sat untouched until after her death. I decided they could represent my life before and after Judy’s illness, and that the bole of a tree I’d removed at my new home could stand in for the journey. I painted one birdhouse as The House of Love with polymer clay figures of Judy, me and the dog on the porch and the second as The House of Ash with me hanging by my fingernails while the dog watches. I carved and burned the trunk to symbolize the ordeal of the journey. The text engraved in the trunk is drawn from the behavior log I kept in order to try to improve my interventions in Judy’s behavior. The sentences alternate between things she said that were hurtful to ones that were loving. I found this part very difficult: I was unable to open the journal for several months to look for text, until I realized that the painful ones were already seared in my memory. Finding loving remarks everywhere when I finally looked greatly changed my feelings about what had happened. Phoenix gave me a chance to incorporate text, an idea that had interested me for some time. I thought using a folk art style might lure the viewer into thinking the work was supposed to be charming, giving the text and symbols a greater emotional impact when they looked more closely.

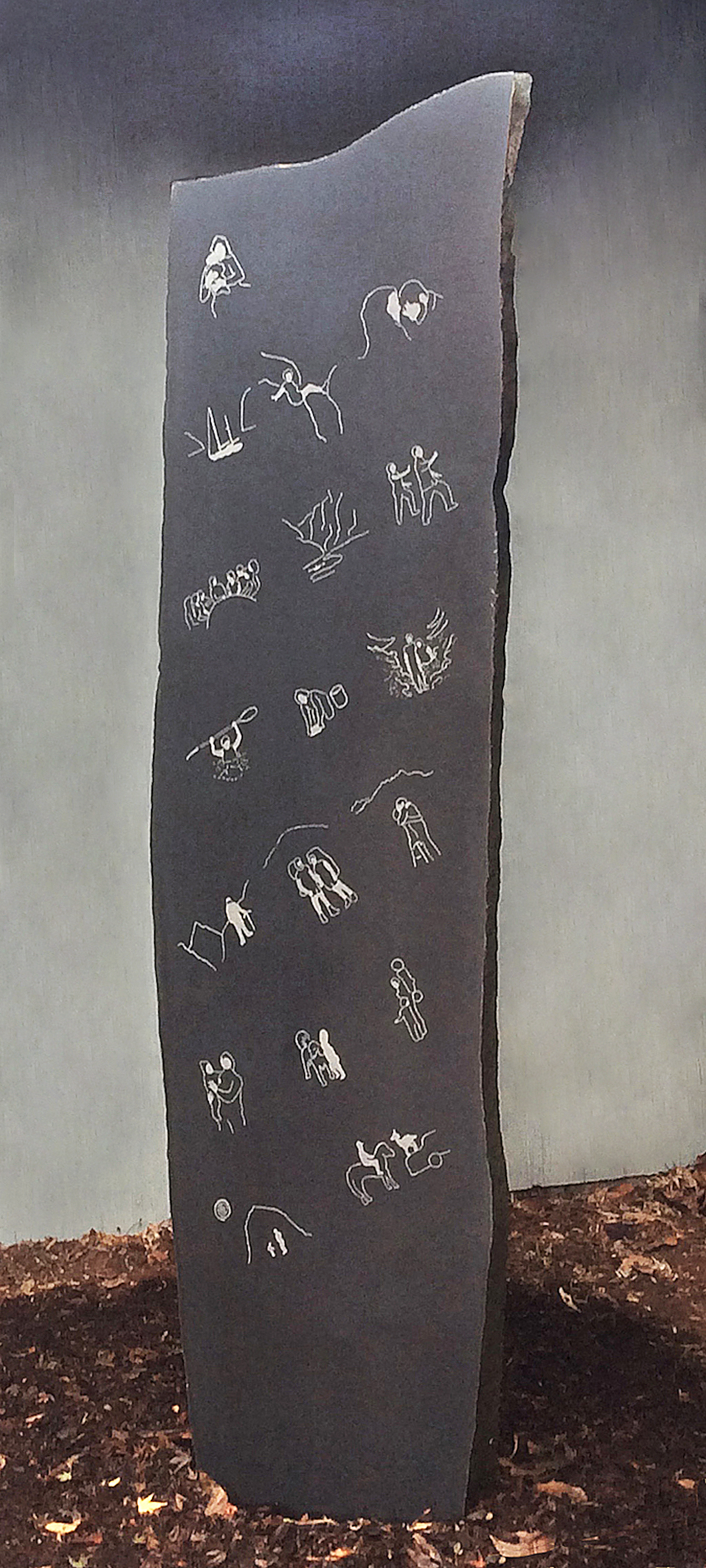

In Judy’s Memory Stone, I used petroglyphs as the graphic element, placing them in a sequence that narrated her life, similar to what one might find on a stele. In 2010 when Judy’s memories were clearly slipping away, I thought that depicting her stories might help her reminisce. I chose petroglyphs, because she had really enjoyed exploring rock art in the Southwest. Although I worked out most of the graphic design that winter, I was unable to do the piece until 2017. This sculpture is the one that is the most about the love in the Love & Loss series.

IF (you really love me) was my goal for the series, representing releasing Judy into the void. It is based on a dream I had the week after Judy died, in which she had returned to life but was still demented, so I was caring for her again. She then disappeared, and it was my fault since I obviously hadn’t been watching her closely enough. She reappeared, and I gave her a big hug, saying, “I love you so very much.” She replied, “If you really love me, you’ll let me go.” The sculpture centers on the void carved into the heart of the granite block. The walls are highly polished to contrast with the pitched, sawn, and ground exterior. The figures are carved from the same block, and the figure being released is polished to connect with the void, while the remaining figure is the same rough grey finish as the outside surface.

I finished the series this July with The New Normal, which I see as actually the first one. The title was a phrase the neuropsychologist used when he gave us Judy’s diagnosis ten years ago: that dementia would be the new normal. I carved the piece out of a battered piece of cherry wood so that I could burn out the part of her head where Alzheimer’s destroyed her mind and led to the “new normal” of confusion and fear. This was another slow one to finish, since I hadn’t done a representational figure in almost forty years, had only done one wood sculpture previously, and mostly because I worked surrounded by a pile of different photos of Judy which kept overwhelming me emotionally.

I finished the series this July with The New Normal, which I see as actually the first one. The title was a phrase the neuropsychologist used when he gave us Judy’s diagnosis ten years ago: that dementia would be the new normal. I carved the piece out of a battered piece of cherry wood so that I could burn out the part of her head where Alzheimer’s destroyed her mind and led to the “new normal” of confusion and fear. This was another slow one to finish, since I hadn’t done a representational figure in almost forty years, had only done one wood sculpture previously, and mostly because I worked surrounded by a pile of different photos of Judy which kept overwhelming me emotionally. Completing the series really did yield the hoped for result: I made the transition into another world that is no longer about grief and memory. I imagine that the passage of time has much to do with this outcome, since it’s been six years, but I also think that my self-imposed art therapy played an important role. At a minimum, I’ve been able to transform the lead of grief into the gold of expressive sculpture.

This summer I did a sculpture, Time, based on a vision that woke me in the middle of the night. It seems to be a contemplative look at time and change and has nothing to do with grief. It was a real delight to make. I’m now inundated with a range of ideas and a desire to work with a variety of materials. I’m looking forward to this new era in my sculptural life.