As I arrive at his home George is showing his sculpture to some customers at his dining room table. It is a nicely appointed room; the pieces are displayed in an attractive showcase and on various surfaces around the room. They are lighted with spotlights. Most are smaller pieces carved from marble and jade. His customers select two of the bird forms in Rainforest Marble. The birds are balanced so that they pivot on their plate-glass bases. George wraps them up and writes a personal note to accompany them. On the way out the door one of the people puts a 'hold' on one of the sculptures on the shelf.

GP: You see, those people who buy that little coffee-table sculpture for a wedding gift- they also work somewhere-perhaps at a firm downtown that would have influence on doing public artwork. The guy who owns one of your smaller works may be the one who will recommend you to be purchased into the corporate art collection.

We then head off to George's studio a few blocks away near Vancouver's Chinatown. It is a one-story industrial building with a paved surrounding yard right next to the train tracks. Trains occasionally thunder by...

GP: It's difficult for sculptors to find suitable downtown space to do their dirty work. A screaming diamond grinder will bring an irate neighbor faster than anything I know. I have a wonderful shop immediately adjacent to the railway tracks. If you think I make a little noise or dust, you should see what the railroad does! So they can hardly blow the whistle on me.

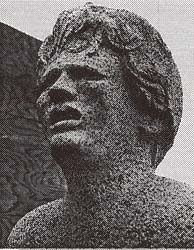

We proceed to tour his studio. We look at his 'Shadow Garden', a collection of large river boulders gathered together in a grouping. Each boulder is carved with different patterns of line and texture, hewn deeply to emphasize the shadow effect of sunlight shifts and with depressions designed to catch rain. We move mto the studio and view a work in progress-a large horse's head in startling blue sodalite which will be featured in his November show.

GP: It needs to be a little more 'equine', more graceful of line. Up to now it has the character of a carousel pony. Simplicity is the name of my game. Strength and power through simplicity.

The discussion shifts to showing sculpture.

GP: You'll find few people attempting to make a living carving stone who've had a successful relationship with a gallery. Few gallery owners know how to present sculpture. Most have a tendency to put the sculpture in the corner as an adjunct to their paintings. Few will actually feature sculpture nor light it properly.

Michael Binkley and I had our own gallery for two years. We made it a policy to show only sculpture abetted by lots of flowers in stone vases. There was not a painting in the place, because much as we like paintings, they steal the focus from sculpture and we wanted to make sales. And sell we did - a tremendous amount of sculpture from that delightful little showroom, both of us building our collector base tremendously. It was well lit with spotlights-a must if you want to sell sculpture. As you can tell, I'm opinionated about these things. But that is what has helped me survive. I've seen people set up home sculpture shows but they don't go to the trouble of installing proper lights, i.e., focused spotlights on every sculpture. It's half the battle. (Another of George's interesting opinions is that assigning a title to a sculpture can interfere with a sale if the client can't relate to the title. He tags his works with only generic descriptions.)

SS: When you price a piece of sculpture, what are the considerations? Why do you price the sodalite horse's head at $10,000?

GP: Clearly I didn't work it out 'by the hour'. The price in this case reflects an arbitrary value I have placed on its uniqueness and elegance, a factor that goes beyond the hard cost of producing it. It's priced for mystique, not practicality. However,l must know in my heart that the piece will be perceived to be worth the money. It may not sell. But who wants to be seen at a show where everything is cheap? What art writers would care to write about it? There are many people among us to whom $10,000 for a fine artwork is not significant. Such people do not want to buy what everybody can buy. They seek out that which is rare as well as beautiful. At our last Faces & Figures show, I sold a $15,000 piece and in the one previous, Michael sold a $19,000 piece and I sold a $6,000 piece both to one customer. Those people will be back to our next show with their friends-and they will be expecting an encore of something equally worthy. But as well, one's show must have many works priced between $250 and $750. There is an army of ordinary working people out there who love sculpture and they can and will put that amount on their credit card.

We examine the horse's head.

GP: I made this for our biannual Faces & Figures show about five years ago. It started out as a massive block of soda lite from a quarry near my home town in northern Ontario. It is a splendid stone, profound blue, nicer than the Lapis Lazulis you've seen. I showed it as a finished work, but although it was competent and adequate, it never really pleased me. It was not exciting. It was a playground pony rather than a spirited mare. So I put it away out of sight for four years and have now started recutting it. And I can already see that in this year's show it will convey the excitement it lacked before. Horses are not my forte, I should point out. I've had to struggle with this one. But it was almost a horse when I found it in the quarry.

SS: So what was your thinking in reworking it?

GP: I thought, if I do recut it, will it be a better sculpture? Or will it just be a waste of time? I firstly had to figure out what was wrong with it. After a four-year cooling off period it was easy to look at it clinically rather than passionately and see that the main problem was too much weight in the throat and an indistinct jaw-line. As well, the ears needed to be more drawn out and graceful. Clearly there was a more elegant horse lurking in there, it just needed some tweaking. So I got started recutting. I want a lot of money for it, so let's make it worth the money. I'll be also working on slightly 'doming' the flat bottom so that the horse will rotate when gently pushed. I discovered that in sanding the flat bottoms of my 'coffeetable' sculptures they have a tendency to round off. If the center of the resultant 'dome' be near the balance point of the carving, then it will rotate on its base, lending an agreeable kinetic value that a stationary piece does not have. It has become a trademark.

I love art. 1 love sculpture. But I've never considered myself to be a great artist. I go to the symposia and I'm envious of the abilities some of those sculptors possess, novices and experienced artists alike. I could take a lesson from most of them. My natural skill is in making sales. I genuinely like people and can relate well to almost anybody. I can sell things to people who didn't intend to buy in the first place. In the beginning, I didn't give much conscious thought as to whether I could be a success as a stone-carver. I just knew that even if I wasn't very good at it I'd still make lots of sales. I encourage all aspiring sculptors to work hardest on the sales part of their career. I hear some who say loftily that the purity of their work is all that counts and they will never compromise their principles merely to make sales. And that is very noble. But it usually ensures a career as a waitress or taxi-driver.

We tour George's studio. We visit the 'wet' room in which he does his waterfed carving and polishing. He has a drill press for core-drilling with water, a station with 10" x 1/4" carving blade running at 3400 RPM, and a station for sanding with both silicone carbide and diamond belts. (The carbide belts are not as aggressive but they are more flexible, he explains.) All machines are driven by permanently wired 220V electric motors. The room has a floor-drain to carry away the carving slurry into a cleanable catch basin. As well, he has a 20" diamond chopsaw which results in an 8" cutting depth, used for getting his raw material down to a carvable size with little waste. He considers this to be an essential for the serious carver. His compressor and air-powered carving gear as well as hand tools are in the main room, He

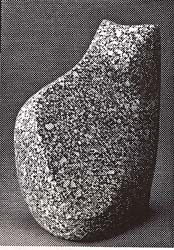

likes to work on pieces in progress in the outdoor yard where he also store his raw material. About the shop are example of 'utilitarian art' as he calls it: Granite benches and garden lanterns; stone oil-lamps and flowervases; and an attractive business-card caddy made with granite cores set in a concave base. He produced two hundred of these last year for presentation gifts for a bank. More hard work than

great art, he comments, but it paid the rent. "If you reserve the ability to make utilitarian items you can stay alive as a sculptor."

SS: What balance do you try to achieve between utilitarian items and fine art pieces?

GP: In a perfect world I would like to produce nothing but pure art sculptures the size of a bread-box. One can start and finish such works before one gets bored with them and they fetch respectable money when they sell. And they are large enough to be thought of as important. Good for the ego, very collectible for the corporate lobby. That I'd like to be able to do with no interruption. But there's always the nagging practicality of making sales, So the preponderance of my work is in pieces smaller than a loaf of bread-mostly animals and birds and small human (mostly female) figures. About 70% of what I have survived on has been those kinds of pieces. The other 30% has been 'larger-than-a-bread-box', in fact sometimes quite massive. It's nice to get a commission for a large public art-work. But such works tend to be better for the ego than they are for the pocketbook. They take a lot of energy and can result in a big-time vexation to the spirit.

SS: Note: George's resume includes "The Builders", a 21'-high composition of large black granite blocks and polished bronze figures located in a Calgary office complex. The commission included doing all phases of construction and installation for a price of $150,000, taking seven months. Among others, he promoted and co-created a multi-figure life-size installation depicting an Eskimo myth of the Sea Goddess Sedna. (George carved the Sedna figure which was seven feet high, carved from a 13,000 lb. piece of Arctic marble,) Three Eskimo carvers created accompanying figures of the animals over which Sedna rules. The pieces were carved at a wilderness marble site near Cape Dorset on Baffin Island (with many difficulties) and then transported to Toronto for installation in the corporate lobby of The Royal Trust Company. Commission price was $230,000.

GP: I am negotiating just now for a large public work which will be similar to an 'inukshuk', which is a structure of natural stones assembled into a human form. These forms are built by Eskimo people in the Arctic and are often used as markers for travel.

We look at the foam models for this potential piece. He has set aside two massive granite quarry-blocks at Quadra Stone's yard, each measuring 20 feet in length. These will be the 'legs' for his inukshuk.

GP: The stone is now in angular blocks, but I want them to look like worn river-stones, akin to the shape of huge french-sticks. My inukshuk will not have a secret, inner meaning. It will simply be a huge, carefully balanced sculpture of great mass and power. And its power will be, in its simplicity, there being only five pieces in the structure.

We look at George's sculptured benches, including one he describes as 'The Palliasse' bench. (Look it up in the dictionary.) At 4' long by 18" wide, it is made to look like a padded blanket or pillow which is flowing like a magic carpet. The flowing curves make it comfortable to sit on at any position. The base block is carved with rippling waves and shadow-lines.

SS: I know you don't profess to have any hidden 'meaning' in your pieces, but what were your thoughts when you were doing a work like 'Shadow Garden'?

GP: I'm not entirely into birds and bears. This work is total fantasy, no one piece being identifiable as a known creature or thing. Each is carved to maximize the effect of texture and shadow and form. Will it sell? I don't know. But in a departure from the eternal practicality of making a living that I have been harping about, 1 feel that I must do it and to hell with whether it sells or not. Not like me.

SS: How did you get into stone carving?

GP: I had worked at various industria I sales jobs. In 1970 I took a job selling high quality business furniture, which opened up the world of design and art for me. It was like being born again. I was surrounded by designers and architects. I learned the joy there can be in simplicity. I met my mentor, E.B. Cox, who was the first stone carver in Canada to work in the scale of the 'coffee-table' sculpture. I became obsessed with his work and his life-style and I pestered him mercilessly to show me how it was done. I carved at every spare moment, learning all I could from E.B. and experimenting with methods of my own. By 1972 I had produced a small collection of very humble little carvings and was encouraged to sell eight of them at a craft show that year. So I worked at it all the harder, eventually spending more time at carving than at my job. I moved to Vancouver in 1975, doing two shows a year at my home for the next 13 years, building up a stable of collectors and getting much better at the craft. Eventually the business built up and 1 took my last regular paycheck from a job in 1979.

SS: How do you see yourself as a teacher?

GP: I seem to know most of the things you have to know to make a sculpture. I don't pretend that I'm teaching people much about art. There are so many good artists in our association. But I carve stone every day and there are not many problems about producing sculpture that I have not encountered. So I have a let to teach people who seek knowledge. I like people who like stone. I'll be at the Cowichan Lake symposium in September and Silver Falls again in the spring.

George seems to embody the notion of "Just do it." He is generous, if opinionated, as well as energetic, very productive and encouraging of others, a fact to which many in this group can attest. He is one of the founding members of the association. He is a regular instructor at our symposia, in which he shares his knowledge of tools, process, and sales. He also occasionally shares articles about tools or carving processes in this newsletter (a collection of which he promises is getting ever closer to being a book for stone-carvers.) Many thanks, George, for all you've contributed!