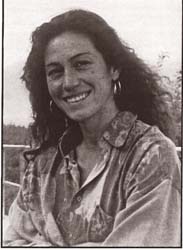

The following is an interview with sculptor Sandra Bilawich, of Victoria, B.C., which took place in late December, 1995. Sandra is a regular contributor to the workings of the NWSSA Summer Symposium. She most recently coordinated, along with Daniel Cline, the Vancouver Island Stone Sculptors Symposium. She is one of those inwardly solid people who seem to live with clarity and purpose. In the last few years, she has focused that clarity on the creation of her sculpture as a full time occupation. Our discussion began while looking through her portfolio.

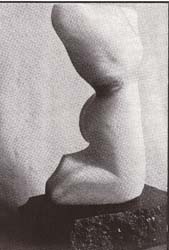

Steve Sandry: Tell me about the first sculpture, "Risk".

Sandra Bilawich: I returned from my second symposium in 1993 wilb a strong desire to try sculpting a human torso. I was feeling lbe need to take more risks wilb life and. by extension, my sculpting. I tried to think of all lbe tbings lbat "risk" meant to me as I worked. I selected Italian alabaster because it is soft, translucent and bruises like skin. Decisions involving risk usually involve running around the waist and up lbrough lbe right breast. This could represent a vulnerability or even scars left from life experiences. The overall figure is strong. with a twist at the waist, suggesting flexibility in dealing wilb life' s changes. The figure IS kneeling to indicate humility .

SS: So, was this a metaphoric piece about your getting into sculpture full-time?

SB: I guess it is. I had been sculpting full-time for a year. The very first day I spent sculpting at my first Stone Sculptors Symposium, in 1992, I felt tired but exhilarated, knowing I was looking forward to doing it more. It was lbe first time I'd done anytbing !bat had "ands" attached to it, instead of "buts". Then it became a matter of figuring out how to make it happen.

SS: How much sculpture had you done prior to 1992?

SB: None. During lbe summer of 1992. I met George Pratt selling his stone sculptures at Granville Island Market in Vancouver. He mentioned an upcoming stone sculpting symposium at Camp Brolberhood. I was working for one of lbe airlines at lbe time, as a technician. On an impulse, I booked my holidays and decided to give it a try. My first day. Myrna Orsini showed me how to hold a hannner and chisel. Everyone I met had so much to share, so open and tactile. It was an incredible experience. and I left feeling like I had found a new family. It reminds you, when you are working alone, how important olber people are.

SS: Do you tend to work long periods alone?

SB: Yes and no. The act of sculpting involves a lot of time alone in the workshop--in isolation. The finished product. lbe sculpture, provokes a reaction and is a form of communication and connection. Communication, interaction and play give me a source of inspiration and feedback which is very important. too. I need to have a balance between lbe isolation and the socialization. Both element,> are important, and help me to learn and grow as a person and as a sculptor.

SS: When you're working on a piece, are you thinking about communicating with people?

SB: Yes. but it is equally important to communicate with the stone, too. I remember once making a maquette for a sculpture lbat I wanted to do. I picked out a stone and began chipping away. Large pieces began to drop off in the wrong areas. I must have looked frustrated, because someone came up and asked me what was wrong. I remember saying, "The stone isn't listening to me. It isn't doing what I want it to." As I listened to myself. I realized I was trying to force my ideas on lbe piece. I had not taken the time to listen and find out what was in the stone. It occurred to me that I would never have tried lbat approach wilb a person. So, after lbat I began approaching my work with more awareness. From the beginning I now see lbere have been layers of "fog" !bat have lifted like little veils. And I'm allowed to see tbings with more clarity each time. The stone and the process of sculpting are therapeutic, like an extended course in communication. If you can communicate with a stone, you can certainly communicate with a person.

SS: As you work in lbe creating process. how do you stay in touch wilb lbe end product which will do lbe communicating?

SB: It changes as I go. Each piece is like a relationship. It grows and evolves as you put energy into it. You can't really define it beforehand. If I'm working on a commission, I try to think about lbe person for whom it is intended. Some of my ideas for sculpture come from stories. I think of a single image that will encompass the important elements of that story. As I work on it, each piece evolves--the ftnished sculpture is never exactly what I first envisioned.

SS: Tell me about your process of making sculpture.

SB: I'm a multi-task person. I like to have four or five things on the go, in order to feel good. T get a clear idea of what I think I want to do, then I start it. Then I start something else. I repeat this process about four times. Once I have all the pieces started, it moves along very quickly. If they are big pieces, I may have only two in process. Sometimes I will go to my metal work to keep playing and creating, yet give my stone carving muscles a rest. When I'm ready, I'll return to the stone and dive right in. But if I'm not ready, that tells me there are things inside me that need direction, or another experience I require.

For me, focus is very important. I'm a fairly spiritual person. Part of my Buddhist practice is to do prayers every morning and evening. They ground me; lbey remind me who I am and what I want to achieve. I go over my dreams and reiterate them to myself. This is where I build my sense of determination and my appreciation. done in lbe form of ritual prayer.

SS: Wherever the inner image comes from, it must be some kind of composite of who you uniquely are.

SB: I trust lbat whatever I am exploring at lbe time is important. However, it is not necessary that people see the same things in the sculpture that I do. Sometimes it will have a different meaning to them. There always remains that unknown element: the sculpture may act as a catalyst for them, revealing something in their lives that needs expression.

SS: I understand lbat you put on several of your own shows per year.

SB: I have done four shows on my own so far. I am discovering lbat my sculptures sell better when lbey are displayed all togelber. One of lbe benefits of your own show is lbat you get to meet lbe people buying lbe pieces and a sense of the sculpture's destination. The pieces are like children; in time, lbey leave to fmd lbeir own place.

SS: Do you keep the pieces around any given length of time before you show or sell them?

SB: I like to enjoy lbem for a while once lbey are finished, but occasionally lbey will disappear as soon as lbey are completed. When lbey're sold, you get to See lbe individual's excitement. I also enjoy it when people call me later to tell me lbat lbey lbink the sculpture is beautiful and how much it means to them.

5S: That sounds like real communication. Why do these objects have meaning to people?

SB: Because we place meaning upon them.

SS: Is it the energy that goes into it? Does this sculpture have an energy that's different than the raw stone?

SB: I think it's like magic. I have learned simple magic such as rope tricks and slight of hand. The whole idea of magic is lbe ability to change consciousness. With stone, people are amazed by how we, as sculptors, fmd something in the stone. I think of my work in stone and metal as taking things people overlook and presenting these materials in a form that they can appreciate. Sometimes, people discover more in a piece than even I have managed to see.

SS: Would you tell us about your history?

SB: I was born in Saskatchewan in 1963. My family moved to the Yukon when I was seven. The natural environment was very close. I was a big daydreamer, and had a good imagination that occasionally got me into trouble. I spent time wondering, "Why am I here? What is my purpose in life?" I was, left to my own devices as a child, and encouraged to pursue whatever interested me. I created fantasy worlds in my head, like parallel worlds. And you had to pass through little doorways in your mind to get to them.

I felt I knew more as a child than I do now. I felt like I was part of the world, part of nature. I was very comfortable being in nature on my own with animals; grizzly, caribou, moose. I felt in tune with nature. It was about people that I didn't have a clue. That was my next big adventure--leaming more about myself by learning more about people.

(Sandra recounts her adult travels and work history which include prospecting in the Yukon. studying geology, doing home renovations, sales in the stock market, working in a gold mine, working as a welder for an airline, and eventually becoming a sculptor.)

This was when I met George Pratt. I burned my boat once I found the shore I wanted to stay on. I quit my job and began to figure out how to make a living as a sculptor. I do not recommend this particular technique for everyone. It has created some challenges.

I've been a practicing Buddhist for the past eleven years. One expression they have is, "When the student is ready, the teacher appears". The teacher isn't always someone obvious. It could be a child, perhaps. who could teach you how to look at things differently. Sculpting is one of lbe things that appeared for me.

I'm also a member of the Soka Gakkai International, a nongovernmental organization associated with the United Nations. This group promotes world peace through education and cultural exchanges.

SS: What about your involvement now with lbe NWSSA?

SB: The Association has provided me with an invaluable opportunity to network with other sculptors, and many other resources--materials, education. The newsletters help me to stay connected wilb people and events. even lbough I am living a little off lbe beaten palb on Vancouver Island. This past year I was able to help organize a new symposium at Lake Cowichan. It was one of those opportunities for growth. I have renewed respect for the NWSSA members who are always so generous with their time and energy. (Sandra also participates in the fund raising auction held at the International Symposium at Camp Brolberhood. )