Why is the Kenya Pavilion Full of Chinese art?

In the last issue of Sculpture NorthWest, we showcased six of our members talking about what they thought made their art their own. That is, how much work must they do to sign their name to it?

In this issue, we are expanding the question to the international scene by covering what is happening at the 2015 Venice Biennale Art Show. Can it be called the Kenyan Pavilion when it is filled almost exclusively with Chinese art by Chinese artists?

The Venice Biennale is one of the oldest and most import exhibitions of contemporary art in the world.

This year Kenya is part of the exhibition. NPR's Gregory Warner reports that there is something odd about the artists who've been chosen to represent that country ....almost none of them are Kenyan.

"Why Are Chinese Artists Representing Kenya At The Venice Biennale?"

There's something sketchy at this year's Venice Biennale — the international art exhibition sometimes dubbed the Olympics of the contemporary art world.

When you come to the Kenyan pavilion, almost all of the artists will be ... Chinese.

The Biennale, one of the oldest and most important exhibitions of contemporary art in the world, takes place in Venice every two years. Thirty countries, including the U.S., have a permanent slot.

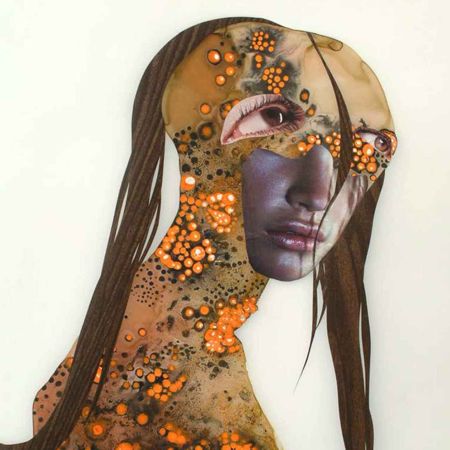

About 50 other countries have applied for their own exhibition space, called a pavilion. The East African country of Kenya hosted its first pavilion in 2013 and plans to host another this year, featuring mainly Chinese nationals. None of them have apparently ever been to Africa or reference it in their work.

About 50 other countries have applied for their own exhibition space, called a pavilion. The East African country of Kenya hosted its first pavilion in 2013 and plans to host another this year, featuring mainly Chinese nationals. None of them have apparently ever been to Africa or reference it in their work.The controversial roster has provoked outrage among Kenyan bloggers and artists. It's also provoked a sense of deja vu — the same thing happened in 2013.

In Nairobi, where the Kenyan contemporary art scene is gaining traction with serious art buyers, the news is being felt not just as an artistic flop but as a colossal missed opportunity. "It's a kick in the stomach," says Sylvia Gichia, director of Kuona Trust, an artist's collective and residency program in Nairobi. Organizations like hers work hard to bring Nairobi's artistic renaissance to a global audience via art fairs and art auctions.

Needless to say she is dismayed that the 370,000 art lovers who visit the Biennale will see none of the work that's driving the contemporary Kenyan scene. "What," Gichia asks, "do the Chinese have to do with visual arts in Kenya?"

Nobody in Kenya's government will answer that question. Calls and texts to the personal cellphone of Nairobi's minister of culture, Hassan Wario, went unanswered. In most countries, the government either selects the artists or assigns that duty to a private gallery. In Kenya, the government apparently played no role other than to fob off the job to an Italian curator, Paola Poponi.

Poponi cannot say she has ever set foot in Kenya, but her official title is "commissioner" of the Kenyan pavilion, the same title she held in 2013. She defended the choice of artists in an email liberal with capitalizations, saying that the Kenyan pavilion ably expressed the international theme of this 56th Biennale, which is All The World's Futures.

Poponi wrote, "Talking about art FROM ANOTHER PART OF THE WORLD during an art exhibition can be useful for KENYA, always more able to create its OWN IDENTITY." She said that art should not be constrained by geography and explained in a follow-up email that "MEETING THE REST OF THE WORLD" would enable Kenyan artists to analyze their own experiences "more deeply."

But if Poponi's goal is to expand the vision of Kenyan artists and have them "meet" the rest of the world, what better way than to invite Kenyans to the Biennale exhibition?

Poponi wrote back to say that the pavilion does feature Kenyans. Two of them. The one ethnic Kenyan in this pavilion — Yvonne Amolo, who has won awards for her film about racism — lives in Switzerland and has no connection to the contemporary Kenyan art scene.

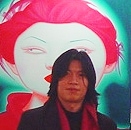

The other Kenyan citizen is a 72-year-old Italian-born painter, sculptor and real estate magnate who has lived in the Kenyan coastal town of Malindi for nearly a half a century. Armando Tanzini sits at the heart of this controversy, because he's the only artist whose work has appeared in both the 2013 and 2015 Kenyan pavilions.

I sat down with Tanzini last week in a cafe in Nairobi to understand how the pavilion had come to be. He explained that if not for his efforts, Kenya would not have any pavilion at all.

I sat down with Tanzini last week in a cafe in Nairobi to understand how the pavilion had come to be. He explained that if not for his efforts, Kenya would not have any pavilion at all."The government of Kenya, they don't know about this important exhibition, the Biennale," he says. "I try several times to help them to understand."

Finally, in 2013, with the government's approval, he paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to get Kenya a pavilion and organize the show. This year he says it wasn't solely his money. He had other private sponsors. But again, no funding was forthcoming from Kenya's government. "Unfortunately, if I want to bring Africa, or Kenya, I must compromise in some way," he said. "Compromise because we have not the money."

Tanzini wouldn't elaborate on what this compromise was, or where the additional money had come from.

A petition circulating on Change.org, titled Renounce Kenya's fraudulent Representation at 56 Venice Biennial 2015, proclaims that "a group of well connected persons, who lack neither the intellectual nor creative capacity to represent Kenya's contemporary art to the international arena, are posturing to the world as the Kenyan Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennial in Italy."

The Biennale would not respond to requests for comment. When the exhibition opens on May 9, participants will have to contend with Kenyan protesters who say they'd rather have no pavilion at all than one that doesn't represent their country. Novelist Binyavanga Wainaina told me that [the] issue is not with the Biennale nor with Tanzini but with Kenya's Ministry of Culture — and it's dismissive attitude toward the arts.

"That this parody could happen two years ago was already far from excusable," Wainaina said. That it would happen a second time, without government comment, he says, is "farcical."

Excerpted from the full text of All Things Considered, March 30, 2015 by Gregory Warner