The Hand That Rocks The Cradle Also Carves The Monuments

Women as Stone Sculptors

Women as Stone Sculptors

By Penelope Crittenden

Who knows when the first woman picked up something sharp and decided to use it to carve an image in stone? The studies of many early ethnographers and cultural anthropologists indicate that women often were the principal artisans in the cultures considered as Neolithic, creating their pottery, textiles, baskets, and jewelry. However, no mention is made of stone carvers at this point.

The earliest three-dimensional public artworks made by women were wax figures. These were life-size clothed effigies for which women modeled the hands and heads, hyper-realistically, in wax. (The clothes were, probably, made by women too, but there is hardly any research on this yet.)

Women built a specialist tradition in wax modeling, going back at least as far as the Middle Ages, when nuns made candles, flowers, and statues of saints in wax. In America, Patience Wright (1725-1786), who had not only a talent for art but a talent for self-promotion as well, is usually credited with being the first professional woman sculptor.

Patience began modeling in bread dough and local clay. Widowed early, she turned her hobby into a means of support. Wax was readily available from candle makers and required no tools or training to use. Capitalizing on her talent and forceful personality, she began a traveling wax works show, moved to London, met Benjamin Franklin, was received by and modeled portraits of the king and queen, and became a legend in her own time.

During the eighteenth century, a number of enterprising women, took up wax modeling, among them Marie Grosholtz (1761–1850), later known as Mme Tussaud. These women specialized in waxworks of prominent contemporaries, and some even traveled from city to city in order to show their homemade, but very popular collections of waxworks of prominent contemporaries to the local public for a fee.

Such work, which continued through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, all suggest the sculptural back doors through which eighteenth-century women artists entered the domain of public sculpture.

In wasn’t until the mid-1800s that a new generation of women stone sculptors emerged. Going against the accepted role of wife and mother, these women were often ridiculed and ostracized. The lucky ones had the financial and emotional support of their families and the private means to afford materials and formalized training.

In America, women could attend academies such as the National Academy of Design and the Art Students League in New York, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

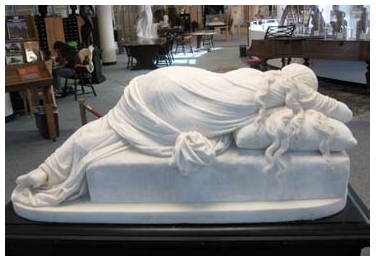

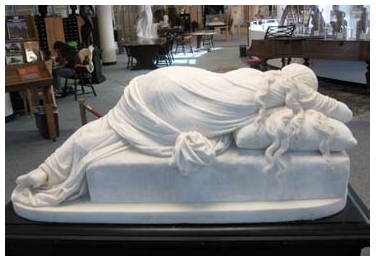

Many others, however, chose to study in Italy and established studios there, taking advantage of the company of stone carvers and craftsmen as well as the ready supply of white statuary marble. These artists worked in the prevailing neoclassical style for their monuments and commissions. The first “school” of women sculptors arose around Romebased Harriet Hosmer (1830-1908), Anne Whitney (1821-1915) and Edmonia Lewis (1844-1911.)

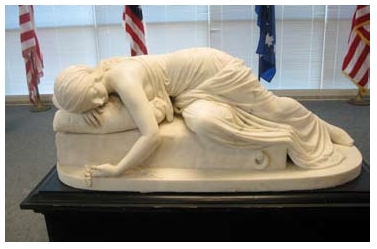

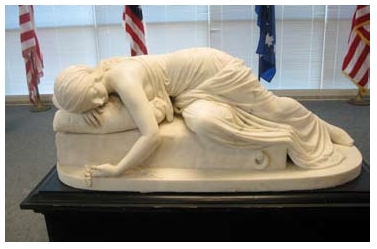

Harriet Hosmer began her life in Watertown, Massachusetts and from an early age was often to be found in a clay pit near her home “modeling horses, dogs, sheep, men and women.” Her high spirits and strong will earned her expulsion from school not just once but three times. After school she decided to pursue sculpture in earnest. Although her father encouraged her, the rest of Massachusetts was not so understanding. Even her friend Nathaniel Hawthorne despaired over her unmarried state and her “jaunty costume” which consisted of a “sort of man’s sack of purple broadcloth, a male shirt, collar and cravat and a little cap of black velvet.” Fortunately she came from a supportive family who enabled her to go to Rome and study. Even though her “Beatrice Cenci”(1857), was a triumph at the 1857 Royal Academy exhibition in London, she nevertheless still had to deal continually with rumors that one or another of her male associates did her work. Slander and prejudice dogged most of her career.

Anne Whitney (1821-1915), also from Massachusetts, was driven by a passion for social justice and many of her sculptures reflected her social sympathies. Her colossal “Africa” (1864, destroyed) embodied antislavery sentiments in an idealized neoclassical form. Experiencing much of the same prejudice that Harriet Hosmer faced, and with a similarly supportive family, Anne too went to Rome where she was one of several young American women sculptors who went to work there among their male colleagues.

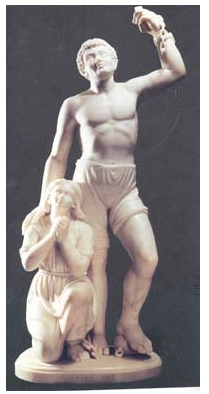

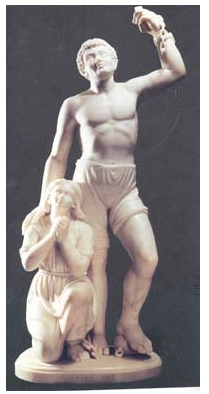

Edmonia Lewis (1844-1911) had not only to struggle with prejudice against women sculptors, but also against her mixed black and Chippewa heritage. After school she went to Boston, the center of liberal thought at that time, and began studying with Anne Whitney. Eventually, she too went to Rome to study, there creating life size marble works celebrating emancipation and her Indian heritage. Although some feel that her work lacks the conventional polish of some of her contemporaries, her passion, expressiveness and ethnic content have great appeal. Her life-size marble “Free At Last” powerfully symbolizes the emancipation of black people. Lewis said that she was expressing her “strong sympathy for all women who have struggled and suffered.” Refusing to be stopped by racism or the patronizing attitudes of her times, she became the first major black sculptor in America.

Edmonia Lewis (1844-1911) had not only to struggle with prejudice against women sculptors, but also against her mixed black and Chippewa heritage. After school she went to Boston, the center of liberal thought at that time, and began studying with Anne Whitney. Eventually, she too went to Rome to study, there creating life size marble works celebrating emancipation and her Indian heritage. Although some feel that her work lacks the conventional polish of some of her contemporaries, her passion, expressiveness and ethnic content have great appeal. Her life-size marble “Free At Last” powerfully symbolizes the emancipation of black people. Lewis said that she was expressing her “strong sympathy for all women who have struggled and suffered.” Refusing to be stopped by racism or the patronizing attitudes of her times, she became the first major black sculptor in America.

Edmonia Lewis (1844-1911) had not only to struggle with prejudice against women sculptors, but also against her mixed black and Chippewa heritage. After school she went to Boston, the center of liberal thought at that time, and began studying with Anne Whitney. Eventually, she too went to Rome to study, there creating life size marble works celebrating emancipation and her Indian heritage. Although some feel that her work lacks the conventional polish of some of her contemporaries, her passion, expressiveness and ethnic content have great appeal. Her life-size marble “Free At Last” powerfully symbolizes the emancipation of black people. Lewis said that she was expressing her “strong sympathy for all women who have struggled and suffered.” Refusing to be stopped by racism or the patronizing attitudes of her times, she became the first major black sculptor in America.

Edmonia Lewis (1844-1911) had not only to struggle with prejudice against women sculptors, but also against her mixed black and Chippewa heritage. After school she went to Boston, the center of liberal thought at that time, and began studying with Anne Whitney. Eventually, she too went to Rome to study, there creating life size marble works celebrating emancipation and her Indian heritage. Although some feel that her work lacks the conventional polish of some of her contemporaries, her passion, expressiveness and ethnic content have great appeal. Her life-size marble “Free At Last” powerfully symbolizes the emancipation of black people. Lewis said that she was expressing her “strong sympathy for all women who have struggled and suffered.” Refusing to be stopped by racism or the patronizing attitudes of her times, she became the first major black sculptor in America.In the early 1900s, although it was still considered odd for a woman to choose sculpture as a vocation, more and more women became accepted. One of the most respected and influential, was the renowned sculptor of animals, Anna Hyatt Huntington (1876-1973.) “Animals have many moods and to represent them is my joy.”

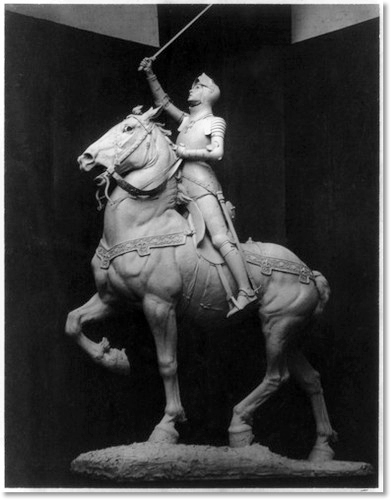

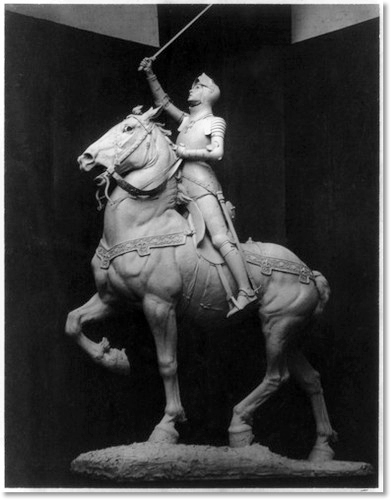

Anna broke new ground for women sculptors. Her bronze “Joan of Arc” (1915) was the first equestrian statue by a woman. Independent of spirit, her formal training was short and she could often be found at the Bronx Zoo, “a tall young woman in a tailor-made frock and red plumed hat, doing a clay study of a bison.” Although she had no plans to marry, she finally accepted the repeated proposals of wealthy philanthropist Archer Huntington. Now, with unlimited financial resources at her disposal, she was able to work on a larger scale and support the work of other artists. The Huntingtons were responsible for the founding of fourteen museums and four wild life preserves. The most famous of these being the 9,000 acre Brookgreen Gardens in South Carolina founded by Anna and Archer in 1931. Originally intended as a setting for her sculptures, she soon commissioned works from her friends and it eventually developed into this country’s first public sculpture garden and has the world’s largest collection of figurative sculpture by American artists in an outdoor setting.

Little by little, prejudice against women as sculptors grew less adamant and by the late 20th century there were many successful women stone sculptors. Cleo Hartwig (1911-1988), Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975) and Jane B. Armstrong) b. 1921) to name only three.

Coincidentally, or not, sculpture by women was more prevalent during the Suffrage Movement of the latter part of the 19th Century and the early 1900s. But in post-war America, around the 40s, the image of woman as homemaker seemed to take over and it wasn’t until the feminist movement of the 1970s that acceptance of women in new fields began to be seen again.

It has been a long slow ascent for women as sculptors. Starting in caves making household crafts and goddess worship paraphernalia, they were denied anything much more than that until a few began modeling figures in wax to make a living with traveling displays. With a few lucky breaks and access to some money, a handful of women went to Rome where they began producing world-class art, allowing them to finally force their way into a man’s world and produce their own renaissance.

This issue of Sculpture NorthWest is dedicated to women in every country who for generations have struggled to follow their muses and create their magnificent art that we see throughout the world today.