Sculptors from the Past: The Piccirilli Brothers - March/Apr 1996

- Details

- Created: Friday, 01 March 1996 22:23

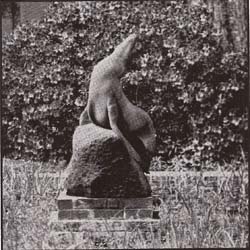

Three brothers from Italy become outstanding sculptors in the USA

When Giuseppe Piccirilli and his wife, Barbera (Giorgi) came from Massa, Italy to New York in 1888, they brought with them traditional European stone carving skills and the ability to work as a group. With six sons, Piccirilli established a marble cutting studio which not only carried out designs for others, but also contracted independent sculpture work. Three of his sons, Attilio, Furio and Horatio became creative sculptors. Attilio and Furio both attended the Accademia di San Luca in Rome. Horatio was a small boy when the family left Italy.

Attilio headed the family studio and like his brothers Furio and Horatio, he shared the responsibility for many of the family's sculpture commissions. In 1889, Attilio made his debut as an artist with the McDonogh Monument in New Orleans, a portrait statue on a pedestal of a boy and girl bringing flowers. Atti1io won the contract for the Maine Monument in 1901. This ambitious undertaking, which he worked on for ten years, is placed at one of the entrances to Central Park. It is a tall python preceded by the prow of a ship, with groups of figures around the base and at the top, Columbia in a shell drawn by sea horses. Attilio completed numerous commissions throughout the United States and won many awards including the Gold Medal of the Academy of Design in 1926, again in 1928, and the grand prize for sculpture at the Grand Central Art Galleries the following year. The sculptor's achievements were rewarded with a gold medal at the Panama-Pacific Exposition, and in 1932, the Jefferson Presidential Medal was bestowed on him in recognition of his service as a United States citizen. Attilio Piccirilli died in New York on October 8, 1945.

Furio Piccirilli was born in Massa, Italy on March 14, 1868. Furio was considered the most creative and the best modeler of the family. In 1920 he designed the sculptural decoration of the Parliament House, Winnipeg, Canada. The designs included a seated statute of Pierre Gaultier de Varennes in elaborate eighteenth century costume. A statue of Murillo was sculpted for the Fine Arts Gallery, San Diego. Various religious works and numerous animal studies were made over the years. In 1921, Furio went to Rome and married his cousin. After a few years, he returned to New York and planned to remain there permanently. Hoping that the climate would be better for his son's health, he returned to Rome in 1926 where he remained until his death in 1949. He was a member of the National Academy of Design and an associate of the The Architectural League of New York.

Horatio Piccirilli, fifth of the famous sculptor brothers, was born in Massa, Italy, on June 21, 1872. He learned his profession in the family studio, as well as by studying with a French sculptor active in New York, named Edourad Roine. Horatio worked on numerous architectural projects for the Piccirilli studio, including the Riverside Church and Saint Bartholomew's Church, both in New York City. He also worked on the state capital building in Baton Rouge, Louisiana and the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. With the few independent works that were his own creation. Horatio abandoned all rememberance of past styles and worked in a spirited impressionistic style. After the death, in rapid succession, of the other brothers, the studio closed in 1946 and Horatio retired. He died on June 27, 1954.