- Details

-

Created: Thursday, 02 March 2000 05:55

Several years ago, NWSSA initiated a “Statement of Services” that is used for vendors and members who are paid for their work. Generally this agreement is used at our symposiums, such as Camp Brotherhood. It states the project, the name of person and the description of the services offered, the rate and method of payment, the estimated completion time and is signed by the provider and a member of the Board of Directors of the Association. This agreement serves two major purposes: each participant knows what is expected…and the association is protected in case of audit. If the IRS inquires about a particular payment, our Treasurer can produce the signed and approved agreement. This is a contract.

What is a contract? A contract is an agreement, whether oral or written, whereby two parties bind themselves to certain obligations. In order to be valid there must be an offer, acceptance and the concept of “consideration.” Consideration is the inducement to a contract or other legal transaction. This can be an act or the promise to act given by one party in return for the act or promise of the other.

Why is it needed? To protect or limit financial involvement, control risk, to comply with commercial law, to assure that work is accomplished in an agreed to manner. The list goes on and on! And remember, negotiating terms that are fair to both parties is essential if you want to get paid and maintain a cordial relationship with your clients.

“Government contracts tend to be specific about payment schedules,” says Craig Mengel, president of Multimedia Works Group, Westport, Conn. “You have to take that into account with your budgeting—you’re not going to change it.” Some government contracts pay only 5 percent to 10 percent up front, while the rule in the corporate world is one-third to one-half. After the initial payment, you’ll most likely get half of the balance in the middle of the project, with the remainder upon completion. Tying payment to your schedule helps, Mengel says. “If delays start creeping in, you can deal with those according to your progress agreement”, he explains.

Why write a contract? If some contracts don’t have to be in writing, why are we writing them? Good question and an important point. We are putting them in writing because we want a record of the true agreement. If you think that means that you’re concerned about people changing their mind or having a different recollection of events, you’re right. People hear what they want to hear and believe what they want to believe. A good contract spells out how a project should proceed and what type of product the client expects. It also sets deadlines and specifies the amount of advances, royalties and other support, such as the provision of materials, studio workspace, tools, assistants and who does what … and when.

When is it needed? Obvious occasions are in the purchase of products; enforcing warranties and guarantees; in employment and providing of services. It also serves to provide a third party, such as an arbitrator with information as to an agreement.

Another purpose of a contract is to control overlooked or unforeseen conditions. Michael Heiser, under a municipal arts grant, installed a monumental granite sculpture, “Beside, Against, Upon” at the Myrtle Edwards Park on the Seattle waterfront. The work was designed to fit within the budget of the grant with additional funding by the artist. However, in carrying out the project it was found that the structure could not be completed without a professionally designed and approved structural foundation. Tons of concrete and reinforcing steel were not in the original proposal. The only solution was to quit the project (most of the funds were already used on the acquisition, shaping and delivery of the massive granite pieces) and pay back the funds, or provide the additional funding.

Clearly the grant was a contract and certain rights and responsibilities were spelled out. But some important factors were not, i.e. local building code enforcement, professional engineer design costs, use of a licensed contractor with union labor and what would happen in regard to a crippling cost overrun. In the end the project was completed but the final design was compromised from its original vision and the artist paid heavily from his own funds.

\\

Five essential elements of a contract:

1. Identify the parties by name: And to help in identification, it is also customary to give the parties’ addresses, but this is for clarification.

2. Consideration for the contract: Sometimes the consideration will be money, but that does not have to be the case. What is important is that there is something mutual between the parties and that it is acknowledged in the agreement.

3. Terms of the agreement: This is the main part of your agreement. State in as clear a fashion as possible what the parties are agreeing to.

4. Execution: It would seem clear that the contract should be signed, but things get confusing when you have agencies, corporations and partnerships. A good rule of thumb is to get everyone on the other side to sign.

5. Delivery: Even though the contract is signed, unless you deliver it and it is accepted before the work begins, you don’t have a valid contract.

If you truly can’t afford a lawyer, ask that your client start with a standard contract, and change it to fit your project’s specifics. There are several excellent on-line support sites with legal forms.2, 3 (See References.) But above all, if there is significant liability, try not to go it alone. The Washington Lawyers for the Arts and Artist Trust offer “The Arts Legal Clinic”, a 30-minute consultation with a lawyer specializing in law for artists and arts organizations. The clinic is offered every second and fourth Monday of each month from 6:30-8:30 pm. Call 206- 328-7053 for appointment.

References:

1 This resource is (c) 1995 by J.W. Dicks, and is excerpted from “The Small Business Legal Kit” published by Adams Media Corp.

2 FREE legal forms, contracts and agreements: www.smartbiz.com/sbs/arts/sbl1.htm

3 Labor Standards for the Registration of Apprentices: www.legalresource.com/legalforms.htm

Resource list:

The Complete Guide to Nonprofit Management, Smith, Bucklin & Associates

Basic Contracts: www.doleta.gov/regs/fedregs/notices/96_19989.htm

Comprehensive Resource for Sculptors: www.sculptor.org

- Details

-

Created: Thursday, 02 March 2000 05:25

In November I traveled to Quebec to attend a conference. On the way, I stayed overnight in Toronto, where I met with a potential agent and visited the Art Gallery of Ontario. In 25 years of living in Canada, I had not seen the permanent exhibition of Henry Moore’s large plasters there, although I had read an excellent account of it in R. Berthoud’s The Life of Henry Moore (1987. Dutton). I was a bit skeptical of a roomful of plasters, though. I had seen a large retrospective of Moore’s bronze sculptures and wooden carvings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, seen many of his large bronzes in various cities, and regularly enjoyed books and photographs of his work in my own home. Last spring I spent an afternoon with a tall Moore bronze in the courtyard of my brother’s kitchen on an olive oil ranch in California. What more could a roomful of plasters add to all that? They added a lot, I want you to know, and I’ll try to show you how.

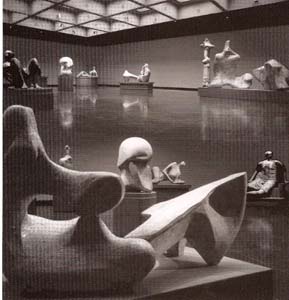

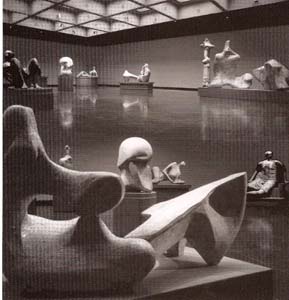

First are the obvious things that everyone expects in every exhibition. And this exhibition satisfies them all superbly (Fig.1). There is lots of great art (132 sculptures and 73 drawings at the AGO; 900 Moore works in all). The plasters are displayed thoughtfully in a large, well-designed space, with lots of room between them, under an interesting combination of artificial and natural light. When so many good pieces are arranged in such interesting ways in relation to each other, the collection as a whole affords many opportunities to explore relationships among forms from different viewpoints. And when they are all by the same artist, the effect is stunning. When I visited there were so few other people that I felt alone with Henry Moore and his work. The overall effect at the time was that nothing else in the world existed for me but those forms.

Although there are fewer of Moore’s sculptures in Toronto than of Brancusi’s in Paris, fewer than of Milles’ in Millesgården, and fewer than of Ng Eng Teng’s in Singapore, this still must rank among the world’s best collections of work by a single sculptor, and all of it in this room is massive. In addition to the plasters, there are at least five other Moores in other rooms in the Gallery, in a both bronze and wood, and an enormous walk-through bronze piece on the street corner outside. Even without so much of his other work nearby, seeing so many of Henry Moore’s sculptures in the same room was something I will never forget, and I recommend it to anyone.

Those are the obvious things, and they alone would make for a memorable experience. Surprisingly, though, the best things for me were that the pieces are all in the same medium and that they are of plaster. These two factors conspire to emphasize form, and form is what I experienced. More than that, I experienced a family of forms, imagined and executed at different times in the life of a great sculptor. Because plaster is wonderfully responsive to light, it affords an exquisite sense of form. When it is well lighted, the scale of light intensity ranges from pure white highlights to pure black shadows, and the jump from white to black at edges is sharp. Highlights, shadows, and the range between them all vary wonderfully, both directly and in reflections on the floor. The exhibition is brilliant, literally. The sculptor, the architect (and his assistant, Henry Moore), and the curator (with Henry Moore) saw to that.

Another thing that greyscale did for me in this show was to enhance the effect of tool marks. Much more than I have ever experienced with bronzes, tool marks really did it for me in Toronto. Often, especially with Moore’s massive works, his tool marks are swamped by the scale of the sculpture and overpowered by the smooth, tense surfaces that loop through space on greater-than-human scale, dominating them and making them appear more as scratches than as design elements. But not with the plasters. There can be no doubt about the tool marks on them. They record, on human scale, intentional movements of Moore’s body as he worked. Over the decades since Moore made the plasters at his country home in England, including the 25 years they have rested together in one room in Canada, everything has acquired patina. Some plasters are still nearly white. Most are one or another shade of ivory, much more white than yellow. But the scratches are dark, stained with dirt from the English countryside, with urban dust from Ontario, and perhaps with a bit of oil from Moore’s own hands.

The fact that each piece is lighted both naturally and artificially modulates the power of greyscale to evoke a sense of form, lending even more power to perception. The grey autumn morning bathed the exhibition in a soft, spectrally white natural light, through at least a hundred large, flat, frosted skylights recessed deeply into the ceiling in quartets (Moore himself designed this feature). More subtly because of the relative brightness of the sky under that day’s conditions, a warmer artificial light also bathed the plasters from somewhat different angles. This illuminated each piece by lights of slightly different colours at the same time, modeling it in two ways at the same time (it would be interesting to view a plaster in Terry Kramer’s light box under two colours of lights).

Someone once told me that all sculptures should be white. Sculpture is about form, she said, not colour, and only white, featureless media can provide full light intensity gradients or full modeling of form. I resisted that dictum at the time. I was into wood, fascinated by the ability of its laminar structure to enhance form, and I lusted after banded stones for the same reason. Much later in Rome, surrounded by literally thousands of pure white marble sculptures from every century, I began to appreciate it. In Toronto, the lesson really soaked in and I got it.