- Details

-

Created: Saturday, 01 January 2000 23:51

Soon I will have been quarrying sculpture stone for 10 years. I have been threatening to quit the business and get a “real job” for many years; although I have come very close to this goal, somehow it has not materialized yet. Most of the time that I have been collecting stone, I have been attending university during the winter and collecting stone during the summer. Upon graduating, I began to dream of a nice comfortable job sitting in front of a computer all day, free of aching joints, sore muscles and those nice black fingernails that result when they get caught in a collision between two boulders.

Each summer during years that I was attending school, I was faced with the same challenge - fill orders that had piled up all spring, and prepare for the symposium. After the symposium, I worked madly in the last days before I returned to school to get enough stock to meet orders during the winter. This year it was a different situation. After an enjoyable but very busy symposium, I had originally planned to meet any remaining obligations for stone that remained, and then spend a few weeks exploring areas I never had time to go to during my busy summers. I believed that after this was finished I would then be free to leave on my regular annual trip to Japan, but this time with the intention of pursuing a job offer with a computer services/contracting firm. However, as usual, things did not turn out as I expected; I ended up on a trip that was much more than planned. From this expedition I will share a couple of days’ adventures. The best part of this job is finding the stone for the first time, assuming that I don’t have to wander in the wilderness for days searching ( “... just go about 20 or 30 miles up the logging road, stay left and then you will come to a smaller trail heading off that ... well, that’s how it was when I was there about 5 years ago … I think …”) The setting of each location is different and each geological occurrence of the stone has its own uniqueness. After I’ve discovered the stone, most of the work from there on is pure physical labor.

One of the places that I enjoyed discovering on this trip was a wonderful gypsum (alabaster) deposit. I was originally searching for this deposit because I had heard that it could be another source for anhydrite. As it turned out, there was no anhydrite, but there was a beautiful white alabaster that turned to pink and then to a wonderful orange as the deposit got deeper into the ground, mixing with olive green and dark rust colored clays. At first I wandered around a large area looking at samples of the stone and was disappointed at the quality of most of what I saw. After a long exploration, I came across a cavity in the ground, known as a sinkhole, that commonly occurs where there are gypsum deposits. I believe this is caused as salts and gypsum are dissolved and washed away by groundwater or rain. I explored a little deeper into the sinkhole, which is somewhat like a very small cave, but is entered from level ground. I could see the walls worn smooth by years of moisture and water running down from the surface. Covering the tops of the stones and the floor area was a layer of fine sand. I saw a few small protruding stones on the floor and reached down, pulled on them, and they moved, indicating that they were loose. I dug away at the cool damp sand revealing many individual boulders from about 25 to about 100 pounds each, that had either been sculpted and worn smooth by many years of water, or possibly could have been formed from mineral rich water deposits, creating unique natural shapes. I loosened as many as I could and carried them one by one up to the ground level, where I found that upon cleaning the stone further that many of these unique pieces had a wonderful translucency. After taking all of these natural shapes that I could find, I searched the area more. I was pleasantly surprised to find another zone of quality stone near the same area that grades from white into deeper colors, where I could remove good sculpting stone in large blocks using equipment.

Not all stone collecting can be enjoyable as this, as there are many dangers, and bad weather always makes collecting difficult. Also, due to the nature of stone quarrying, large and expensive equipment is sometimes needed, and the location where it is needed is usually very far away from where this equipment is kept. This often makes the cost to bring in equipment far too expensive, and I end up doing the work by hand. A very expensive situation occurred on my trip when I hired a truck to work at a mountainside location where there was a beautiful lilac purple and bright green mottled marble. Access to this location was by 50 miles of paved road, 20 miles of good logging road, and then another 20 miles of poor logging road - a long way from town. As I did not want to take many trips with a small pickup truck I asked around and somebody told me about a guy who owns a big truck with a hydraulic loader that is used to pick up old cars and other scrap metal. Even though it was not anything like his regular line of business, I convinced him to come with me up the mountain to pick stone. Though the cost of hiring him was relatively expensive (over 1 dollar per minute), I thought it would still be more efficient and cheaper to hire him for the afternoon than for me to make many trips over a period of days. As we slowly plodded along the mountain trails I thought about how much this was costing me with each passing minute. Upon arrival however, I was relatively pleased as he picked up small boulders, some weighing over 1000lbs, with great ease, dropping them in the box of his truck. All went well and we pulled out with a good-sized load of stone. We managed to go only about 1 mile when we got to a small patch of road about 25 feet long that had been washed out during the summer when a small beaver dam broke and had been repaired with sand from a nearby hill. Coming in we had really never paid attention as this section of road which was downhill leading in, but when returning, the now loaded truck had to push us uphill to get through this difficult area. The truck hit the middle of this section, slowed down, and then gave an awful shuddering as the back wheels, with about 20 tons of weight from the huge truck and its load, dug down into the loose sand, becoming firmly embedded. With no way to get the truck out, and being too far from the nearest town to contact anyone on the radio, we decided our only hope was to walk out, a difficult and painful thing to do with our heavy work boots. As we plodded along I mentally calculated how long it might take to walk a 20 or 30 mile trek off this mountain, and how big my blisters would grow to be. After what seemed like an eternity, but was actually only a couple of hours of walking, we heard the roar of an engine behind us and were very luckily picked up by a couple of hunters traveling on an otherwise deserted road. They took us into town where we were able to contact the driver of a semi-truck sized tow truck who would make the trip out there (at $100 per hour) to pull the truck out. I stayed overnight in town and waited patiently before calling to ask the outcome of our situation. I was shocked to hear that when they tried to pull the truck out, the soft sand started to give away underneath the truck as it slowly started tilting sideways, threatening to topple over the bank. As a result they had to return to town to get a large backhoe and a flatbed truck to carry it. At the end of the day they were able to dig the truck free and then pull it out using the tow truck, to the great relief of the truck driver and myself. Needless to say the final bill for all of this was huge. Though it is arguable that it may not be my responsibility to pay for the truck driver’s problems while transporting my goods, in the spirit of fairness, we worked out a cost-splitting deal where the only winners were the owners of the other expensive equipment.

When dust settled (quite literally) from this trip, I had been away collecting for over two months without a visit home, and ended up with over 50 brand new types of stone to add to my collection. After returning this week, I will again venture out from Vancouver, for the first time driving half way across Canada to follow up on some good leads, all the while trying to keep a step ahead of the snow. The result of my first expedition was successful beyond imagination. I discovered

new sources for soapstone, alabaster, multicolored limestones, deep pink, purple, red, orange, green and even a stunning deep blue marble, as well as some unique purple and some green gemlike stones, to mention only a few. My body has also gained a few more aches and pains that were not there before, but when the big flatbed trucks come rumbling in with my load of newfound stone I feel a sense of accomplishment. Well, maybe “the job” can wait a few more months….

- Details

-

Created: Saturday, 01 January 2000 23:31

Two years ago, with a book on sculpture gardens of the nation in hand, my husband, Patrick, and I embarked on a six-week adventure across the country. Our first stop was the University Sculpture Garden in Lincoln, Nebraska. Next were the Henry Moore collection in Kansas City, and the Laumeier Sculpture Garden in St. Louis. We crossed New York state on Route 17 as the maple leaves were changing color in the crisp fall weather. The call of the returning Canada geese punctuated our visit to Storm King and Kykuit, the Rockefeller collection. Among the many New York sculpture parks, the Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum is a dream come true! The museum, which opened in 1985 in Queens, brings together over 200 of Isamu’s finest sculptures. The scope of 60 years of intense sculptural activity is in view at a single location.

Isamu bought a photoengraving plant in 1975, a triangular space produced by dividing a city block diagonally. With the help of long-time friend, architect Shoji Sadao, Isamu designed an indoor/outdoor garden gallery. Windows are open permanently to the elements, and unexpected trees growing within add an element of surprise to the space. The garden reveals Isamu’s passion for nature and his desire to sculpt “space.” He effectively used Japanese elements while imprinting his own innovative expression on the garden. Where a traditional tsukuban collects water, his dispenses it. While Japanese gardens often contain stone in its natural form, Isamu displayed chiseled planes and textures and called them “bones of the earth.” White birch, black pine, juniper, katsura, ilanthus, magnolia and various bamboo contribute to an exquisite garden. Stones sculpted into irregular forms add a metaphor of his experience in the world. Ideally-placed voids balanced with solid mass, areas of smooth and rough, geometric and organic shapes — all express design perfection. He intended the stone to reflect the human condition and regarded stone as a source of consolation through its symbolic force of eternal variety.

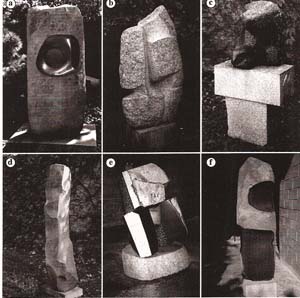

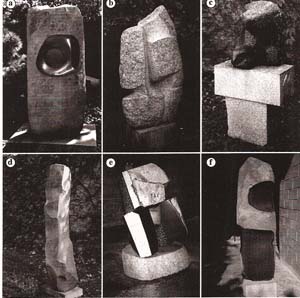

Outstanding in the garden, Core (Fig.1a), is a 74" basalt sculpture on a granite base. Concerning this sculpture, Isamu reflected, “Sometimes out of despair when we have given up, the stone itself sends a message bit by bit. Finally everything falls into place with a precision so remarkable, it cannot be chance.” Of Indian Dancer (Fig.1b), a 60" pink granite sculpture, Isamu said, “ I was reminded of Balasarawathi, the great dancer of Bharatha Natyam whom I saw in Madras. With time, Indian Dancer has also gained the authority which was characteristic of her.” Seeking (Fig.1c), a 29" granite, “refers to the artist and also to the sculpture as an identity. What is its intention? Reflected is the difficulty and uncertainty of its making — its final resolution or catharsis.” Dance (Fig1d), is an 84" Manazura stone carving about which Isamu wrote, “carving follows the possibilities inherent to the stone. This collaboration is limited, but the other way is confrontation. Confrontation may lead to conquest, conquest over oneself, of course, not the stone. Art is more than a compromise: to override the inhibitions that blind.” Woman (Fig.1e), a 66" basalt , was “an abandoned sculpture suddenly come back to life,” he wrote. “Its true nature revealed, it now has left no doubt as to what it must be. My every decision came with an inevitability. An overcoming of hesitations.” Of Sculpture Finding (Fig.1f), a 77" basalt, he reflected “...the presumption to work as we do, comes from the ability of new tools to incise our will upon matter - like a meeting from the opposite ends of time to resume on another level the continuity that has gone on for years.”

On the first floor of the gallery, with its concrete floors and walls, beams of light peer through open windows, illuminating many of his larger sculptures. Heart of Darkness, a large black obsidian, its matrix of white skin and intense, gorgeous black interior, is transformed by the touch of Isamu. Nearby is To Intrude on Nature’s Way, superbly positioned on a wood/granite base. Isamu said “The art of stone in a Japanese garden is that of placement. Its ideal does not deviate from that of nature except in providing a heightened appreciation. Any man-made divergence is carefully hidden, as by the intercession of time and age, nature’s accidents and residue. But I am also a sculptor of the west. I place my mark and do not hide. The cross currents eddy around me. In To Intrude On Nature’s Way, the contradictions between the eastern and western approaches are resolved with a minimum of contrivance.”

The second floor, up wooden stairs, is an exquisite space with warm maple floors, skylights, and a feeling of floating. It houses Isamu’s smaller sculptures in stone, metal and wood. These smaller scale pieces evoke a more intimate response, but remain true to Isamu’s major themes: reference to and reverence for natural phenomena. For example, in Black Hills, the importance of landscape; in Seeker, variation; and in Vertical Man, the figurative presence. This space houses his early works which were influenced by Brancusi’s ceramic and metal sculpture. Also shown are Isamu’s sculptures based on Japanese culture, as well as his surrealist-inspired marble, slate and wood sculptures created during his self-imposed internment period in WWII. In addition, here is a replica of Isamu’s studio in Japan, models for his playground and garden designs, stage sets for Martha Graham and the Akari Lights of Gifu.

Until an opportunity arises to see the garden, the book The Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum (I. Noguchi. 1999. Abrams), is a well produced substitute for a personal visit. [Editor’s note: The biography Noguchi: East and West (D. Ashton. 1992. Univ. Calif. Press) is excellent.] I came away changed, humbled by Isamu’s lifetime achievements, energized and educated by his sense of design, and with a new respect for material and his brilliant treatment of bases. Most of all, I was awed by his unending and uncompromising search for the truth.