- Details

-

Last Updated: Friday, 26 February 2021 01:52

Introduction: Women as Sculptors

Who knows when the first woman picked up something sharp and decided to use it to carve an image in stone? The studies of many early ethnographers and cultural anthropologists indicate that women often were the principal artisans in the cultures considered as Neolithic, creating their pottery, textiles, baskets, and jewelry. However, no mention is made of stone carvers at this point.

The earliest three-dimensional public artworks made by women were wax figures. These were life-size clothed effigies for which women modeled the hands and heads, hyper-realistically, in wax. (The clothes were, probably, made by women too, but there is hardly any research on this yet.)

Women built a specialist tradition in wax modeling, going back at least as far as the middle Ages, when nuns made candles, flowers, and statues of saints in wax. In America, Patience Wright (1725-1786), who had not only a talent for art but a talent for self-promotion as well, is usually credited with being the first professional woman sculptor.Patience began modeling in bread dough and local clay. Widowed early, she turned her hobby into a means of support. Wax was readily available from candle makers and required no tools or training to use. Capitalizing on her talent and forceful personality, she began a traveling wax works show, moved to London, met Benjamin Franklin, was received by and modeled portraits of the king and queen, and became a legend in her own time.

During the eighteenth century, a number of enterprising women, took up wax modeling, among them Marie Grosholtz (1761–1850), later known as Mme Tussaud. These women specialized in waxworks of prominent contemporaries, and some even traveled from city to city in order to show their homemade, but very popular collections of waxworks of prominent contemporaries to the local public for a fee.

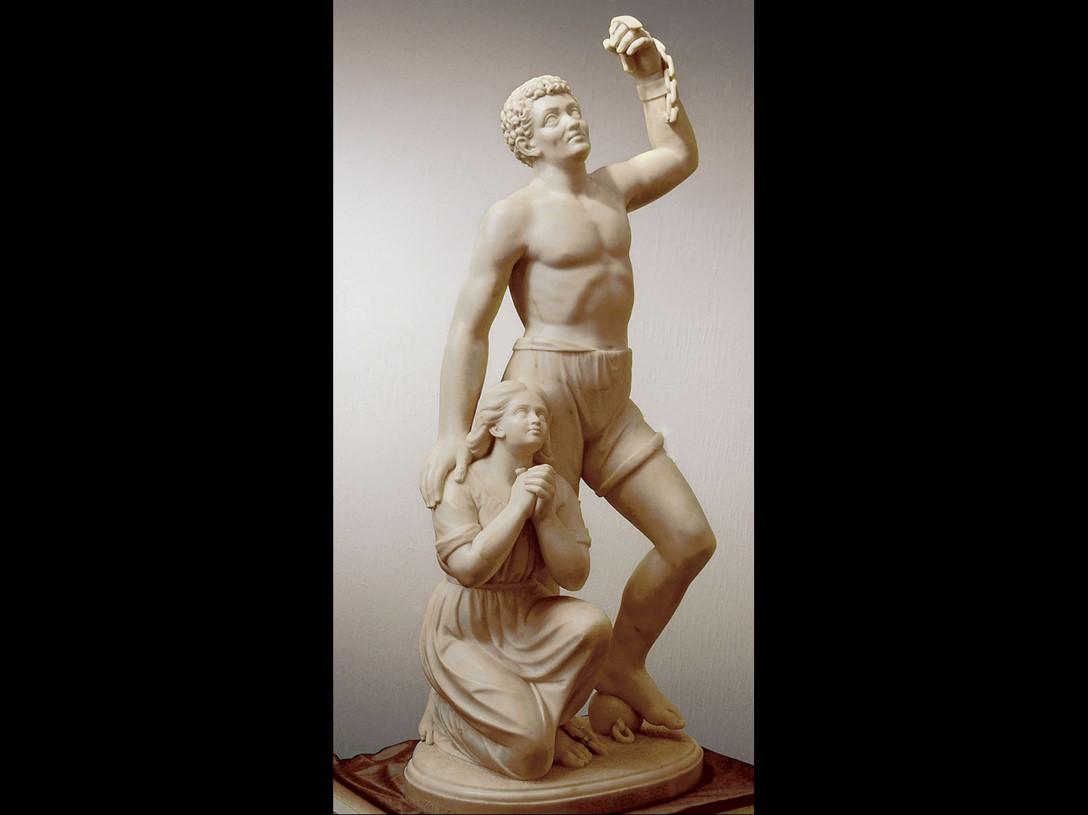

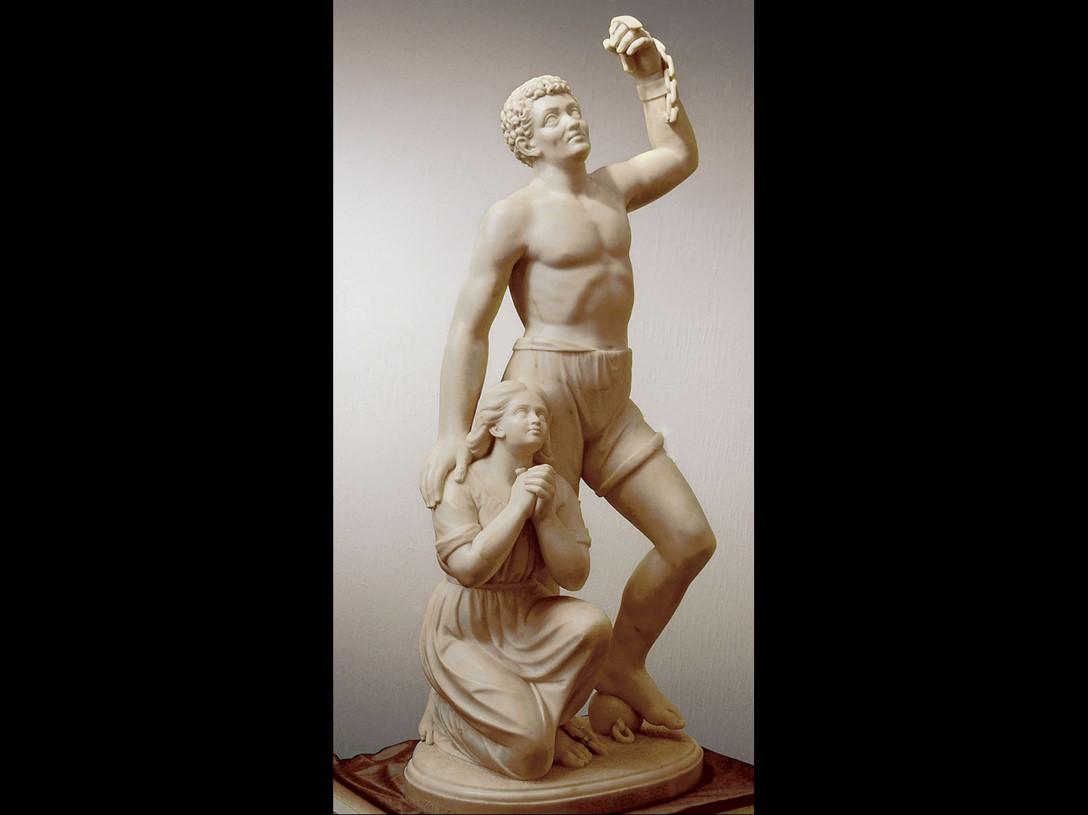

Such work, which continued through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, all suggest the sculptural back doors through which eighteenth-century women artists entered the domain of public sculpture. In wasn’t until the mid-1800s that a new generation of women stone sculptors emerged. Going against the accepted role of wife and mother, these women were often ridiculed and ostracized. The lucky ones had the financial and emotional support of their families and the private means to afford materials and formalized training. In America, women could attend academies such as the National Academy of Design and the Art Students League in New York, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, and the Art Institute of Chicago. However, many chose to study in Italy and established studios there, taking advantage of the company of stone carvers and craftsmen as well as the ready supply of white statuary marble. These artists worked in the prevailing neoclassical style for their monuments and commissions. The first “school” of women sculptors arose around Rome based Harriet Hosmer (1830-1908,) Anne Whitney (1821-1915) and Edmonia Lewis (1844-1911.)

Six of the many women who broke through the gender ceiling

Harriet Hosmer (1830-1908)

Harriet Hosmer (1830-1908)

began her life in Watertown, Massachusetts and from an early age was often to be found in a clay pit near her home “modeling horses, dogs, sheep, men and women.” Her high spirits and strong will earned her expulsion from school not just once but three times. After school she decided to pursue sculpture in earnest. Although her father encouraged her, the rest of Massachusetts was not so understanding. Even her friend Nathaniel Hawthorne despaired over her unmarried state and her “jaunty costume” which consisted of a “sort of man’s sack of purple broadcloth, a male shirt, collar and cravat and a little cap of black velvet.” Fortunately, she came from a supportive family who enabled her to go to Rome and study. Even though her “Beatrice Cenci” (1857), was a triumph at the 1857 Royal Academy exhibition in London, she nevertheless still had to deal continually with rumours that one or another of her male associates did her work. Slander and prejudice dogged most of her career. Anne Whitney (1821-1915), also from Massachusetts, was driven by a passion for social justice and many of her sculptures reflected her social sympathies. Her colossal “Africa” (1864, destroyed) embodied antislavery sentiments in an idealized neoclassical form. Sometimes her work proved too controversial—for example, Roma (1869), a realistic depiction of the city of Rome as an impoverished old beggar woman, which with its irreverence caused a sensation when it was exhibited. Experiencing much of the same prejudice that Harriet Hosmer faced, and with a similarly supportive family, Anne too went to Rome where she was one of several young American women sculptors who went to work there among their male colleagues. In 1875 Whitney won a national commission to portray abolitionist Charles Sumner, but, when it was discovered that the designs were by a woman, her submission was rejected.

Edmonia Lewis (1844-1911)

Edmonia Lewis (1844-1911)

had not only to struggle with prejudice against women sculptors, but also against her mixed black and Chippewa heritage. After school she went to Boston, the center of liberal thought at that time, and began studying with Anne Whitney. Eventually, she too went to Rome to study, there creating life-size marble works celebrating emancipation and her Indian heritage. Although some feel that her work lacks the conventional polish of some of her contemporaries, her passion, expressiveness and ethnic content have great appeal. Her life-size marble “Forever Free” powerfully symbolizes the emancipation of black people. Lewis said that she was expressing her “strong sympathy for all women who have struggled and suffered.” Refusing to be stopped by racism or the patronizing attitudes of her times, she became the first major black sculptor in America.

Anna Hyatt Huntington (1876-1973)

Anna Hyatt Huntington (1876-1973)

In the early 1900s, although it was still considered odd for a woman to choose sculpture as a vocation, more and more women became accepted. One of the most respected and influential, was the renowned sculptor of animals, Anna Hyatt Huntington, who broke new ground for women sculptors. Her bronze “Joan of Arc” (1915) was the first equestrian statue by a woman. Independent of spirit, her formal training was short and she could often be found at the Bronx Zoo, “a tall young woman in a tailor-made frock and red plumed hat, doing a clay study of a bison.” She did not attend art school aside from studying briefly at the Art Students League in New York City. Huntington was a self-made success with a natural talent for modeling detailed sculptures of animals and enormous equestrian sculptures portraying the likes of Joan of Arc (New York City), El Cid (New York City and Seville, Spain), and Andrew Jackson (Lancaster, South Carolina.)

Although she had no plans to marry, she finally accepted the repeated proposals of wealthy philanthropist Archer Huntington. Now, with unlimited financial resources at her disposal, she was able to work on a larger scale and support the work of other artists. The Huntingtons were responsible for the founding of fourteen museums and four wild life preserves. The most famous of these being the 9,000 acre Brookgreen Gardens in South Carolina founded by Anna and Archer in 1931. Originally intended as a setting for her sculptures, she soon commissioned works from her friends and it eventually developed into this country’s first public sculpture garden and has the world’s largest collection of figurative sculpture by American artists in an outdoor setting. This award-winning sculptor lived to be nearly 100, making art until the year before she died.

Vinnie Ream (1847–1914) Ream is the sculptor of an iconic marble Abraham Lincoln that stands in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol (unveiled 1871.) A virtually untrained 18-year-old, Ream was the first woman to win such a commission from the federal government. She completed a plaster model for the statue in her studio and then, accompanied by her parents, took it to Rome in 1869 to translate it into white Carrera marble. In 1875, up against better-known male sculptors, Ream again won a major commission from the U.S. government, this time for a bronze of Civil War hero Admiral David G. Farragut. She went on to create portrait busts of other military and political figures of that era. Two later sculptures—Samuel Kirkwood (1906) and Sequoyah (1912-14)—are displayed in the U.S. Capitol’s National Statuary Hall. Ream abandoned sculpture for many years in deference to her husband’s wishes, but in her later years she executed a statue of Iowa governor Samuel Kirkwood (1906), as well as the model for a statue of Sequoyah (1912–14), both for Statuary Hall in the Capitol.

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney 1875-1942

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney 1875-1942

Bearing the surnames of two notable families, Gertrude could certainly have gotten by as a socialite, but she became a highly influential art patron (cofounding the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1930) and pursued sculpture, finding that she had a natural talent for it. Whitney created numerous dramatic memorials throughout the country and the world. Some of her better-known works include The Titanic Memorial (1914–31; in Washington, D.C.), The Scout (1923–24; in Cody, Wyoming), and the Peter Stuyvesant Monument (1936–39; in New York City).

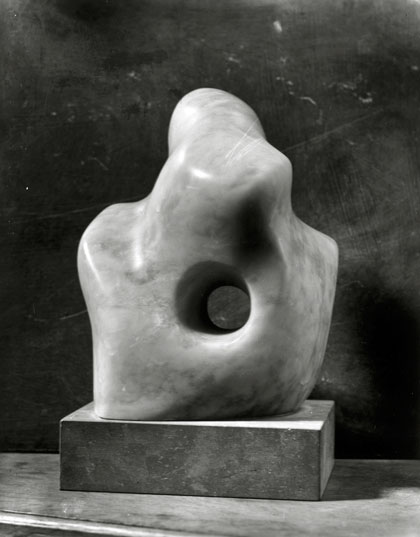

But ironically, the prevalence of stone sculpture by women during the Suffrage Movement of the latter part of the19th Century and the early 1900s began to take a downturn in post-war America. Around the 40s, the image of woman as homemaker seemed to take over and it wasn’t until the feminist movement of the 1970s that acceptance of women in new fields began to be seen again. Little by little, prejudice against women as sculptors grew less adamant and by the late 20th century there were many successful women stone sculptors. Cleo Hartwig (1911-1988), Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975,) Jane B. Armstrong (1921-2012) and Anna Mahler (1904-1988,) to name only a few. It has been a long slow ascent for women as sculptors. Starting in caves making household crafts and goddess worship paraphernalia, they were denied anything much more than that until a few began modeling figures in wax to make a living with traveling displays. With a few lucky breaks and access to some money, a handful of women began producing world-class art, allowing them to finally force their way into what had been man’s domain and produce their own renaissance.

Here’s to women everywhere, past and present, who have worked hard to follow their muses and create their magnificent art that we see throughout the world today.

Very early on a Saturday back in June, 2017, we loaded my pick-up with a generator and lots of supplies and headed to the Ravensdale gravel quarry to make this successful boulder split.

Very early on a Saturday back in June, 2017, we loaded my pick-up with a generator and lots of supplies and headed to the Ravensdale gravel quarry to make this successful boulder split.

“We don’t make mistakes, we just make happy accidents.” -

“We don’t make mistakes, we just make happy accidents.” -

From early grade school, I was interested in art. Although I spent a good part of my early life on the high seas with the US Navy, I always took the opportunity to view art in Asian and European cities and while on shore duty stations, I attended life drawing and painting classes offered at local colleges. My most enjoyable learning experience in life drawing and oil painting took place at the

From early grade school, I was interested in art. Although I spent a good part of my early life on the high seas with the US Navy, I always took the opportunity to view art in Asian and European cities and while on shore duty stations, I attended life drawing and painting classes offered at local colleges. My most enjoyable learning experience in life drawing and oil painting took place at the  The clay portraiture process taught me how hard it is to get a likeness and to keep it once found. It also helped me to better understand the construction of the cranium, allowing me to create a very credible portrait of someone that I have never met.

The clay portraiture process taught me how hard it is to get a likeness and to keep it once found. It also helped me to better understand the construction of the cranium, allowing me to create a very credible portrait of someone that I have never met.  The Rococo period in marble portrait sculpture can hardly be better illustrated than by the Italian Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s portrait bust of Francis I D’Este, Duke of Modena, which was completed at the midpoint of the 17th century. This super realistic piece surrounds a face, that looks to be alive, by fantastically long cascades of curled hair, dream-like billowings of fabric in a swirl around his armored torso, with soft touches of crocheted lace at his neck.

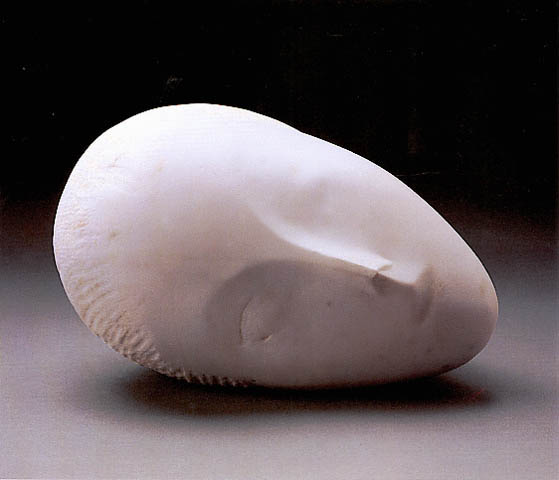

The Rococo period in marble portrait sculpture can hardly be better illustrated than by the Italian Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s portrait bust of Francis I D’Este, Duke of Modena, which was completed at the midpoint of the 17th century. This super realistic piece surrounds a face, that looks to be alive, by fantastically long cascades of curled hair, dream-like billowings of fabric in a swirl around his armored torso, with soft touches of crocheted lace at his neck. Gone are all the marvelous coverings of cloth and metal. Even the hair is reduced to a mere indication of a few strands on the top of the head. Brancusi’s head isn’t even placed upright on a pedestal, but simply lies like

Gone are all the marvelous coverings of cloth and metal. Even the hair is reduced to a mere indication of a few strands on the top of the head. Brancusi’s head isn’t even placed upright on a pedestal, but simply lies like

Hepworth was a very prolific sculptor, and produced over six hundred works of art over her lifetime, including many works of public art in England and across Europe. Most notable was "SINGLE FORM" installed in the courtyard of the United Nations in New York on June

Hepworth was a very prolific sculptor, and produced over six hundred works of art over her lifetime, including many works of public art in England and across Europe. Most notable was "SINGLE FORM" installed in the courtyard of the United Nations in New York on June

Harriet Hosmer (1830-1908)

Harriet Hosmer (1830-1908)  Edmonia Lewis (1844-1911)

Edmonia Lewis (1844-1911)  Anna Hyatt Huntington (1876-1973)

Anna Hyatt Huntington (1876-1973)

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney 1875-1942

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney 1875-1942

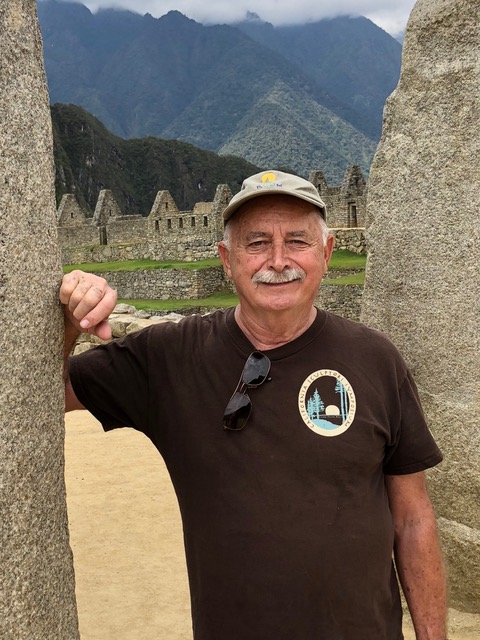

Thanksgiving was spent with Alfonso Rodriquez Medina and his three loving sons, at their home and marble factory in Lima. Visiting him in his homeland was unforgettable. If you don’t know Alfonso, he attended Camp B several times. This master craftsman danced while he forged tools. He sang as he carved stone as gifts to the auction.

Thanksgiving was spent with Alfonso Rodriquez Medina and his three loving sons, at their home and marble factory in Lima. Visiting him in his homeland was unforgettable. If you don’t know Alfonso, he attended Camp B several times. This master craftsman danced while he forged tools. He sang as he carved stone as gifts to the auction.

The stone edifices of hundreds of years ago brought up many questions. How were these multi-ton boulders of granite, andesite

The stone edifices of hundreds of years ago brought up many questions. How were these multi-ton boulders of granite, andesite  In closing, I strongly suggest going to Peru. Consult your MD about Rx for high altitude sickness prevention, and enjoy the coca leaves and tea!

In closing, I strongly suggest going to Peru. Consult your MD about Rx for high altitude sickness prevention, and enjoy the coca leaves and tea!

CROSSING POINT is the name Kalia Gentiluomo gave to her original project after a, now gone, pioneer swing bridge over the channel. In its final

CROSSING POINT is the name Kalia Gentiluomo gave to her original project after a, now gone, pioneer swing bridge over the channel. In its final

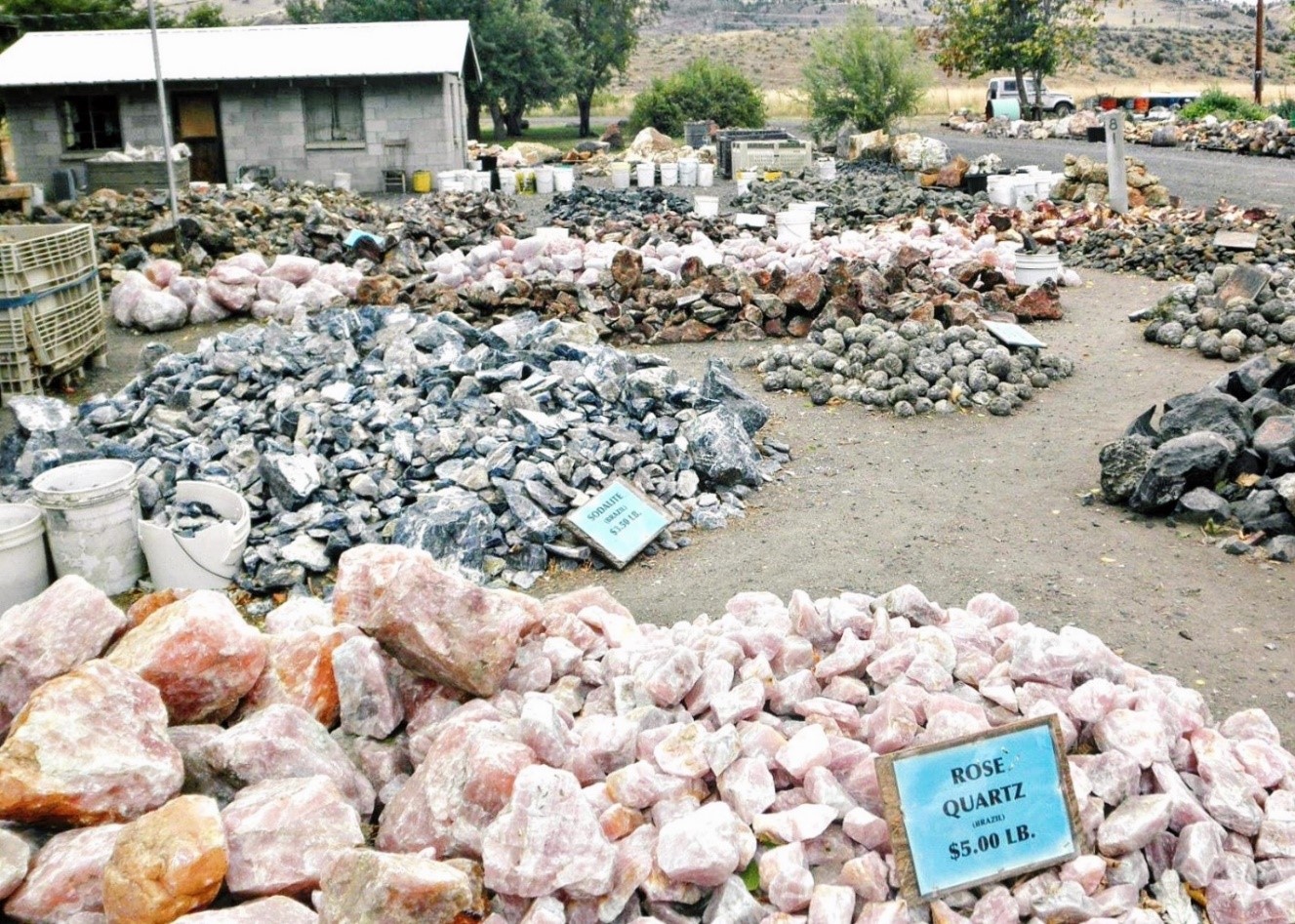

The Richardson Rock Ranch

The Richardson Rock Ranch

And what about digging for my own special treasure of thundereggs in the red, dusty,

And what about digging for my own special treasure of thundereggs in the red, dusty,

Background – After interviewing and being awarded the job at the end of 2015, I went to work researching the island and the school and developing concepts. The selection committee chose a concept centered on the metaphor of drawing out or

Background – After interviewing and being awarded the job at the end of 2015, I went to work researching the island and the school and developing concepts. The selection committee chose a concept centered on the metaphor of drawing out or

We all learned some things to consider the next time around - take account of surface weathering, consider carefully how both the mass and the form of the stone will constrain (or not!) the splitting plane, take plenty of time between rounds of hammering…. We might have intentionally taken off a corner at the start, to get a more oblong shape, and to tell us more about the grain direction of the stone. I’d say our first split line was running somewhat perpendicular to the bedding plane. It’s worth noting that the grain direction of the boulder became much more obvious to me recently when I began doing some final pointing by hand on one of the split faces. As with wood, hand tools tell you things about a stone that power tools simply don’t!

We all learned some things to consider the next time around - take account of surface weathering, consider carefully how both the mass and the form of the stone will constrain (or not!) the splitting plane, take plenty of time between rounds of hammering…. We might have intentionally taken off a corner at the start, to get a more oblong shape, and to tell us more about the grain direction of the stone. I’d say our first split line was running somewhat perpendicular to the bedding plane. It’s worth noting that the grain direction of the boulder became much more obvious to me recently when I began doing some final pointing by hand on one of the split faces. As with wood, hand tools tell you things about a stone that power tools simply don’t!

March 15, 2017 - Today as I worked, I drifted into concerned speculation as to what might be the gender of this frog. At first, I concluded it was surely male because although it’s ultimate home will be Arlington, ‘way down there in Washington State, it stubbornly exhibits a stony reticence in asking for directions how to get there. It’s been said that’s a male thing— though mainly by my wife, mind you. But now I’m not so sure. Here’s why: You see, each spring I’m overtaken by an annual hankering to head out salmon fishing. Invariably, this yearning occurs just as the early grass needs cutting and our property begs for

March 15, 2017 - Today as I worked, I drifted into concerned speculation as to what might be the gender of this frog. At first, I concluded it was surely male because although it’s ultimate home will be Arlington, ‘way down there in Washington State, it stubbornly exhibits a stony reticence in asking for directions how to get there. It’s been said that’s a male thing— though mainly by my wife, mind you. But now I’m not so sure. Here’s why: You see, each spring I’m overtaken by an annual hankering to head out salmon fishing. Invariably, this yearning occurs just as the early grass needs cutting and our property begs for

I knew the time was close, for I have been intimately connected to this frog for months; and you can’t be that close and not sense the stirrings within. When I absolutely knew, on this auspicious morning, that the frog’s time had come, I prepared very carefully. Oh, I wasn’t expecting a frenzied wiggling to begin, or peeing all over the place like an excited puppy. No. I knew it would be a more dignified moment than that. I made careful preparations. I shed my mask and glasses and tossed off my tattered gloves, revealing the earth-person underneath for the momentous occasion I knew was upon us. I stood resolutely in front of the frog, looking straight into its freshly carved eyes. It looked back in typical stony silence, its countenance one of stoic expectancy. I had carefully rehearsed my lines to make this magic moment happen.

I knew the time was close, for I have been intimately connected to this frog for months; and you can’t be that close and not sense the stirrings within. When I absolutely knew, on this auspicious morning, that the frog’s time had come, I prepared very carefully. Oh, I wasn’t expecting a frenzied wiggling to begin, or peeing all over the place like an excited puppy. No. I knew it would be a more dignified moment than that. I made careful preparations. I shed my mask and glasses and tossed off my tattered gloves, revealing the earth-person underneath for the momentous occasion I knew was upon us. I stood resolutely in front of the frog, looking straight into its freshly carved eyes. It looked back in typical stony silence, its countenance one of stoic expectancy. I had carefully rehearsed my lines to make this magic moment happen.

We often hear it

We often hear it

Welcome to the podcast!

Welcome to the podcast!

With basalt the learning curve is steep. How much detail is realistically achievable? Curves need to be polishable. Small projections aren’t a good idea. And then there was always that pushy muse in the background repeating, “Nothing ventured, nothing gained.”

With basalt the learning curve is steep. How much detail is realistically achievable? Curves need to be polishable. Small projections aren’t a good idea. And then there was always that pushy muse in the background repeating, “Nothing ventured, nothing gained.” As I waited for the ferry back to Lopez Island on my way home that year, filled with wild excess energy from seven days with seventy other stoned fanatics gathered on “Planet Granite,” I noticed the black long necked cormorants drying themselves on the dock pilings. Wet, black, shiny and plastic! There had to be a way to find one in that other basalt column in the back of my truck that didn’t have a foot long neck and a narrow beak waiting to be snapped off by an unplanned encounter with a vacuum cleaner. Like otters, they are amazing contortionists and before long one showoff twisted his neck around to preen the back of his wing and I was a witness. The deal was sealed and the rest history …. and chips and dust and pools of water.

As I waited for the ferry back to Lopez Island on my way home that year, filled with wild excess energy from seven days with seventy other stoned fanatics gathered on “Planet Granite,” I noticed the black long necked cormorants drying themselves on the dock pilings. Wet, black, shiny and plastic! There had to be a way to find one in that other basalt column in the back of my truck that didn’t have a foot long neck and a narrow beak waiting to be snapped off by an unplanned encounter with a vacuum cleaner. Like otters, they are amazing contortionists and before long one showoff twisted his neck around to preen the back of his wing and I was a witness. The deal was sealed and the rest history …. and chips and dust and pools of water.

2015 found me wading in the river. I finally pushed off the foundation, relinquished the apartment and went peripatetic. Homeless. The day I found out that was to happen, the day after returning to my studio from Camp B, Rubble was cast as the foundation broke off entirely. A fit of ink projected the lighthouse onto a studio wall.

2015 found me wading in the river. I finally pushed off the foundation, relinquished the apartment and went peripatetic. Homeless. The day I found out that was to happen, the day after returning to my studio from Camp B, Rubble was cast as the foundation broke off entirely. A fit of ink projected the lighthouse onto a studio wall. I wanted to have the base before returning to Vashon, so I detoured for a few days to visit a friend on another island with a studio surrounded in forest. I took the lighthouse out into this eighth workspace to cut and laminate a solid base of old, repurposed mahogany. By now I was savoring the last drops of my homesickness. I still had no plan and no specific place to lay my head, but that didn't matter so much. One foot, a few toes, were still in the river, and the rest of me had pulled up onto a new land.

I wanted to have the base before returning to Vashon, so I detoured for a few days to visit a friend on another island with a studio surrounded in forest. I took the lighthouse out into this eighth workspace to cut and laminate a solid base of old, repurposed mahogany. By now I was savoring the last drops of my homesickness. I still had no plan and no specific place to lay my head, but that didn't matter so much. One foot, a few toes, were still in the river, and the rest of me had pulled up onto a new land.

For an in depth critique of the show, go to

For an in depth critique of the show, go to