Stories in Stone - Mar/Apr 2004

- Details

- Created: Tuesday, 02 March 2004 03:27

Ed: This article is reprinted here with permission and originally appeared in Pacific Northwest, The Seattle Times Magazine, January 24, 1999. Sculpture NorthWest will continue this article in the May/June Issue.

Every time you walk through downtown Seattle, you are traveling along a geologic time line. A lengthy stroll could take you from the 1.6-billion-year-old Finnish granite of 1000 2nd Avenue past the Seattle Art Museum and its relatively young, 300 million year old limestone walls. A couple of blocks later you could hunt for fossils, some up to four inches wide, embedded in grey limestone at the former Gap store on 4th Avenue. Around the corner and underground in the Westlake Mall bus tunnel, you could end your walk near the burnt oatmeal-colored travertine deposited less than two million years ago near the Rio Grande River in New Mexico.

Seattle’s use of stone, as opposed to wood, for building began soon after June 6, 1889, the day of Seattle’s great fire, which consumed most of the downtown business district. Like most cities, Seattle started with local rock, using material quarried near Tacoma, Index, and Bellingham. Stone spread through the city into street paving, curbs, walls, and foundations. As the city grew and became more wealthy, builders sought out stone from Vermont and Indiana. And finally, with better transport systems and cutting technology, local or regional geology became obsolete as contractors obtained rock from South Africa, Brazil, and Sardinia.

Studying the geology of various kinds of building stone, offers an intriguing introduction to the natural and cultural world of Seattle. For the intrepid wanderer, the story is easy to read because it is written on walls all over town.

Salem Limestone

Limestone has been a popular building material for several thousand years. For example, an observant visitor to the Sphinx would find 50-million-year-old oysters and corals scattered throughout the great beast’s limestone body.

The most popular building stone in the United States, known to geologists as Salem Limestone, comes from quarries near Bedford, Indiana. This white-to-buff rock has been used in the Empire State Building, San Francisco City Hall, and the Pentagon. In Seattle it graces the exteriors of the Seattle Art Museum and the Seattle Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. What makes this stone interesting is not its popularity, but its fossils, for Salem consists of layer upon layer of minute organisms.

Deposition of this limestone occurred 300 to 330 million years ago in a shallow, clear, tropical sea. The warm waters supported a diverse range of swimming, crawling, and bottom-dwelling invertebrates. When they died their bodies collected in a watery cemetery on the sea floor, eventually solidifying into a 40-to-100-foot-thick stone menagerie. This matrix of corpses formed a limestone that cuts cleanly and evenly in all directions.

Crinoid stems, small poker-chip shaped discs, are the most common recognizable fossil. Crinoids were small invertebrates related to starfish and sand dollars. They resembled plants with a root-like base, a flexible stem, and a flower-like top. Another common fossil is from a colonial animal known as a bryozoan. These sedentary creatures formed communities that resembled a pile of Rice Chex cereal. Only bits and pieces of their fragile homes remain. Wave action from long ago tides destroyed most of the shells from other animals that plied the sea, but careful investigation reveals a smattering of half-inch-long snails, oysters, and clams.

Finnish Granite

In recent years economists have started to bandy about the term “global economy.” Politicians hold conferences to promote trade between North and South America or across the Atlantic Ocean. The global economy is old hat for those in the building trade. Two thousand years ago, African marble was being shipped to Rome. At the turn of the last millennium, William the Conqueror built castles in England from French stone, which his marauders carried across the channel. Modern contractors have expanded this practice and opened up a world-wide market for stone trading. Finnish rock is a good example.

Despite its location almost half-way around the globe, Finland provides many different building stones to the Seattle area. Reddish, pink, and brown granites are used in the U. S. Bank Centre, Key Tower, Westlake Mall Metro bus tunnel, and Century Square. All of these rocks formed more than 1.6 billion years ago.

From a geologist’s point of view, the most interesting parts of the Finnish rocks are the large minerals. Several varieties of feldspar, the most common mineral on the Earth’s surface, dominate the different Finnish granites. The large crystals, some up to three inches long, indicate that the rock cooled slowly, deep underground. When magma reaches the surface and becomes lava, as in a volcano, then it cools too quickly for good crystal formation.

Surprisingly, the Finnish building stones were not shipped directly to Seattle. Instead, the granite’s journey began with a stop in Italy, home of many of the world’s premier stone cutting companies. Contractors often transport rocks to Italy because of lower costs and higher quality stone products. As economists are learning, the global economy is more complicated than it looks.

Italian Travertine

Like Rome, Seattle was built on seven hills. Like Rome, many Seattle buildings incorporate a type of limestone known as travertine into their structure. Coincidentally, much of the travertine used in Seattle came from quarries located near Rome, where the 30-million-year old rock has been used for over 2000 years. The best known example is the Colosseum with its massive travertine blocks.

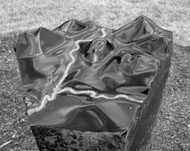

Unlike the two other types of limestone discussed in this article, travertine does not form in the sea. Instead, it precipitates from calcite-rich water associated with springs or caves. A good modern example is Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park. As water spilling out of a spring evaporates, any solids carried in solution settle to the ground, like the settling of spices in Italian salad dressing. In travertine, calcite is the primary solid, building up layer upon layer as the spring continues to expel water. The holes found in travertine indicate deposition around plants. Millimeter-wide calcite crystals fill many of the holes.

Builders use travertine indoors and outdoors in Seattle. In some structures, like the old Nordstrom building, contractors filled the holes in the rock. This is for preventative maintenance. In a colder location, like Boston, water seeps into the cracks, freezes, expands and breaks the rock. On one Boston building every panel had to be reattached with external bolts. Seattle’s moderate winter climate, however, has little effect on the holey, dirty white rock. Good examples are the Washington Federal Savings building, the interior bank area of the Rainier Tower, and the Pacific Building.