Artist Spotlight - Joyce Taylor

This is an interview with sculptor Joyce Taylor of Shelter Bay, La Conner. She is a regular at the yearly NWSSA summer symposium at Camp Brotherhood. She's been a member for eight years and is an unassuming 'jewel" among us. At 70 (and getting younger), she has created an array of beautiful work in many styles and media over a period of some 2S years. She is always interested in improvlng and challenging her skills. I suggest seeking her out for feedback on your work, as I have on many occasions.

We start by looking at her work around her home: "Introspection", a large and gorgeous piece in Carrara marble, which she roughed out while working at a studio in Italy. Then, "Moods of the Sea", a waveform in alabaster, and "Leroy", a head in dark terra-cotta with dark patina.

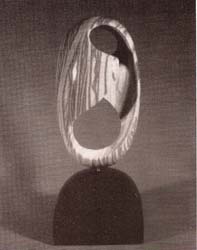

"Quiet Opposition" is a beautiful, non-representational form describing two people having a slight disagreement, hand-tooled in alabaster. She integrated the base block with the stone, leaving a lumpy organic texture, done by wire brushing the alabaster until smooth and soft looking. We look at her large "Frog" in translucent alabaster, seemingly ready to hop, also carved with an integrated base. We look at her life-like fox head, "Red Fox", in bronze with red patina.

JT: I did that in Scottsdale with an AnimaIier. He showed up one day and said, "In four hours I want a skull done." We did the skull in the mODling and started putting on the muscles in the afternoon; I learned a lot by this "building up" process.

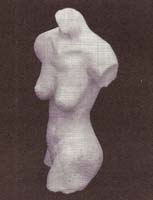

With "Torso" in alabaster, polishing that bottom was the most sensuous thing in the world. It's always difficult when doing a torso to know how to end up in the shoulders and arms. It's so hard not to have it be static. You've got to have some movement in it.

SS: In forms like this (abstracted torso form) do you have a sense of trying to express something in particular?

JT: It just happens. Usually before I start a piece of stone, I set it out somewhere for two or three weeks. Every so often I turn it and look at it. Then some morning I say "Hmmm" and off! go, carving the stone. It's just there and you begin to get a rapport with it; it's sort of neat.

SS: How long have you been carving and creating?

JT: Twenty-five years.

SS: How did you get started?

JT: I had to have a wrist operation, so I quit work as an economist and securities analyst. While I was recovering I went to a community college class called "You Can Draw", taught by a little old lady. No matter what anyone did it was "marvelous". She was an enormously positive person and made everyone want to do more. I had a grand time.

One day I sat down and did a portrait of John Wayne. I don't know why, as I don't even like John Wayne. When my husband came home he took a look and said "Oh my God" (positively impressed). So, at Christmas he gave me a year at the Laguna School of Art. I never had any art training before that and Ijust took off. I tried watercolors, printmaking, terra-cotta sculpture, and lots of life drawing. [' m a strong advocate of life drawing and sculpture at the same time. Nothing teaches your eye to see like life drawing.

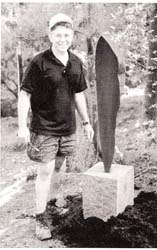

My terra-cotta class instructor handed me a piece of stone, a chisel and a hammer, and said "Make something." (Joyce brings out a "primitive" carving of a salmon). That was my first stone piece.

This is the only piece I've ever done that I have had to explain. "Flight of Childhood" is a child form held by a parent's hand while the child is trying to spread his wings. (It has a very mystical quality to it.)

(We look at her indoor carving area, a 12' x 12' room incorporated into the garage. A Foredom flex shaft grinder hangs next to an alabaster waveform in progress.)

JT: Ever so often I have to do a piece of stone by hand. You have so much more rapport with the stone when you do. Otherwise I use power tools. (We look at "Crow" in fossiliferous limestone). We did not enjoy working together. The stone was hard to carve and dirty.

She direct carves her large waveforms in alabaster.) "This is the fifth one I've done, and let me tell you, they sell." She mounts the colorful alabaster sculpture on a polished black Belgian marble base. We look at other works in progress around the studio: "Leroy", a torso fonn in terra-cotta with applied patina. We look at a 24" high clay figure to be cast in bronze. We look at her clay maquette for a large bear, which is now being roughed out in marble.

JT: Unfortunately, the piece of Carrara marble for the bear is so valuable that he's sat for three years with his head just a block. The stone is from the same vein that Michelangelo used for "David". And now that vein is quanied out.

(We talk about her trip to Pietrasanta, Italy, where she studied and worked for two months at the Silverio Paoli studio.)

JT: It was absolutely grand. You went through these old wood doors into a 30' high studio, then into a courtyard with an overhead grape arbor. You look up the hill to the old battlements. I elected to work outside under the grape arbor, which was delightful. We worked until 1100n, then bought lunch in the local market, then worked until fi ve. It was HOT! We'd shower and go out for wine, bumping into people from all over: Russia, Japan. Dinner (multi-course meal at the pension) was at 9 pm, so at I pm you had to go for a walk. Then it was back to the studio at 7:30 the next morning. Silverio, master of the studio, was a grand person. He would take us around, get us stone, and show us various outstanding sculptors' studios. His son, a master at finishing, would teach liS finishing techniques while Silverio translated. Tools were abundant and my fecding frenzy got expensive.

(We continue the tour to an enclosed side yard).

JT: This is my outside worktable with my compressor nearby in a sound shield enclosure. r have three pneumatic handpieces, but really like the smallest, a Y2" Cuturi, the best. You can cut the air back on that one and go anyplace. (We look at a fine collection of carbide-tipped chisels for her air-powered handpieces.)

(We look at her photos).

JT: You have to be so careful of what you say when someone wants to buy something. I couldn't use a person's name as a sculpture title for pieces in the Laguna Beach Gallery. The owner felt that someone might love the sculpture, but might have a bad association with the name. This bronze figure, called "Apprehension", was too strong to live with. A couple saw a photo of it and tlew over from Idaho

to buy it. She thought it was "the sweetest thing", where I saw it as an ominous and threatening figure. I had to keep my mouth shut.

SS: You seem so fluent in realistic, abstract, and nonrepresentational styles. For example, "Torso", an abstracted torso form, seems both realistic and abstracted, as if it could be seen both ways. Is that a conscious choice on your part?

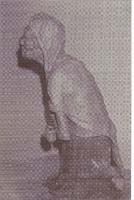

JT: I put a twist or turn in everything I do, absolutely unconsciously. It just happens. (Looking at another photo). This is a large clay figure called "Pathos", an emaciated figure in a tattered shawl. This is the first of a series representing the emotions.

SS: Do you find you prefer modeling clay or carving?

JT: I like them all. That's the problem with art, there's so much you could do, but you can't do it all.

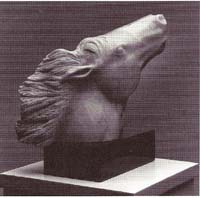

SS: With "Wild Horse", did you model or draw before you carved? You get such a good sense of movement.

JT: I walked near a pasture where a horse was kept. I fed him lots of carrots and I'd feel his nose, and his bones.

SS: How much do you work through galleries?

JT: I sold through a gallery in Laguna Beach for years. The gallery owner and I had excellent rapport, important for a continuing relationship. We liked each other. I ended up selling from my home studio when we moved to Gig Harbor.

(Now living in La Conner, WA, she is showing at the Galen Gallery in Mt Vernon, WA, and, in her home.)

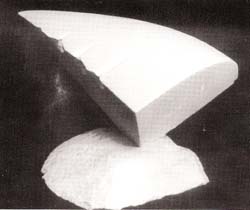

SS: (We look at a piece called "Discovery", a non-representational form with plane and concave elements, in gray-white Carrara marble.) Were you inspired by the stone's original shape?

JT: No, the previous piece was very demanding and I wanted to have some fun with this one. I didn't know where I was going with it so I cut a plane here, a plane there, then I thought "How am I going to relate these?" You've been there. I had fun with it.

(We look at a photo of "Seal", coming out of the water.)

JT: It was in a show in Tacoma. I was delighted because it was purchased by a Seattle architect for his entrance lobby. It's quite a large piece and I was thrilled that an architect bought it. It's interesting that over one-third of my work has gone to corporations or professional offices. The first piece I ever sold went to the 3M Corporation.

SS: Were you creating art when you were working in the securities business?

JT: No, I didn't know that I could draw. When I was young I drew a child's stick figures of the family, and my mother said, "You haven't much talent, have you?" I thought no, I guess 1 don't. I never did another thing until I took up art in my forties. I guess it was meant to be.

SS: It sounds as if you just woke up one day and started work.

JT: I explored different art mediums, but the stone bug bit. When the stone bug bites, you stay bitten. Stone's challenge is enduring.

(We look at "Jonah and the Whale", a terra-cotta form created by an instructor's assignment to combine human and animal forms.)

SS: Do you ever teach sculpture? I think you'd be a great instructor with such diverse talent.

JT: In the summer, sculptor friends worked with me at my studio. I thoroughly enjoy helping people with the relationship with their stone. But I get frustrated when I find that people are sometimes reluctant to really get into the stone. They seem to want to put the eyes in right away in an animal, or human face. I like to say "Come on, let's get the form first, shut your eyes and see into a mist and look at the form, forget the detail for a while." It's hard to get people to do that.

SS: I know you're involved and interested in many art forms, but are you primarily a sculptor?

JT: Yes. As a sculptor you have to become very observant. One of the most interesting things we did at the summer symposium was when Rlch Hestekind had us pair up and walk into the woods to observe what we were drawn to in a natural setting. A twig and leaf on the water - you have to let yourself see. (Since then she's noticed how unobservant people can be). Observe the world, it's just marvelous!

When I started carving I had a free source of stone, so I never had any fear of the cost. As a result I pushed stone to its limits and thought "so what" if things went badly. Well, I pay for stone now but I've learned not to be afraid of it. I thoroughly enjoy stone carving and I will do it as long as I enjoy it. When I was showing in Laguna Beaeh I was a resident artist and I worked full time at it and I liked it very much. I feel I had more growth then than now. You don't grow unless you challenge yourself.

She talks about her next creative challenge being portraiture in stone and and notes some fear about "getting it right". Her advice for other artists: "Enter juried shows. But don't do it until you find out who the jurors are."

She recounts being rejected for a show because "stone sculpture is passe, it needs to be incorporated with ntixed media", according to this juror.

JT: It's your job to find out about the jurors and their background. You're wasting your time if you don't. They may be into completely abstract art, or may be completely into realism.

I was fortunate when I started because I entered a juried show. I won Best of Sculpture and Best of Show. I got a call from a Laguna Beach gallery owner who said that a show juror had told her about my work and that she would accept my work sight unseen. I was in that gallery for years (Esther Wells Collection); your recognition from juried shows, if you pick the right ones, is highly valuable. It leads to contacts and phone calls.

Joyce's parting thoughts: "ENJOY!" Which she is obviously doing, big time. And we'd be glad to join her.

Thanks Joyce!