The following is both an interview with Vic Picou and a call for a new "Director of Symposia". Over the years since the group's first "gathering" in 1987, Vic has emerged as an invaluable contributor to the growth, development and maintenance of NWSSA and its four yearly symposia. He has been at the literal center of the group, being a past President of the Board for several years and running its office from his home. He's the one who answered those phone calls at all hours. At the same time he has directed and helped develop the symposia we currently offer.

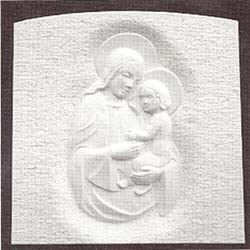

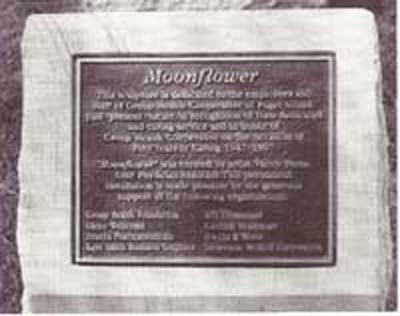

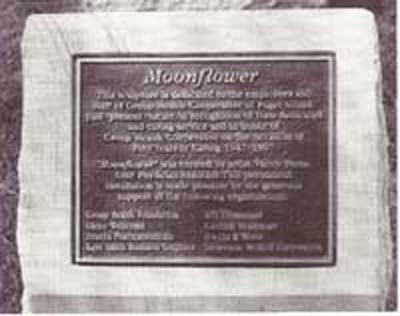

All of this was done in the midst of a professional life as a Physician Assistant, and an active sculptor. Vic shows and sells his work regularly, has produced a major monumental work ("Moonflower" installed at Group Health Capitol Hill Seattle) and is an avid creator. He is currently completing a sculpture of St. Thomas for a church in L.A. (to be installed in a niche 60' up).

To me Vic epitomizes the spirit of this group. He is a collaborative, invitational, "people" person with a big heart who has given in uncountable ways to the life of this group, while doing his own art. He personally portrays the positive values of the group and has been instrumental in establishing them by example. He seems to always be encouraging others in their art and has a wellspring of enthusiasm. For all that, I want to offer appreciation and thanks.

Vic will be moving to California in about two years. He needs to reduce his NWSSA responsibilities by about 50%. This means he will "only" be able to manage the CB symposium and we need a committed person to be our new Director of Symposia (DOS). This person will work with symposia managers and support them as they develop and run the individual events. These include Whidbey Island Workshop, WA (3 day hand carving retreat), Silver Falls Symposium, OR (5 days), Camp Brotherhood Symposium, WA 00 days), and Camp Columbia Symposium, Thetis Island, B.C., Canada (5 days). (I encourage all to read/re-read the July/August NWSSA newsletter for multiple perspectives on the qualities of these symposiums.)

Vic and I start to talk about his work as DOS:

VP: I've got a responsibility to the Board of Directors, and to the membership. In actualizing that responsibility there are many activities. We developed a set of "symposium guidelines" (eight members met for hours, five years ago). It's my responsibility to make sure those guidelines are followed. Each fall, the separate symposium committees begin to look at how they'll do their program for the following year. They evaluate the last event, decide on faculty, and establish an approximate budget for the next year. I put all the separate budgets together and present this to the Board at the first of the year.

SS: How do you relate to the managers of each symposium?

VP: For example, a year ago, Mark Andrew agreed to direct the Silver Falls Symposium, and I approved that. I drove to the site with Mark and laid out the job description to him and set the tone for the development of his committee. Then he took over from there, using the guidelines (an explanation of the basic structure and requirements) to develop and work with his local committee.

After that, it was a matter of staying in contact frequently, to check how it was going, asking who do you have to help you?, what can I do to help you?, be snre to snbmit your budget by deadline, and so on. So it's monitoring and supporting on a month-to-month basis. Helping him with the content of the brochure and coordination the design, etc. (whatever he needs help with).

We've had four symposiums in each of the last five years. Prior to that we had only one. It's continned to grow. and we've had a lot of tum-over of rna nagers. All this has been challenging. If someone new comes on, I need to travel (to Vancouver Island or Oregon) to train them. (Vic doesn't necessarily attend each symposium.) I needed to attend Silver Falls this year, as it was Mark's first time and I wanted to help.

Now, Lloyd Whannell has managed the Whidbey retreat for tlrree years and will continue, and Simone Weber-Luckham has managed the Camp Columbia Symposium for two years; they both have experience now and do a good job, so that means little supervision.

In the Fall, my job is to make sure that the committees are getting things stirred up.

SS: How much do you participate in the content of each symposium?

VP: Very little. As long as they follow the guidelines I'm happy. Selection (of faculty) has to be done by committee. It's like raising a family: sometimes you don't know what you're going to have to do each day. One major concern is learning to delegate, on all levels.

Publicity, which takes place in winter, now includes a global perspective; using the internet which has proved to be a wonderful thing for us. We've had a number of people contact us because of the NWSSA website.

The Board has recently created the Symposium M~magement Committee. As Director of Symposia, I felt I had a lot of authority, work and responsibility, too much for one person. I wanted more people in on the decisions about how we should manage things. They share authority with me.

I am redefining what I'm doing here. I hope that every year I'm alive I'll be at Camp Brotherhood Symposium, carving stone, directing it, but I want to be there! Because of my plans to move, I need to change my involvement. That's fair to me and to everyone.

SS: Are you investigating other symposium possibilities?

VP: As I've told the Board, I'd like to be part of development of Pacific Rim activity for us, in my retirement. Camp Brotherhood has always been titled an international symposium. So, I could be part of developing some of that scale, like in China, Hawaii, Japan, Viet Nam, or Mexico. We're making contacts in those directions, though nothing is established. My focus for the group would be to do some research and development for other activities for us - for those people who want to go to another country and carve and have an international exchange. I love this development.

SS: From its origins, the events seem to evolve and grow every year.

VP: We've established four significant events. Within that development we've established significant relationships with vendors, with the art community, and with other institutions. The University of Oregon offers credit for the Camp Brotherhood symposium. (There are only two in the country which offer university credit.) We've established a high level of respect and trust among sculptors all over: Japan, across the US, Canada. We're continually getting people from all over.

As far as my vision of it goes, we've all "visioned" it. We've had wonderful input from the individuals that come to us about the structure of the symposium. My role in that has certainly been a key role. The most important thing I always strive to maintain is to have a high quality time for people. It's not "the Association" in bright lights, it's the "individual" in bright lights. We're setting a stage for you to come and be yourself, to be in a trusting environment, to be creative and be supported.

So, as we bring in certain instructors, or develop the program, Of the evening events, we continually keep in mind that we're there for the individual person.

VP: The way I try to manage the committee is to continue to bring in new people to help develop it and give input. Yesterday we had a follow-up meeting from Camp Brotherhood in which four of us on the committee had read every critique. We looked at what worked and what didn't. It was a nice two hour debriefing.

To review our history, we started out for three days in 1987 and 1989. I came on the Board in 1988 and was President in six months. I started managing that second symposium. Since we were a small group, the office and everything was at my home.

When I got the critiques from the second symposium, Tamara Buchanan said three days is not enough, we need a whole week, but we don't want to camp out for the whole week. That's when we started looking beyond the Beyer ranch in the Methow Valley, Eastern Wash. About 30 people were attending at that time. We carnped out and bathed in the river.

About six months later I found Camp Brotherhood while out on a drive. In a few weeks the entire Board came up to see it early in 1990. So, we did a seven day event in 1990 and 1991. We then did 10 days for two years. Then once for 14 days in 1994 and people felt it was too long. We then came back to a 10 day format. In the overall vision, we were trying to give people a long enough time to settle in. Ten days

seems to work.

Every year we make changes. But, we try not to change too much. This year we had the power on some evenings for carving, which worked out well. In the overall perspective, we try to understand what the sculpture community's needs are. The initial objective in '87 was to camp out, carve stone, and have a good time. We brought our own food. We learned.

In subsequent gatherings there was an increasing expectation for this to be a sculpture "school in the woods" (teaching each other). People were invited to teach different topics.

In '91 Vasily Fedorouk came (from the Ukraine) as part of the Goodwi II Games. This opened us even more to entertaining people internationally. So it's been an ever-expanding bubble. As it grew, there seemed to be a synergistic movement in which people wanted to teach and share what they knew. This illustrated the meaning of "symposium" as a sharing of ideas.

Subsequently, we had tool and stone experts come out. So tile educational aspect has been a big push. We have to contain that somewhat because we have to think about the individual person who's coming here to carve, and not be faced with a schedule of workshops all day long. We try to balance this.

We're trying to meet the needs of those who are just learning, people we might meet through the Flower and Garden Show. Or people who come to us from the Whidbey Island experience, from a strictly hand tooling experience, and want to get a broader in-depth experience in one of the larger symposiums. So we always have a well supported beginners program. For others who want something more advanced, we bring in instructors with specialized workshops.

So who is this "one person" we want to keep in mind? They may be 80 years old. They may be eight. We ask, how can we support that "person"? How do we give them a quality experience, welcome them, and send them away enriched? And we do that.

SS: How do you speak to the needs of the more advanced sculptors?

VP: We have a number of members who are active professional sculptors, who've shown to the art community, they've done it. They know how to do it and how to talk about it. We have those people on board to rub shoulders with. Just to be in their presence, to know them, to understand what they've done, to work with them and to see them work.

All this is really important to me. I guess that's why I've done it.

SS: Why is it important to you?

VP: I feel that more than any community I've been part of, the sculptors' community is so tangible and fulfilling. It's very nurturing. This is like my family. I see the important rolc I'vc had in it and the important role it's had in me. So to divorce from that doesn't seem right. I see myself reducing my involvement by 50% in 2000.

We will bring on another person to be Director of Symposia. We want to identify someone to be my assistant to !cam the job. It would be a bridging process over a two year collaborative effOIt.

We need someone who is willing to commit to a long term involvement as a leader in the symposium process, at least for the next few years. Someone with skills in networking with groups, planning art events Of workshops. Someone with a passion for the stone. Someone who has the time and the passion to do this. Someone who's flexible, who understands the symposium concept. It is a paid position (a stipend is negotiated with the Board).

It is going to be important to find the right person. It's going to be a very timely thing. Also, we'll be looking for another member of the Camp Brotherhood Committee.

SS: Many heartfelt thanks, Victor!

The following is an interview with Canadian sculptor Michael Binkley of Vancouver, British Columbia. Here he responds to an interview questionnaire.

Tell us about your life history related to being an artist. Why did you become an artist?

I was born in Toronto, Ontario in 1960, and my father's company moved us to Vancouver, BC in 1966. I have always been interested in art, and had an aptitude towards creating it on paper. I could draw and paint, and got my first set of oils form my grandmother when I turned 12. I loved to paint, and pursued art as an elective through high school. My whole family kept saying "You should be an artist when you grow up." But like many laypersons, I did not think one could actually make a living at being an artist. So, I wanted to become an architect, and chose my education in that direction. However, after two miserable years at the University of British Columbia, I found my left brain was losing the battle.

What key life experience affected your direction in your art?

In the spring of 1980, I decided to take an art history course, offered by Capilano College, wherein the class went to Florence, Italy, to study Renaissance art. Instead of seeing slides of the artworks, we got to go to the cathedrals and museums, and see them first hand. I thought it would be a kick to go, and a chance to get to Europe. It was there that I was introduced to Michelangelo's David, and the four unfinished Captives at the Accademia. Sure, I'd seen pictures, but they can never convey the power of the real thing. I remember returning a few times to sit in front of those four unfinished sculptures, and realizing I could see what Michelangelo was trying to say. It was not until several years later that I recognized that I was actually finishing the carving in my head. I could see the completed sculptures. I guess that was my epiphany, my calling, if you will.

When I returned home, I asked George Pratt (of Vancouver B.C.) if! could work with him for a summer in his studio. He had been in business with my uncle, but at that time had quit the furniture business, and had turned his hobby of stone carving into his career. He agreed to let me work, but in an unusual arrangement. The classic apprenticeship calls for the protege to pay the master. But George paid me to work on his large commissions, doing grunt work, and in the process, learning about tools and stone. In my spare time, I got to work on my own projects. I remember having a devil of a time with my first piece, which was a dolphin. I had so much experience at trying to make a two dimensional surface look three dimensional. Being confronted with a 3D piece of Texas limestone got my brainhand coordination in a knot. But all of a sudden, it clicked. Don't get me wrong, I was not as talented as most of our new members are right off the bat. I look back at my work of 20 years ago and cringe! But it was the best I could do with the experience I had. I was learning as I went.

My father bought my first piece as a corporate presentation gift to an associate of his who was retiring to Florida. I hope that fellow still has it-I put a #1 on the bottom beside my signature. I worked for George for the summer of 1980. During that time, he convinced me that with the right approach, one could make a living as an artist. He showed me how to have your own exhibitions in your home, and how to get into galleries, in order to sell your work. But it wasn't instant success. So, I got a job at a grocery store, stocking shelves -as my "real" job, and worked off-days at George's shop. He was very helpful-I pitched in what I could for stone and supplies, but it was never enough to compensate for what I consumed. Eventually, George had to move his studio, as Expo '86 was being built on the site.

We moved to a location just off Granville Island, and set up a studio/ gallery space. It was very successful, and I managed to contribute more, but it was never a 50-50 split. I guess George really had confidence in me. In the summer of 1985, he told me it was time for me to set out on my own. I've learned so much of the business of sales from George, and am so thankful to him. So, I attribute my artistic career to two people: Michelangelo for the inspirational "why", and George Pratt for the "how".

I bought a house in North Vancouver that backed onto industrial land. My father and I built a small garage studio, and I used the living room as my gallery. That fall, I started my own gallery, Stone Images. In 1987, I had enough sales of my sculpture to support me, and I quit the grocery store job. Now I am a full time sculptor, and the breadwinner of the family. Those bills are a real incentive to get up and at 'er in the morning! Some may criticize me for being somewhat of a prostitute, making sculpture that wi II sell, but I feel that I combine projects that are purely from my heart with those that are commissioned. And hey-isn't that what we all dream for-to be professional?

I'm completely self-represented. I tried the gallery and high end gift store route in the 80's, and some of those outlets worked very well. But none were able to sell enough for me to live.on. In 1986, I started to sell at the local market at the Lonsdale Quay (like Pike Place in Seattle). Every weekend for five years, my wife Michelle and I lugged sculptures and display paraphernalia down there, set up and did our song and dance. We sold a lot of sculpture that way, and trained our clients to come to the house to see more. That, coupled with our two shows each year (the Studio Show in late November, and the Garden Sculpture Show in May) increased OlIf client base to the point where we were in the position to be selfsustaining from sculpture sales. Now I get a call every few months from some gallery wanting to show my work, which is a nice feeling. But they all want to work on consignment, and I can only work with outright purchase, so Stone Images Gallery is the only place to buy my work.

In 1997, we were finally in a financial position to realize a separate gallery to show and sell my sculptures. This has been a real blessing, as it has given us back our private space. We had a 1000 sq. ft. addition built, consisting of a gallery and an office. The space has won praise from our clients, as they feel welcomed and relaxed, making their experience with buying art a pleasure. Our contractor also won an award for his design. The gallery has lots of windows to let in natural light, and to see out into the sculpture garden. The 24' ceiling and exposed trusses give the space the feel of a New England barn, or a warehouse garret loft.

In March, I entered cyberspace with my own website (www.BinkleySculpture.com). I maintain it, and try to update it every two weeks Of so. I've learned the medium is very complex, but it should be worth the effort. Michelle and I track the stats on the site, and so far there are a lot of people looking, all over the world. Kind of eerie. I am using the site so far as a support tool. I get many reqnests for photographs from clients, and the site has saved a lot of time and expense. I'm skeptical as to someone surfing to buy sculpture, but maybe some of those "lookers" will surprise me.

Who and what influenced your artform?

My favourite subject matter is the human nnde. That's Michelangelo's influence. As to other influencesI would have to say "Life". There is no one artist in particular that I could say is an influence on me. I am always bumping into new artist's worksome move me some don't. Just as all life experiences affect one-some influence you to the point of addlng a new slant to your work.

What kind of art do you create?

I divide my subject matter into three categories: figurative, animal and pure abstract. I've concentrated on representational work mostly. My thinking is that until you have a handle on proportion, balance, and line, you aren't going to be able to create good pure abstract art. I tried it long ago-thinking that if someone could splash a blue stripe on a red background, call it "Voice of Fire" and sell it for 1.5 million dollars, why can't I? My first forays into abstract-painting and sculpture-were terrible. I feel more confident in my representational abilities now, and so am finding most of my abstract compositions are pleasing, or at least better.

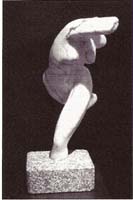

A recent interesting project was the transformation of an earlier piece. I did a life-size sculpture of Eve in the Garden of Eden, just after she had bitten the forbidden fruit. She was seductively posed, the apple concealed in her left hand behind her back. The serpent was coiled about her feet, and reaching up to lick the apple. I called it the Temptation of Adam. Loads of symbolism. Few viewers got it. They didn't.walk around the sculpture.

I was happy with her when I finished it. But as the years went by, and I became disenchanted with her, I thought I'd rework her. So off with her head, her legs, and arms! She got a spine, lost weight in her butt and hips, and I plunked the apple right there in front of her. Voila, Temptation of Adam II. A much more dramatic sculpture, and everyone gets it now.

I've been asked, why torsos, and not complete figures? I like the expressive power of the torso. I find that the whole figure can sometimes negate the expressive power of the torso, especially in stone. I think the whole figure lends itself more to the medium of bronze. One of my clients said she does not like figures with a head and face, as they make her associate them with someone she might know. She prefers to complete a torso's limbs and head in her imagination. I agree with her. Temptation of Adam is a good example.

Another recent piece is "Torsion". I used a piece of Jim Gill's "magic"pink alabaster. (He calls it magic, as anything I make from it sells first at an exhibition-until now!) Tbe female torso is quite nice, in a twisted composition. . But what Michelle noticed is that there is an unusual amount of negative space in the piece- more than] have included in the past. I call it "pushing" the stone. But I don't want to go too far. I like to keep the "stoniness" in my sculptures.

How do you develop ideas?

I direct carve almost exclusively. I never leamed the process of doing maquettes first, so have not pursued that route. I wi II, however, make drawings for a client first to help them to better understand what I will carve for them. And if I ever get that big commission, I'll for certain make a maquette or two to get the kinks out. I just find that with most stones, one cannot be certain of what's on the inside of a block. I would not want to be tied down to a blueprint model, as the stone may have an interesting veining happen deep inside that would encourage a subtle or drastic change in composition. As T mentioned, I see the finished sculpture already before I begin, and just take away what's not supposed to be there. I see the end result, as opposed to seeing it develop along the way. I guess I see what the stone is saying to me, and go after it. For the most part, I don't spend a lot of time communing with a stone before I begin. I'm quite brutal. I look at a piece, decide quickly what I'm going to create, and get down to it. I'm impatient, so I like to finish one piece before starting another. Every now and then, I get itchy to make a largish piece on spec, and then I will have it ongoing as I work in tandem on smaller projects. I must always think of those bills, so the commissioned sculptures always take precedence.

What size or scale is your sculpture?

I work in scale from something that will fit into the palm of your hand, to something that will fit into a park, or plaza. I prefer life size to about half life size scale. This affords me the latitude I like to create, but I still have a way to go to be able to subsist on the sales of those scaled works.

What stone do you prefer to carve?

I like all carvable stones. I stay away from soapstone for its stigma. There are a lot of folks who think that the only sculptors working in stone today are Inuit, and that they carve soapstone. I love marble most, particularly statuario. It has an integrity, crystal structure and workability that I've not found in any other marble.

What tools do you use?

I mostly use diamond abrasive tools-angle grinders, bench grinders, die grinders, etc. ( I've yet to try the hydraulic diamond chainsaw ... ) If I'm working on a larger piece, I'll use pneumatic chisels. I like the sensation of the chisels-they seem to be the "real" way to carve. It's just faster to remove stone with diamond. (He says he's interested in the possibilities of the high pressure water cutter for stone.) My impatience precludes my using hand tools, but if all I had to do for a few years was the great piece, and there was no deadline, I'd dig into a Carrara quarry block with hammer and chisel.

How much sculpture do you complete in a year?

If you include all the flower vases, and small animal and bird sculptures, I produce close to 200 sculptures a year. I figure I've made over 5,000 in my career (one contract alone for a Japanese client was for 1,000 white dove sculptures!)

Do you teach?

I don't fancy myself a great teacher. I do workshops at the NWSSA Symposiums, but aside from that, I don't teach. My shop isn't big enough for classes, and the city zoning would not permit it anyway.

Why is art important to you?

Being around art-paintings, sculpture, architecture, music, prose - is an essential for Michelle and me. Art communicates from one human being to another on an emotional level, as opposed to a purely mental level, such as most technology does. Creating art is essential to me. I think that is what is meant by the saying "an artist must suffer". It's not that we have to endure physical hardship (that happens to everyone). The suffering is that we artists need to create-we can never turn it off. We are always thinking out the next sculpture in our heads. It's not like other jobs where one can walk away after a 9-5 work day. Our work follows us everywhere, all the time. Now fortunately for me, my "suffering" is not a hardship. I just get annoyed when I get a great idea, and can't get hold of a piece of paper and pencil to write it down or draw it!

What is your relation to NWSSA?

I joined NWSSA in 1992, at the suggestion of George Pratt. I'm so glad I did. I've met so many wonderful people, who share my same insane passion for getting extremely dirty. All for the love of trying to make a rock look a little more beautiful. I am humbled that there is so much talent in our organization, and I am honoured to be among you all. I love the symposiums, but cannot get to them all. Unlike some of the members who make the symposiums their holidays, this is my work, and I like to vacation where there isn't a chisel around ... I have been an instructor at workshops at past symposia, and will again insttuct at the September '99 Thetis Island Symposium. I will come to Camp Brotherhood (July '99) for a day trip to visit.

What is your life philosophy? How does your art reflect that?

We are here to be the best at whatever we can do, and to enjoy our time as best we can on this earth-plane. If we are to be shit shovelers, we should be the best damn ones around. Never risk more than you are willing to lose. Take baby steps. Always observe-never stop looking. I try to approach life in a very pragmatic, and realistic way. I try to set realistic goals, and go about achieving them in a practical way. I love to carve stone, the process of removing what I don't feel should be there to realize what I hope is a beautiful artwork. If it brings pleasure to someone else, then my accomplishment is enriched. I am not into making big political statements, or exploring sensitive issues. I just feel that I want to make a small corner of the world a little more beautiful.

My wife and I are blessed with curiosity. We want to explore as much of this earth as we can while we are here-the physical locations and the emotional responses they lnspire in us. If we had the financial means, we would go to as many places as we could. But by the same token, we are very grounded in our home environment, and love to be here. Our house and garden are our sanctuary, and we feel whole when here.

What have been your satisfactions in your life as an artist?

Being able to play every day and get paid for it. Getting my hands to do what my mind and heart see. Hearing from a client how much they enjoy my work, how the piece has affected them, and having them caress a piece of my sculpture.

What have been your obstacles or challenges?

Still not having been able to do the great piece. I have wooed clients for almost 20 years, and still haven't gained the confidence to have a large sculpture commission. I see more and more cities adopting public art programs and bylaws which restrict my ability to directl y sell to "tall building clients". Instead, open competitions are the only option, and while on the surface these might look like great opportunities for artists, they really are not.

Art by committee usually results in mediocre (at best!) art. These competitions are so wrought with problems and elitist mentalities that the public they are supposed to serve gets forgotten. The competitions are usually directed by a government body (municipal or state/ provincial), and are another example of how government should really stay out of the way of private enterprise.

What are you looking forward to (goals, wild ideas)?

If things go surprisingly well.... Finally winning a competition! My record is 0-71, with two more in the judging stage. Also to go to Pietrasanta for a month and carve statuario marble in one of the studios there. Many of the members have done it already, and I salivate over it. Another goal is to rebuild my studio. I have a much better understanding of what my working needs are, and the tools I use have changed since I built the first one, so I would like a different setup.

Cheers, Michael

This granite sculpture was installed by Candace at the entrance of the Santa Fe Farmers Market building in the recently refurbished Rail Yard Complex in

This granite sculpture was installed by Candace at the entrance of the Santa Fe Farmers Market building in the recently refurbished Rail Yard Complex in  The design she had selected for Replenishing the Earth required stacking stone up to 11 feet, 3 inches. And since Candyce works alone it took her four and a half months to complete. The fastening together of all the pieces required fifty 7/8 inch stainless pins. After the assembly, Candyce took it all apart, loaded it onto her 20 foot long flatbed truck. Then it was off to the Farmer’s Market in

The design she had selected for Replenishing the Earth required stacking stone up to 11 feet, 3 inches. And since Candyce works alone it took her four and a half months to complete. The fastening together of all the pieces required fifty 7/8 inch stainless pins. After the assembly, Candyce took it all apart, loaded it onto her 20 foot long flatbed truck. Then it was off to the Farmer’s Market in

Editors’ note: While it may be true that Michael is a beginner at stone carving, he is no fledgling in the art world. Michael routinely adorns human skin with amazing creatures of his own design at the Tattoo Garden on 2nd street in Everett, Washington.

Editors’ note: While it may be true that Michael is a beginner at stone carving, he is no fledgling in the art world. Michael routinely adorns human skin with amazing creatures of his own design at the Tattoo Garden on 2nd street in Everett, Washington. I had always envisioned the sculpture to be more abstract, like just the dorsal fin of some sea creature but when I actually put the stone on the bench, I just couldn't find it again. My normal start to any sculpture is just to find a main curve or direction in the stone and start removing material to reinforce it. That's one reason that I do a lot of my initial removal by hand, because it gives me time to continually look at the shape that's developing.

I had always envisioned the sculpture to be more abstract, like just the dorsal fin of some sea creature but when I actually put the stone on the bench, I just couldn't find it again. My normal start to any sculpture is just to find a main curve or direction in the stone and start removing material to reinforce it. That's one reason that I do a lot of my initial removal by hand, because it gives me time to continually look at the shape that's developing. In recent years I have pretty much worked on smaller pieces mostly made from Gary McWilliams Alaskan Stone. I have found that these pieces sell well in today’s market. Since

In recent years I have pretty much worked on smaller pieces mostly made from Gary McWilliams Alaskan Stone. I have found that these pieces sell well in today’s market. Since  As of the first of this year I’ve moved from my

As of the first of this year I’ve moved from my