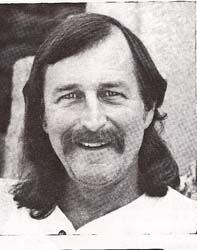

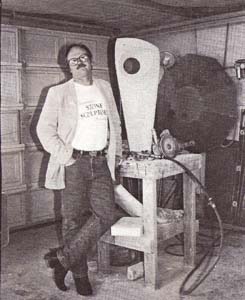

This is an interview with sculptor Michael Jacobsen at his home and studio in Bellingham. WA, where he lives with his wife Carol and daughter Britt. Michael is a current NWSSA board member and chairs the exhibition committee. He has been working full time on his sculpture for the last year and a half after having left a career as a museum exhibih"on designer. He has previously been a print shop layout artist, skippered a sailboat, been a ranch hand, ron his own sign business, and managed a university art gallery. He hold a BFA degree in sculpture. He is a kind, thoughtful person with a deep sense of spirit and connection to the Earth. He is also a prolific sculptor. We start by viewing his portfolio.

MJ: (Looking at his "Norse Sea Rising" of black Belgian marble approximately 42"h x 19"w x 8"d). This piece started out as a representational dorsal fin of a killer whale. As it progressed, it evoked the shape of a Viking ship prow so it merged in between the two. In the same fashion that the prow of a ship cuts through the waves, a killer whale cuts through the waves. This created the idea of the symbolized wave or curl. To me it has more symbolism than that. I'm also exploring the Celtic and Viking imagery. With the Celts, there are lots of curvilinear elements.

SS: Did you start with a conscious desire to explore that theme?

MJ: The desire started with wanting to do a killer whale fin. This gets into an explanation/exploration of what I call .. Earth-hased roots." I saw an exhibition of Native American work in which the artist, Marvin Oliver, did a beautiful, stylized sculpture of a killer whale. It had all the native symbolism on it, with strong curvilinear design elements. I was struck by the power of that singular image of the vertical killer whale fin. I suspect, to the seafanng people, It must have been a near mystical image.

I used to feel cut off from being able to do that kind of imagery. If you do a killer whale dorsal fin, it's difficult for that not to look Pacific Northwest Native American. We have to go a little bit further back in history than Native American to find our roots. but my Earth-based indigenous roots are in Northern Europe. All of the Earth-based imagery I could ever want is alive and well there.

SS: Is this your major drive, your major theme in your art?

MJ: The connection between my pursuit of spirituality and my pursuit of art is paraJIel. They're inseparable. It's hard to taJk about art without flipping into a spiritual conversation.

SS: Is your art a natural outflow of your state of being and belief? Or is it a more conscious process in which you choose to express something?

MJ: You're asking BIG questions (laughter). So why do I do art? I relate that to the day-to-day basis of "what do I most want to do today?". What I most want to do today is to make art. And out of that comes a pursuit of a meaning for life. In a word, the important thing for me is relationship; the striking of a relationship between the material and me. Many of ns taJk about various stones and their qualities. In the Association, there are many who seem to have a love affair with stone.

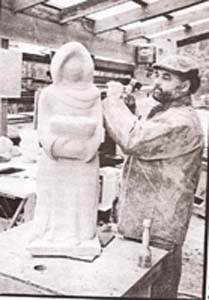

Most of us who do direct carving work at various levels to pursue that direct relationship. In the same way you read a book, you read a stone. Sometimes it has dominant themes. That leads you in a direction. If you follow that direction and you make a move or a cut on the stone, that , changes the landscape, the relationship. Then you make another move and so on, there's a continual dialogue. (Michael quotes a William Michael Jacobsen IStafford poem.) ... each rock says 'your move,' then waits until you do ... You make a cut then it's your move again. So you're continually having this relationship with the stone until you feel the sculpture is completed.

SS: Is most of your work direct carving?

MJ: Yes. I have never made a model with the intent to go find a stone and make the piece fit the model. If I've ever made a model, it's only to help me clarifY confusion about what I'm seeing in the stone during the process.

SS: How do you develop a relationship with a stone that doesn't have a predominate shape?

MJ: If you bring me a cube of stone, I don't know what to do with it. My preference is to be attracted to a stone initially. I don't have to worry about it then. In the world there are so many attractive stones.

If you bring me a cube of stone, I don't know what to do with it. My preference is to be attracted to a stone initially. I don't have to worry about it then. In the world there are so many attractive stones.

SS: Does that process work in the realm of cominissioned work?

MJ: I think it can, depending on how much freedom you're given in the process of the commission. The client has to realize that there might be changes to the original idea along the way. A time comes to mind when the commission became a piece unrelated to the model. That was acceptable to the client. That process allowed for a better piece to emerge. It gives the flexibility that's needed when working directly with the material to alter and move in the direction that the stone might lead you.

SS: (We visit his current show, "Elemental Earth," at the Blue Horse Gallery in Bellingham, W A.)

MJ: This show contains a series of pieces entitled "Stones of the SkY" after a book of poems by Pablo Neruda. Written at the end of his life, he was writing love poems to the Earth. The things he realized he was leaving behind and simultaneously going towards were stones. The depth of his relationship with the mineral world was amazing.

SS: With character stones like these, do you try to consider a more involved composition?

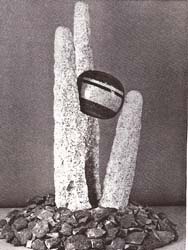

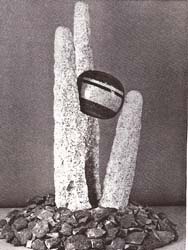

MJ: I generally try to create very strong shapes. In this case, the stones didn't allow me to do that. So this is an attempt to collaborate with the material. If you're truly collaborating with the stone, it's a dance between the two, the stone and yourself. Sometimes there's a battle of wills between what the stone wants to do and what you want to do. These stones were very powerful teachers for me in the sense of making sure my collaboration was minimal. These stones did not want to be cut radically. "The Philosopher and Students" has another dimension to it. I was taught quite a lesson with these stones. I found them on a beach at low tide and hurt my back very badly while loading them into my canoe. Among other things, they taught me how to ask for help.

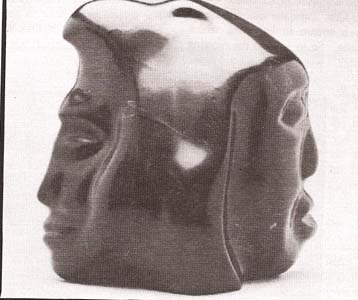

The "Sentinel" sculpture is named after a place (in the Cascades) whcrc I go on my annual, solo, wilderness "spirit quest." There is a pinnacle of rock in a canyon that is a 'er, imponant place for me. This sculpture is an honoring of thai place. (We look at "The Philosopher and Studcnts." a five-stone grouping set in a bed of small stoncs) I found these stones four years ago and I've been looking at them for that long and placing them in many interrelationships. I ended up doing the most minimal amount. This large stone seemed to be a dominant stone and had the look of a monk with a cowl. I couldn't find myseIf making a major cut on any of these stones. So I made facets or "faces" in the natural stones.

SS: Is your experience of doing fully formed sculpture and minimally formed natural stone dramatically different?

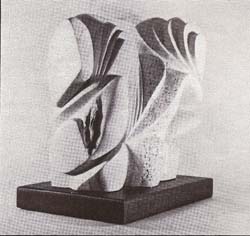

MJ: They have their roots in the same process. "Jupiter Rising" (a fully sculpted form) was made through a series of decisions and moves that led from one step to the next along the path to the finished piece. The "Philosopher and Students" was saying "I'm just fine, thanks; you don't need to do anything here."

Thcre is already a huge audience out there who is as interested in stone as we are. When something is obviously about "stoneness,"-the qualities of stone-then that can become a focus. The artist opens a door or access point to the art. Sometimes it is a representational form. Sometimes the beauty of the stone itself is the open door that will draw in the viewer. Sometimes the open door is a sensual shape. Sometimes it might be a polished surface that attracts their eye and they reach out to touch the stone. There are many ways that artists have to create "open doors" for the viewer.

My intention is to communicate with the viewer. I want to find those access points that open doors which allow a viewer to come into a relationship with the work I do. I consciously attempt to allow those access points. Then I have to release it, let it go. Quite often I'm surprised how a piece I do, that has a certain intention, matches up with a person who is receptive to the same intentioll. There is magic that happens in that process. (He tells of a sculpture, "Tree of Life," which synchronously was chosen to honor a man who was responsible for acquisition of forestland for county parks. It is installed at Big Rock Gardens, Bellingham, WA.

Another experience of synchronicity was with "Phoenix Rising." I originally saw a bird shape in the stone (portoro marble), but was frustrated by all the color in the stone. I awoke one morning realizing that the bird could be the Phoenix and that the color could be the flames, with the bird coming up out of the fire. At the same time, due to job stress, my doctor said I should get away from the work place. While on medical leave, I went to the stone and started developing this idea. In the process of working on the shape of the Phoenix, I was also, in a parallel way, working on my own internal Phoenix that was rising. It was so powerful it brought tears to my eyes. This is the fine tuning of the creative life; being able to create your life in the process of exploring your creative ideas. That process led me to doing art full time and I never went back to my previous job. That magicaJ relationship with stones happens infrequently, but it happens enough to make me want to continue.

SS: (We view his jade "Paleolithic Ceremonial Adze. ") I want to explore the idea of the ancient hand tools more. Jade was used frequently because of its resiliency and strength. There's a granite piece at Gallery Mack in SeattJe entitled "Neolithic Altar," paying respects to a hand adze in a large scale. The desire is to recapture some of that initial connectedness that the Paleolithic or Neolithic humans had with stone.

(We look at "First Sacrament" in which a basalt form in the shape of an adze hangs from a wood tripod over a ceremonial stone altar.)

SS: What is your preferred working process?

MJ: If I had my druthers, I'd have thirty pieces going at any given time. If I get disappointed or discouraged with thc piece I'm working on, I just take a break, walk around, and work on pieces I'd previously started. Or I might start an entirely new piece. I eventually get back to the pieces I'd worked on before and finish them up.

A gem of wisdom that JoAnne Duby gave us at the '98 symposium was to consider the base as an integral part of a piece early on in tile process. With each piece (in his current show) the base becomes a connector with the Earth because the stone came from the Earth. I've taken them from the Earth and set them in a pristine gaJlery setting. I want the base to relay a sense of its connection with the Earth. My preference would be to have sculptures that are outdoors and are literally connected with the Earth.

SS: What scale do you prefer to work in?

MJ: If you have something you can pick up and put into your hand, that piece comes into your space: there's an intimacy there. The same thing with larger scale works. They can fill your peripheral vision: thcy become present with you in your own space. In a different way, they have an intimacy about them as well. The mid-sized pieces that sit on a pedestal and are too heavy to pick up, create a kind of a distance. To me they lack that intimacy. So I like the small and the large-scale pieces best.

SS: What is your involvement in NWSSA?

MJ: I've been on the Board of Directors less than a year and we've been working mostly on our organizational structure. We're in transition, becoming a more professional organization, refining goals and objcclives. Our challenge is to continue to incrcasc the support and opportunity for the advanced and professional artist, while maintaining our supportive environment for beginners.

SS: Many thanks, Michael.

The following is an interview with Nicky Oberholtzer. Nicky has been a NWSSA member since 1990 and has been an instructor at the Whidbey Retreat and Camp Brotherhood Symposium. She is a graduate of Seattle Pacific University. I visited her at her home in Seattle. She did not have a photo of herself available for this interview, but the essence of Nicky is clearly shown by her work and her responses to my questions.

BL: What led to your becoming a sculptor?

NO: A teacher named D'Elaine Johnson. She was my high school art teacher and really inspired me to do whatever I wanted-just to respond to art forms, to enjoy forms. As a consequence, I wanted to be an artist. When I graduated from high school, my dad asked, "What do you want to do?" I said, "I want to be an artist." He said, "No, you can't do that. You can't make a living at it." I am here to tell you he is right (laughter). Because of that I denied I was an artist for years and didn't tell anyone I did artistic things. I was always doing art in some form. I went to Sweden to learn weaving for a year. I didn't hide my artistic interest very well apparently, because one day in church someone suggested doing something creative Everyone turned and looked' at me and I thought, "You're doing a really good job of being a closet artist." That was the beginning.

At one point, my husband and I made a career change. We asked ourselves what we wanted to do and decided to stop working for other people and start working for ourselves. He decided to become a contractor; I became an artist. At that time I was going back to school for a psychology degree. I wanted to do art therapy. The nearest good degree program was in either Idaho or Oregon, which meant uprooting my family, and I didn't want to do that. So that went by the wayside.

BL: How did you know that sculpting was what you wanted to concentrate on?

NO: I needed certain art credits and thought sculpture might be interesting. I took one class in sculpting and the stone just grabbed my soul and that was it. I changed my major to art and graduated with a BA in Fine Arts and a BA in Russian.

BL: Were there other art classes at Seattle Pacific University that were helpful?

NO: A teacher there named Larry Metcalf is absolutely wonderful in teaching design. And I also took oil painting and I still do that and pastels. I did stained glass for ten years before I went back to school.

BL: Besides sculpting, you have done oil painting, pastels and stained glass. Anything else?

NO: Clay and basket weaving. I can't go without doing something creative at least once a week or I go nuts.

BL: What is your favorite stone to work with?

NO: I enjoy yule marble, but I hate the sanding process. I enjoy chlorite. I do a lot of alabaster, so I guess I would have to say alabaster, but I do like yule marble because of the purity of the color-the whiteness.

BL: What stone did you work with at SPU?

NO: Alabaster and soapstone.

BL: So you were using hand tools only at that time?

NO: The first class, yes. By the time I left SPU, I had been introduced to the angle grinder at a symposium.

BL: [A cat walks by] I know you like cats. Do you do any sculpture related to cats?

NO: I like to catch cats doing what they do. I don't like trite poses. I really encourage beginners to stay away from trite poses such as the cat with the legs out front just sitting there. If you are going to do that, make it interesting. Find some other way of presenting it.

This cat is annoyed and he has decided he is going to ignore you. Cats turn and pretend to preen themselves, but they'll let you know they're annoyed by putting their ears back. This is what I tried to capture. I'm pleased with the result.

BL: Is that a fracture in the stone?

NO: No. those are black inclusions in the stone. It hasn't been cracked. It's a gorgeous stone, but one I wouldn't use again.

BL: To me it looks like a very old piece. Like they would have done in some Chinese dynasty.

NO: Oh really. Thank you.

BL: Do you prefer working with abstract or realistic forms?

NO: I work with all of them. I talk to people who say you should stay with one or the other. I basically do what I am inspired to do. Sometimes the inspiration is from the stone. I see something in the stone and it cries to get out. Other times I find a form I like and that is a starting point. I'm a direct carver-I'm not a maquette carver. Occasionally I do drawings. Sometimes I stick to the drawing, but more often deviate considerably by the time I'm done with the stone. I let inspiration guide me.

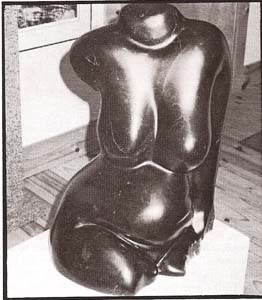

NO: The word abstract means that you have to have known the original form in order to abstract it. You have to be able to do a good torso in order to be able to simplify it. Otherwise you are not usually going to do an effective piece. Some people are exceptions, but the majority of sculptors do abstract because they don't think they can do a good torso or animal and they are kidding themselves. I do abstractions a lot. Usually human form or animal form. I do a lot of stylized forms. I like to do human torsos that emerge from the stone and merge back into the stone. But usually my abstracts have a basis like this piece [pointing to a piece]. It started out being a leaf and when your husband [Ward Lynch] looked at it, he said, "I see a frog there." I talked to four or five other people and I got at least six different forms that were in that piece that I didn't know were there. Subconsciously I probably knew they were there.

BL: Are there sculptors, living or dead, who have influenced your work?

NO: Yes, Georgia O'Keefe, Henry Moore, Brancusi, and Everett DuPen to a certain degree.

BL: Your least favorite part of sculpting is sanding?

NO: Actually not. That's why there's a TV in my studio. When you get to the sanding part, it's a no-brainer, so I just turn the TV on and zone out on some kind of show. Or I talk to somebody when I'm sanding or carving. That's why I like to do Artists in Action. If I know where I am going on a piece, I usually end up getting it roughed out by the end of the day. I'm talking to people and I don't notice I'm working. The inspiration process is actually subconscious-I'm not aware I'm doing it. Sometimes I get home and look at the piece and say, "Whoa, that really changed!"

BL: What is your favorite part of sculpting?

NO: It's that point where what I see in my head is realized. When I see the stone actually taking on the form that I envisioned or something even better. That, and sanding everything but marble. I haven't found any tools that do a good job sanding so I always come back to doing it by hand. I do use diamond sanding pads. I have all the fancy sanding tools, but they sit in my closet and don't get used.

I'm a color-oriented person. The other part of the process that I really enjoy is when you're working a piece that is dusty and you don't see the color. Then as you start sanding, things start appearing that you didn't know or didn't remember were in the stone. I like that journey of rediscovery and seeing what the stone does in conjunction with the form.

BL: Do you select your stone and look for the form in it or have an idea and then select the stone?

NO: More often than not the stone tells me what it wants to do. I look for stones that talk to me-that inspire me to see a certain form within. The stone guides me in where I'm going. However, there are times when-like the piece out on the deck that is three-quarters finis~I drew a picture and then realized it was within a stone I had.

BL: Do you bave any pieces currently in shows?

NO: Oh, yes. I bave pieces in the Issaquah Gallery, a gallery in Colorado, and one in Bellevue: I have a piece in Pioneer Park in the Puyallup Outdoor Sculpture show-a moon-shaped piece oflimestone that has a face with it's mouth open and it's on a triangular piece of granite. It's a birdbath.

BL: You have been to symposiums in Colorado. Tell me about them.

NO: I like Colorado, as everyone probably knows by now. You carve in an aspen grove at 9000 feet. It meant tbat I had to be on my own and that's a first in my 24-year marriage. I learned to work yule marble. I still don't feel totally confident working it. Marble/marble is a wonderful workshop for beginners all the way up to advanced. I would recommend going with some knowledge of the tools because they use a lot of power tools that are huge and can be terribly intimidating. The quarry is right there. If you ever get the chance to go into a quarry, it's really inspiring.

BL: What does your family think of you doing sculpture.

NO: The kids are annoyed when I go away for workshops because they feel it cuts into their summer. I have a 20-, a 17- and a 14-year old. They are very suppottive about what I do. I even occasionally hear, "Oh, I really like that, Mom." My husband has been an absolute charm. He is the most supportive person in the world. When I get discouraged, he's there to say, "You're doing what you're supposed to be doing. We decided that, now keep on doing it."

I've talked to so many women who were taking art classes at SPU whose husbands were ridiculing them or dissuading them from doing art. I felt so sorry for them and realized how really fortunate I am. I really do feel I have a talent that God has given me and I hope I am blessing Him by using that talent my main life goal.

BL: How much of your work is done with power equipment versus hand tools?

NO: The roughing out portion is done with power tools and then I go to hand tools unless I'm doing an artist in action where you can't do power tools. I get really frustrated in not getting close to the form. I attend a nude modeling class, started by Everett DuPen at University of Washington, but now on Mercer Island. When I go to that, I do basically hand tools. It is a good discipline. You get locked into getting to the piece too fast and need to have that discipline to realize that the stone is resistant and it is not always going to do what you want it to.

BL: How do you know when is a piece is finished?

NO: Usually when the vision I have in, my head is satisfied. Occasionally I'll think a piece is finished and it's not. For example, I have a show of animals in an Everett gallery and I had just finished a large turtle I was working on at the last symposium. I put it in the show and I looked at it and it's not right. It's

finished technically, but I don't like it. There is something wrong with it and I've got to figure out what. So I will probably bring it back and stare at it for two or three months before I touch it again.

BL: Does intuition play a part in the process of your sculpting?

NO: Oh. yes, very much. Without intuition I would be a lousy sculptor. I think my carving is intuition mostly. And again [ think the stone talks to me.

BL: Tell me about your goals.

NO: I want to do monumental pieces, just like everybody else. Right now I'm restricted by what I can lift and my lack of tools, but once I've invested in a hoist and some other large moving tools I'd like to work life size or larger. Actually I'd like to do a couple of ex1remely large pieces. I'm doing 3 twisting sea serpent/dragon in clay right now that someday I'd like to donate to Utah to be installed on the salt flats. Driving across the salt flats is so boring, it needs some visual interest. I'd like to do it in basalt and the head would probably be about as tall as I am. That's one of my goals.

I'm working on a piece from Marble! marble. I've been basically stymied and unable to work on the piece because the top part weighs about a ton and the bottom is about 12,000 pounds. I don't have the capacity for lifting it and pinning the base. I'm hoping it can be done at the symposium with the help of some of the equipment that is up there. It's shaped like a harp but, rather than having strings going though it, I'm opening up curlicues on one side which represent harmony and will hopefully open it up on the other side to appear like musical notes or something relating to music. The idea behind the piece is the harmony and music of life. I think it will be an excellent piece when it's done. I have really enjoyed working on it. I am excited about seeing the end. It has been driving me nuts just sitting in my driveway.

Another piece I'm working on is related to the piece installed in Puyallup. It's called "Loony Moon." Again, a crescent moon and a birdbath that trickles down to a little pond underneath. It stands about four feet tall. I like to install humor in my pieces. That's a real important component. I think pieces can be humorous and yet be a serious art piece. I think sometimes we need to laugh at ourselves. We need to laugh at the world.

BL: Would you say your "Frog With an Attitude" is an exanlple of showing humor?

NO: Yes, it's a one of a series that I am doing. The whole series will be called "Frog With an Attitude." The one on the lily pad was the first and was done about seven years ago. What I'm doing is taking human attributes and attitudes and putting them on frogs with the idea that when I get the whole exhibit done, people can go in and laugh at themselves. I have a couch potato frog sitting on a sofa with a beer can in one hand and a remote in the other. I have a frog with a great big grin called "What Are You Smiling At?" I'm going to do a road hog frog. A motorcycle frog. Sew a vest and have a bandanna on his head and cigarette and really have an attitude. I am hoping that people can celebrate life by laughing at themselves.

BL: Your dolphins are an example of one of your realistic pieces.

NO: That piece took fourth place at the Puyallup Fair about four years ago. It's only about 7'x7'x 8". It's a piece of marble from Canada. It was a very fractured piece. People say you shouldn't glue stone together. It has been glued together about eight times and you can't tell. It shows how a stone can be fractured and still turn into a wonderful piece without jeopardizing the design. It took me over a year to do because there was so much damage to the stone. I had so much invested in it that I really couldn't let it go.

BL: It looks shiny. Is there some kind of finish on it?

NO: Typically I use waxes, although I'm trying to get away from that because waxes eventually yellow andif the pieces aren't dusted regularly-the dust tends to work its way in and dull the finish and require the piece to be refinished.

BL: Tell me about "Peace."

NO: This is from a series. I have two series goingthe frogs and the leaf series. This piece started as a leaf form. What I would like to do one day is have a form show. I love nature. I love the variety in nature-in leaves, in flowers. That is probably what got me going. The idea is to take the leaf form and twist it and turn it. Move it in different ways but keep the idea of the leaf. I usually put some kind of an opening. I did one called "The Wave." It's a leaf form that is curled over on itself and looks like a wave, too. Eventually I would like to have thirty pieces, each done in a different stone-both indoor and outdoor pieces-in a leaf form. Its organic and much of my work tends to lean toward organic forms. Centered in each form is a naturally rounded river rock. The leaf form is something that I have created and the river rock is something that God's created.

BL: Do you ever have to go into a library and research for any of your pieces or search for pictures?

NO: Yes, I do a lot of research actually. One of my best sources, and I urge beginners to do this, is go out to a Goodwill store and pick up National Geographics on whatever topic you do. Take them home and cut them up and create a file system for yourself. I'm doing a Puma Man right now. I'm not sure where it came from. There is a legend of shape changers-half man, half animal. This Native American brave is turning into a puma and it is in the middle of the change. The head is a puma, the shoulders and the upper arms will be man and the hands will be paws. It's not something that I have done before. It is a branching out for me. In order to do the puma face right, I went out and researched cats.ln order to do the chest right, I went out and got a Playgirl because it is very hard to find good male models that are built like I wanted this figure to be.

BL: Would you like to give me a statement of your philosophy?

NO: Celebrate life. I struggled for many years trying to figure out what I'm trying to say; what my heavy message is. What penetrating thought do I want to share with others? The one thing that we don't do is really look at life intently. In order to do a bird, you have to spend time looking at it. I go to the zoo and the aquarium and spend hours staring at subject matterhow they stand, how they turn and twist, how they rest, how they swim. I try to capture that life in my sculpture rather that just doing a static form. In order to do that, you have to learn to love the form and to understand it. There is a celebration of life that seems to come out of that study.

Go to a nude modeling class. Study the human form. It is fascinating. You'll never see the same form twice. It's an endless variety of shapes and colors and sizes.

BL: How has NWSSA influenced you?

NO: It has been great. I have learned a lot. What is so valuable about it is the networking. Also the access to tools, information about tools and stone. One of my biggest frustrations in 1990, when I was getting started, was finding stone, so I started acquiring it myself. Because of this, I have learned a lot about stone. Going to the symposium is like being in an encyclopedia on stone and tools. You visit other peopIe's studios and you learn so much seeing other people's processes at the symposium and getring tips on things. I like the friendliness. When I joined the Northwest Stone Sculptors Association-I know nobody is going to believe this-I was extremely shy. The Association helped me open up and be who I want to be. I would encourage people who go to the symposium to be gentle with beginners. They are very fragile.

BL: What things do you teach?

NO: I teach hand tools, pneumatics, design, and paper making. I have also been asked to jury at the state fair this year. This is the second time they have asked me. The first time I couldn't because I was going to be gone. It is really an honor to be asked.

BL: Do you suggest people start with power tools?

NO: One thing about sculpting is that it is a series of stages. People start out usually (there are exceptions to every rule) using hand tools, go to electric tools, and graduate to pneumatics. It doesn't have to be in that order but often the cost dictates the way you have to go.

I look at sculpting as a series of goals and steps. This year I have realized two goals. I have a piece in Puyallup that is a step towards a monumental piece. My other goal was to be asked to judge a show. That was a goal that I didn't expect to achieve for a number of years. So now I have to ask myself, "What is my next goal?"

BL: Thanks, Nicky.

Editor's note: because of the length of this interview, parts of it were cut for use at a later date.

This is an interview with stone sculptor/artist Verena Schwippert at her

This is an interview with stone sculptor/artist Verena Schwippert at her

d realized this was the artist who has fully captured the inspiration of what this piece could be. He was like a mentor to this commission happening. I have no cultural connection to native people. I needed something to connect me with their art. When I saw his work, it inspired me. That then led to me carving, at the Vancouver Island Symposium, this most recent piece (approximately 20" x 15" x 12" entitled "Proud To Be Me" - a native woman seated with a water urn, wearing beads, and carved from chlorite. This person just "showed up". I didn't do facial studies; I direct-<:arved it. After doing the research around the commission, there was an impression made in me. I just went out and I carved She has that look of being proud to be who she is. I will also use the direct carving approach to this commission instead of pointing up from an exact model.

d realized this was the artist who has fully captured the inspiration of what this piece could be. He was like a mentor to this commission happening. I have no cultural connection to native people. I needed something to connect me with their art. When I saw his work, it inspired me. That then led to me carving, at the Vancouver Island Symposium, this most recent piece (approximately 20" x 15" x 12" entitled "Proud To Be Me" - a native woman seated with a water urn, wearing beads, and carved from chlorite. This person just "showed up". I didn't do facial studies; I direct-<:arved it. After doing the research around the commission, there was an impression made in me. I just went out and I carved She has that look of being proud to be who she is. I will also use the direct carving approach to this commission instead of pointing up from an exact model.