Kirk lives on 10 wooded acres in the Arlington, WA, area with wife, Judy Burnett, and two joyous golden retrievers who made sure I noticed them. They built the super insulated, energy efficient solar house and studio, so Kirk was able to design to his needs. He says, “Since we moved to the property, my day job has been taking care of the property and trying to raise as much of our food as possible in the large organic garden and orchard. This has kept me very busy, but gives me a flexible schedule so I can tackle sculpture projects when they arise.” The studio includes an inside workspace (20’x16’) with a large workbench for stone carving, welding, and other dusty tasks, and a heated “clean” room for drawing, modeling, working with cast paper and the like. He does his wet carving outside.

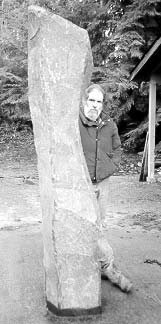

We start talking about his 8-foot high, gnarled basalt column (from Yakima, WA), which is standing on a concrete pad outside his studio. Above it looms his 14’ high mobile gantry rated for 5 tons. It is fitted with a two-ton chain hoist. This makes me think something Big is happening.

SS: Kirk, how are you approaching your work with this column?

KM: Most of the time I have a vision of a form I want to attempt, or a concept that I develop into a vision inside my head. Every so often I fall in love with a stone and end up doing a direct carve, where I respond to the stone and develop the form as I go. This is one of those stones. I’ve cut the bottom square so I can have it stand here where I can look at it and puzzle out what to do next. I really admire the upward curve, the flare at the top and of course the character of the stone: the dark core surrounded by the swirly rust and gray-brown patina. I know that there are all sorts of possibilities here, playing the richness of a polished surface against the character of the broken stone or a tool marked area that would mostly show white, but give a hint of the darkness of the stone.

This stone could lead anywhere. There’s certainly a suggestion of a torso from mid-thigh on up, if you look at how it moves through here. Or, I could play with the vase shape that the flare at the top suggests. Right now, I think I’ll cut into this profile to mimic the flow of the opposite side, so that there will be a sinuous upwards movement. Once that’s done, I’ll see what to do next. I still haven’t made that first cut. (Note: He’s changed his mind back and forth about four times since the interview.)

SS: Do you often have a preconceived idea of what you want to create?

KM: Sometimes I’ll get a clear vision and look for the stones to use (which I never have in my rock pile, right?). Sometimes the vision will arise from looking at stones or starting to work on them. In any case, the final piece is always changed by the interaction with the stone through the carving process. That’s one of the reasons I like to work with natural stone, rather than quarried stuff. The shapes of the weathered rock set limits, provide a certain awkwardness that keeps me from my impulses to put flowing curves everywhere.

SS: What do you mean by awkwardness?

KM: See this concave surface here? It’s almost the way you might carve it, but it’s clunkier, rougher. So now you have to make a decision whether to develop it into a more free-flowing curve or to use it as part of the form.

SS: What is the balance for you between the conscious/design/intellectual aspect and the unconscious/allowing/discovering aspects of creating?

KM: Assuming we’re trying to make an object that has a presence or power to it, the aspect of ourselves that can deliver that is not the intellectual capacity. It says, “this stone, this proportion, this texture.” The Gestalt of the piece is the Gestalt of your self, the non-verbal. For me, there are a lot of strong, unexpressed feelings that I can’t sort out about a piece. The emotional engagement with the piece changes, particularly for long term pieces, give it a lot of importance: loving it, hating it, finishing it and being melancholy about it being done, wishing it were better... although you can talk about it, there’s a non-verbal essence in what we’re doing. The conscious, intellectual part plays a strong role in analyzing the conceptual basis of the work, of reporting awareness of theme or content, of applying design tools. It’s sort of a game where the conscious and unconscious toss the work back and forth, each contributing to the final sculpture.

SS: Then there’s how the work is experienced by others...

KM: It’s educational seeing how another person thinks about the work. Which can make me realize aspects I hadn’t thought of, even though it was in there in the piece. My piece ‘Twisted Stele’ (stele: “an upright slab carved with symbols

or writing to celebrate the feats of a God, ruler, or warrior”)–“This one has had a hard existence, twisted, pitted, cracked, the central image has disappeared so that we can only guess about its purpose,” Kirk writes in his portfolio. It’s now at Port Angeles Fine Art Center in their “Art on the Town” (a year long show). The Center is a modernist house and grounds overlooking the town. My piece was placed on a grass area near the drive/walkway to the center. They have top-notch shows there. I was pleased to be associated with them. I had originally hoped to get a big chunk of the fine-grained brown Idaho granite (from Mark Heisel). This was his gray fine-grained granite, a 7-foot piece. The brown tone is dirt stains on the surface. It was lying on its side for a year in the studio yard. Occasionally I’d sit on it, lie on it, kick it...

SS: You literally lie on it???

KM: Oh ya, don’t you do that?

SS: Most of my pieces are smaller than that...Do you take naps on it?

KM: No, just lie down, look at the sky. Mostly sit on it. When you have a long stone like that the obvious thing is to stand it upright. So I went with the notion “let’s fight the obvious.” Let’s struggle against it, it could be a boat shaper...

SS: So, you’re mentally going through that process. Originally you have a strong impulse to do something with the stone, like stand it up. Then you say, “that’s too obvious, let’s try this, let’s try that...”

KM: When Mark brought the stone, he said that Linda Heisel saw an Egyptian figure in it. I thought, “that kills that (idea).” Now there’s no way I can see an Egyptian figure.

SS: Ahhh, you’re a contrarian. But, why struggle against your profound preference, often revealed in your first “hit” upon seeing a stone?

KM: Ya, that’s just the way I am. It’s a pain in the ass.. anyway, I looked at the stone and decided it wanted to be upright and at least I went through the process of deciding that. (In his portfolio he states, “The gorgeous natural shape reminded me of both an upright figure and of a menhir, or standing stone erected by the megalithic cultures of western Europe. I tried to work the stone to reveal its internal character without imposing too much of my own vision on it.”)

SS: Kirk, how did you not impose your vision?

KM: By developing the vision through a collaboration with the stone, rather than using it to execute a predetermined design. As I started cleaning it up, knocking some of the rough parts off, it broke off in beautiful conchoidal fractures. I wound up with these lovely concave breaks, which is one of the things I like about granite. I decided to work by hand as much as possible (meaning with a pitching tool). The original shape of the stone had a large protrusion on the upper area. I took about 200 lbs off the original shape. I carved it in by pitching and breaking behind my pitching to break off the tool marks. (Pitching is done by striking the stone near an edge with a large blunt chisel-like tool and heavy hammer, thus removing large chunks of stone.) That area, then, came around to a concave surface. I used pneumatic tools to carve a little “waterfall” in the center to get rid of the final tool marks and then polished that area. Sitting outside, now, for two years it is getting greener and greener, except on the polished surfaces. The polished area originally was subtle, now it’s standing out. That was a change, over time, I hadn’t anticipated. The setting at the art center is a glade, and the relationship of the piece and the space is very nice.

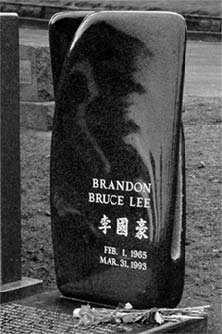

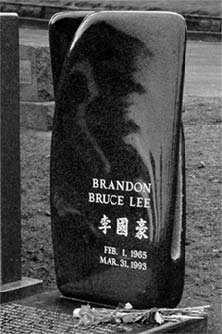

SS: We look at his gravestone /sculpture for Brandon Lee. What was your design process in this?

KM: His mother Linda had seen my slides and liked the symbolism of the split stone in “Cleft” (A split stone with polished interior surfaces, on a sculpted wood base. I visited the site, which is right next to his father’s headstone. She wanted it to be unique, but not to dominate the Bruce Lee marker. So I decided to do a sculpture that read as a standard headstone from a distance. I chose the black granite because it would be impossible to match the existing red granite and the charcoal black would harmonize with the red. Also Brandon had made a point of being his own person, so I wanted to make his marker unique (a rounded slab, black, twisting). I originally designed the two elements of the piece, being separated, then added the helical twist, because it added a dynamism and energy to the form, the two pieces wrapping around each other without touching, joined only at the base. But, in talking to the monument people I realized it would be risky to leave the parts separated.

We were talking about what other people see in your work. In someone’s reaction to our work, we learn more about our own work and thoughts. In this case, a family friend was pointing out that the rough tool marks in the cleft between the highly polished forms is a yin/yang relationship (which I had intended to symbolize the tearing apart of Brandon and his fiancé and his family). Also the shape of the stone is a modified yin/yang form when seen from the top.) If I’d thought about that, I’d have put a bit of polish in the rough tool marks. (Also, the yin/yang symbol is used on the neighboring marker.) The whole thing talks about transformation, life and death. I’m sure that quality is in there, but I wasn’t aware of it until he mentioned it.

SS: Did you go through an initial design discussion, then go off on your own?

KM: I looked at the site, did some drawings, made some clay maquettes to think the design through, then came up with a drawing which I submitted to the client, and she chose. Originally I thought of fabricating it from three pieces. Then I decided to use one piece and carve a cleft between the two elements

SS: How did you work the interior space?

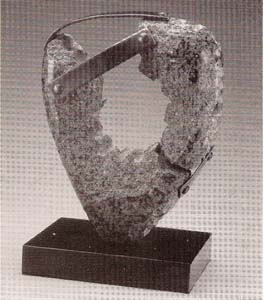

KM: I drilled a sequence of holes and broke out the remaining stone. Then I cleaned up the fins in between (I now know I should have had it cut out by a wire saw) I hadn’t thought through the fact that I could not chisel very deeply because of the tight space. It took me forever. It was nuts. I made extenders for the bushing chisels, then bent a ripper tip at right angles, put an extender on it and scraped the interior surface. I should have simply carved into the side to appear like a cleft. In the end the client was very satisfied that I had taken her ideas and made it work artistically. I was depressed the whole time I did it. His death was such a loss. He was about the same age as my stepsons. Even though the idea was to celebrate his life. We start to talk about “The Forgiving Stone” (a granite river stone which was sliced, fitted, carved, polished and reassembled) as an example of his fitting /constructed pieces.) I think it came out with a lot of energy. This is more of where my thinking is right now, with laminating pieces, the idea of dealing with the space as the sculpture as much as the stone is. I’ll be going back and forth with that.

SS: What other elements are happening in this piece? You have disassembled something, changed it and re-configured the parts. Is that what you’re interested in?

KM: I want to expose the interior of the stone, the character of the interior; the interior in a metaphoric sense. I do want to see the rind, and then the void, the mystery at the center of the rock. Also, energy moving through space, dealing with multiple elements in assembly and carving. You’re exposing the character of the rock, but you’re getting away from the more typical monolith, by taking it apart and putting it back together. I’ve been doing things with ideas about transformation, change, and natural cycles. I’d say the elements of my formal vocabulary involve use of natural stone, the helical upward gesture and the use of multiple, constructed elements. Identifying those as the basis of how I put things together gives me a chance to try something else, or embrace them. Here’s an example of how the conscious analysis of my nonverbal physical efforts brings certain aspects of my work to my awareness, hopefully leading to further exploration by unconscious/haptic/whatever self. Boy, that sounds like BS, but you know what I mean.

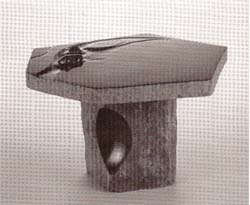

SS: (We’re looking at his “Snag,” a laminated piece made of eight different stones.) Why wouldn’t you have carved that from a single stone?

KM: It’s part of the concept to have multiple elements working together. It is a more efficient way to create a form moving through space, compared to a single stone, there would be a lot material wasted.

SS: How often do you work on your sculpture? How many pieces do you create a year?

KM: My working time really varies. Last year I probably spent about 3-4 months, chunked into April-June and September, and completed two large pieces and two small, which was the most in one year since 1986. I’ve taken up to 4 years to complete a piece (the snake). Some years I have carved very little; on the other hand I ended up working 7 days/week for many months on the Brandon Lee project.

SS: What was your past work experience? And what led you to do sculpture?

KM: I originally trained as a biologist, but while I was a sophomore, I had a chance to study in France for 6 months and became absorbed with Western European art and architecture. When I returned to school in the US, I spent quite a bit of time hanging out with an art student friend and going up to the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco. My senior year I spent finals week out at my friend’s place using his woodcarving tools to create my first sculpture out of a redwood post instead of studying for my finals. I guess I must have been avoiding molecular biology or biochem, since I carved a DNA molecule emerging from the post. I came to Seattle for graduate school in zoology at the UW, mostly for the chance to work at the Friday Harbor Marine Biology laboratories on San Juan Island. After working as a post-doctoral researcher in Biochemistry, and teaching a couple of years as an assistant prof in Biochem and Zoo, I finally woke up to the fact that I was in the wrong business, so I quit. I did vocational counseling to figure out what to do with the rest of my life, and discovered my “secret” love of art and sculpture. I am probably the only person to become a sculptor through vocational counseling. Too bad they never discussed the financial aspects. (laughter) My background in biology explains a lot of my subject matter and form, especially that blasted helix. I ended up studying art at Bellevue Community College and the UW while working in instructional media and design for my day job. Going to Art school was like having a candy store. (SS: Absolutely!) It’s exciting doing art, it’s great. What else would you rather do? I was mostly doing cast and welded metal in school, but then saw a contemporary granite sculpture by Jesus Moroles in Santa Fe in 1982 and wanted to try stone I liked it, A LOT. Hopefully each sculpture leads me into a deeper understanding of what I’m trying to say, or a new direction, and that I’m growing with it. What I’m doing now seems conservative. I feel driven to develop an individualistic approach. What do I do now, given the historic time frame I’m in? I’d like to be a little more wild and crazy, playful; to be less intellectual with it, and see what happens.... “Fun with rocks.’

SS: Let’s talk about your involvement in NWSSA?

KM: I first volunteered to help work on grant proposals to bring in outside money, since I’d had some experience in grant writing in the past. I was asked to run for the Board of Directors, and then to be President for the last two years, so I’ve actually never had the time to do much with finding grants. I’ve been willing to put in the extra work as director and officer because I feel I’ve gained tremendously, both professionally and personally, from belonging to the NWSSA and this was a way to pay back my debt. I’ve certainly gotten to know a lot of my fellow artists through working on the Board. Right now I’m helping our Treasurer, Carmen Chacon, and our past treasurer, Pat Sekor, with getting a finance committee up and running. It’s part of the move to get management details dealt with in committee and have the board concern itself with policy decisions. We’ve been working the last two years on restructuring our management approaches to be a respectable 501(c)3 nonprofit, and wow, has that part been boring. Necessary, though. It’s much more exciting and energizing to talk rocks and art with fellow sculptors, but that’s why somebody’s got to keep the machinery running.

SS: May the wild and crazy live within! Many thanks, Kirk, for sharing here and for all your efforts for NWSSA.

When they sent me a list of questions to prompt my submitting material for an article about myself, the first question was: Who are you? I’ve never thought bio’s to be of enduring interest to anyone but the person they describe—so I’ve contrived shortest sketch possible to show how I fit in our stone sculpture world:

I’m a country boy from the boondocks of northern Ontario, a place that looked really good in the rear-view mirror as I hied off to join the navy at 17. In 1970, now 31, married, kids, salesman, a serendipitous meeting with Toronto sculptor E.B. Cox resulted in an instant obsession for pursuing the life of a sculptor in stone. In a month, I had my own hammer and chisel and was making chips fly under E.B.’s tutelage. Five years and five sellout ‘home’ shows later, still enraptured, I panicked my wife by quitting a high paying day job in sales to move to Vancouver, the only place in Canada where you can sculpt outdoors year ‘round. I was certain I could make a living as a sculptor. It was not because I was your world’s great artist (I never did get to be so) but I had three compensatory attributes: I was never satisfied with the last sculpture I had created; I had an innate understanding of tools; most importantly, I could sell.

By 1983, a series of successful ‘home’ shows resulted in a stable of George Pratt collectors beginning to form; the phone was ringing somewhat regularly and while income was never assured, it was becoming adequate. When a strapping gal named Meg Pettibone trekked up to Vancouver to seek help in forming a guild of sculptors in stone, I bought in to the notion and along with a small group of other sculptural aspirants, we established the NWSSA. Twenty-five years onward, I have had uncounted successful shows, been commissioned to produce presentation sculptures for many world leaders, and have authored seven major public artworks.

I’ve carved (or tried to) every type of stone, emerging in my senior years as primarily a granite carver. I still like to work and produce but my ego has had all the stroking it needs. I still think of myself as being only a moderately good artist who gets it right now and again. I put what I can back into the profession that has been so very good to me by instructing others. (Instruction has its own payback; every year at our symposia, I am afforded the profound pleasure of meeting aspiring sculptors whose talent far outstrips mine. Dang, if only they could sell.)

And that about sums me up. Now, to the important stuff. In a thirty-nine-year career I’ve touched upon countless others in the stone arts. I’ve listened and watched and made every experience a lesson. Here are a few vignettes that for me have been formative.

Wisdom From My Old Mentor: E.B. Cox

This advice from my irascible, curmudgeonly and talented mentor still sticks with me.

Nowadays they go out of their way to make art that is—well—odd. It seems not to be so possessed of artistic merit as just—oddness. Don’t be fooled by it, boy. Don’t do odd.

A stone sculpture should reflect the attributes of stone: Think mass; think strength. Stone is not the stuff of thin birds’ wings and angels’ fingers. It is the stuff of bears and whales; it is the stuff of torsos—males with brawny shoulders, females with strong hips.

If you want to carve alluring females boy, stop messing about with playboy breasts; look to the neck and shoulders, boy; look to lusty hips. Those breasts you’ve hammered out are for truck-drivers.

Don’t be seduced into carving every colored stone you see; colored stones, shiny finishes, they’re cute but they lack the most important feature of sculpture: shadow and mood. Go for the plain stones, boy. What’s locked up in colored stones is glitz; what’s locked up in limestone and granite and white marble is elegance.

Encounters That Influenced My Career

Meeting Meg Pettibone in 1984. It was she who conceived of the notion of a guild of sculptors in stone that became the NWSSA and who inveigled me into helping get it started.

Meeting Rich Beyer at the first meeting. It was from him I learned that sculpture could be light-hearted and rustic and that the best sculptures tell a story. (Take a look at Rich’s vignette in Fremont, ‘Waiting for the Interurban’. It’s located at Fremont Ave. N and N 34th St.) When Rich’s principles as a Quaker would not allow him to sculpt a portrayal of Eskimos bearing weapons for the Alaska Veterans Memorial, he recommended me for the job; thus I acquired my first major sculpture in granite.

Working in the same space as other creative people, in particular stone sculptors (hence, the value of attending as many symposia as one can), I’ve shared workspace with E.B. Cox, Michael Binkley, Dave Fushtey and Sandra Bilawich (the latter three being early NWSSA members.) I do not copy them, but I have been abundantly inspired by them and influenced by them in a way that I would not be if they were but casual sculptor acquaintances. It is by day in-day out being close enough to watch the way they apply their skill, to observe their thought processes in working through thorny technical problems, to be delighted (or otherwise) by a line or form developing in their current project and subliminally emulating it in one’s own work. Invaluable.

Influences/landmark Events/philosophies That Have Been Formative To Me

Work Hard And Often

Contrary to what one may think, when we unceasingly create sculpture, we don’t get hackneyed Ideas and skills flow exponentially with the rate of production. In working ourselves to exhaustion, we just get better.

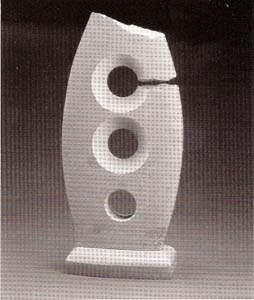

‘Coffee-table’ Sculptures

I develped the method for producing ‘coffee-table’ sculptures outside the Eskimo soapstone realm by working hard stones on a stationary grinder. Such sculptures were just not done by anybody when I discovered the silicon carbide grinding wheel and carbide cloth disc in 1971. It was by being able to produce, in relatively short time, neat little sculptures in stones other than soapstone, which apparently charmed people and could be sold for an affordable price, that I was able to make a living.

The tools for grinding have evolved from those primitive carbide wheels to specially formulated diamond discs (and much more) now, but the grind/cut/polish method remains the same. Above all else, this phenomenon of producing the ‘coffee-table sculpture’ will provide the ability to carry on as a sculptor, for it assures one’s solvency while struggling to attract commissions for greater works that will inevitably follow.

High, Gleaming Polish On Jade

When trying to unlock the secretsof polishing jade, the process defeated me, I resignedly walked the ten blocks to the studio of jade sculptor Lyle Sopel, who at the time, was struggling in his sculptural niche as was I in mine, and humbly asked him to show me how. I am grateful that this he very patiently did.

I haven’t done a lot of jade sculptures over the years but those I’ve done have all found great favor and whatever excellence may be in them is the result of that fortuitous hour of instruction from Lyle.

(See his website: www.sopel.com)

Attending Symposia

There is nothing, absolutely nothing, so valuable to a stone sculptor as to be immersed in an environment of others of like mind, all making the chips fly. I cannot place a value on the experience of being exposed to the works of others as they were being carved, works that I wish I had done: Tracy Powell’s ‘Little Man With a Horn’; Tamara Buchanan’s ‘Man In a Coat’; Dorbe Holden’s ‘Female Figure’; the basalts of Rich Hestekind; the finishing textures of Stuart Jacobsen; the contextual excellence of in the wonderful (and difficult) sculpture John Hoge (remember him?) did for the Polytechnical Institute. These and a couple of dozen more (sorry if I didn’t name you) have made deposits into my mental bank account that have paid uncounted interest over the years. Every sculpture I have carved has been partially financed by making a withdrawal from the account; yet the principal does not deplete because each year as I attend a symposium, the account is replenished.

Finding Deep Pockets

I discovered the importance of ingratiating myself to persons in the interior design and corporate community in building a source of sales. It is this group of people who can recommend our work to the people among us with the deepest pockets. Related people of influence, but no less important, have been the individuals whose responsibility is to acquire corporate gifts. Building a reputation among this group has generated uncountable sales of ‘corporate presentation sculptures’ over the years - and the recipients of such gifts have in turn very often made contact and begun acquiring presentation gifts for their own purposes. It has been a very rich source of sales.

My Photos

I have literally hundreds of images of works large and small, traditional and contemporary, importantly commissioned and tossed off casually. I purposely chose the pictures shown for two reasons: They reflect what E.B. Cox advised me about plain stones and shadow and mood; and I thought it might be interesting to show works that an old NWSSA member did years before many of those who will attend the 2009 Symposium were born. In the same spirit, I know these feature articles like to show a picture of the sculptor. I picked over the many I have, both complimentary and otherwise, and decided there were none better or more fitting than a pencil sketch done some years back by everybody’s favorite member, darling Nancy Green.